Editorial note to readers

A version of this study was originally published on June 10. We previously used the term “racial conspiracy theories” as an editorial shorthand to describe a complex and mixed set of findings. By using these words, our reporting distorted rather than clarified the point of the study. Changes to this version include: an updated headline, new “explainer” paragraphs, some additional context and direct quotes from focus group participants.

Claudia Deane, Mark Hugo Lopez and Neha Sahgal contributed to the revision of this report.

How we did this

Pew Research Center conducted this study to explore how Black Americans think about the factors that contribute to or hinder their success in the United States. An early 2024 report explored the success factors, and this current report focuses on the hindrances. Based on their real personal and collective historical experiences with racial discrimination, Black Americans might be suspicious of the actions of U.S. institutions.

These suspicions often circulate in Black spaces as ideas about the intentional or negligent harm that hinders Black people from thriving. For this report, Black adults were asked in a survey how familiar they are with these ideas. Then, regardless of their familiarity, they were asked if they thought these things were restricted to the past or could also be happening today. Detailed examples of these ideas and corresponding survey results are discussed at length in Chapters 2-7.

We surveyed 4,736 U.S. adults who identify as Black and non-Hispanic, multiracial Black and non-Hispanic, or Black and Hispanic. The survey was conducted from Sept. 12 to 24, 2023, and includes 1,755 Black adults on the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP) and 2,981 Black adults on Ipsos’ KnowledgePanel.

Respondents on both panels are recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. Recruiting panelists by mail ensures that nearly all U.S. Black adults have a chance of selection. This gives us confidence that any sample can represent the whole population (see our Methods 101 explainer on random sampling). For more information on this survey, refer to its methodology and topline questionnaire.

This study also included seven focus groups with Black adults of various ages, income levels, political affiliations, and geographic locations. Conducted online from May 23 to June 1, 2023, these groups gave Black adults the opportunity to describe how they defined success and accounted for hindrances to their success. For more information, read the focus group methodology.

Terminology

The terms Black Americans, Black adults and Black people are used interchangeably throughout this report to refer to U.S. adults who self-identify as Black, either alone or in combination with other races or Hispanic identity.

Throughout this report, Black non-Hispanic respondents are those who identify as single-race Black and say they have no Hispanic background. Black Hispanic respondents are those who identify as Black and say they have a Hispanic background. We use the terms Black Hispanic and Hispanic Black interchangeably. Multiracial respondents are those who indicate two or more racial backgrounds (one of which is Black) and say they are not Hispanic.

In this report, immigrant refers to persons born outside of the 50 U.S. states or the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories.

To create the upper-, middle- and lower-income tiers, respondents’ 2021 family incomes were adjusted for differences in purchasing power by geographic region and household size. Respondents were then placed into income tiers: Middle income is defined as two-thirds to double the median annual income for the entire survey sample. Lower income falls below that range, and upper income lies above it.

Throughout this report, Black adults with upper incomes are those who have family incomes in the upper-income tier. Black adults with middle incomes and Black adults with lower incomes have family incomes in the middle- and lower-income tier, respectively. For more information about how the income tiers were created, read the methodology.

Throughout this report, Democrats are respondents who identify politically with the Democratic Party or those who are independent or identify with some other party but lean toward the Democratic Party. Similarly, Republicans are those who identify politically with the Republican Party and those who are independent or identify with some other party but lean toward the Republican Party.

While many Black Americans view themselves as at least somewhat successful and are optimistic about their financial future, previous work by Pew Research Center also finds most believe U.S. institutions fall short when it comes to treating Black people fairly.

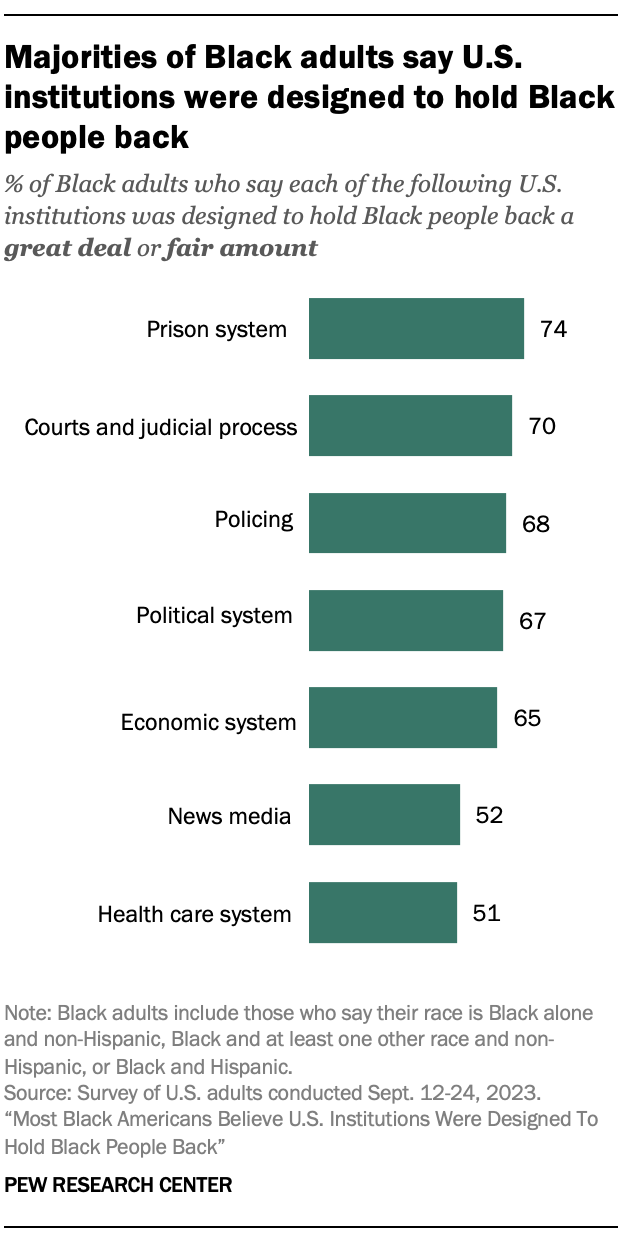

A new analysis suggests that many Black Americans believe the racial bias in U.S. institutions is not merely a matter of passive negligence; it is the result of intentional design. Specifically, large majorities describe the prison (74%), political (67%) and economic (65%) systems in the U.S., among others, as having been designed to hold Black people back, either a great deal or a fair amount.

Black Americans’ mistrust of U.S. institutions is informed by history, from slavery to the implementation of Jim Crow laws in the South, to the rise of mass incarceration and more.

Several studies show that racial disparities in income, wealth, education, imprisonment and health outcomes persist to this day.

The goal of the current study is to explore how Black Americans think about U.S. institutions and the impact they have on their success.

Specifically, we examine the extent to which Black Americans believe U.S. institutions intentionally or negligently harm Black people and how personal experiences of racial discrimination factor into these beliefs.

The beliefs and narratives that Black Americans have about institutional harm have long been studied by scholars in the health and social sciences and the humanities. Narratives about how institutions were designed to hold Black people back also surfaced in several of the online focus groups Pew Research Center conducted with this study last year. (Selected quotes from our focus group discussions can be found in an accompanying text box.)

To measure the prevalence of these narratives of mistrust, we conducted a survey of 4,736 Black adults in the U.S. from Sept. 12 to 24, 2023.

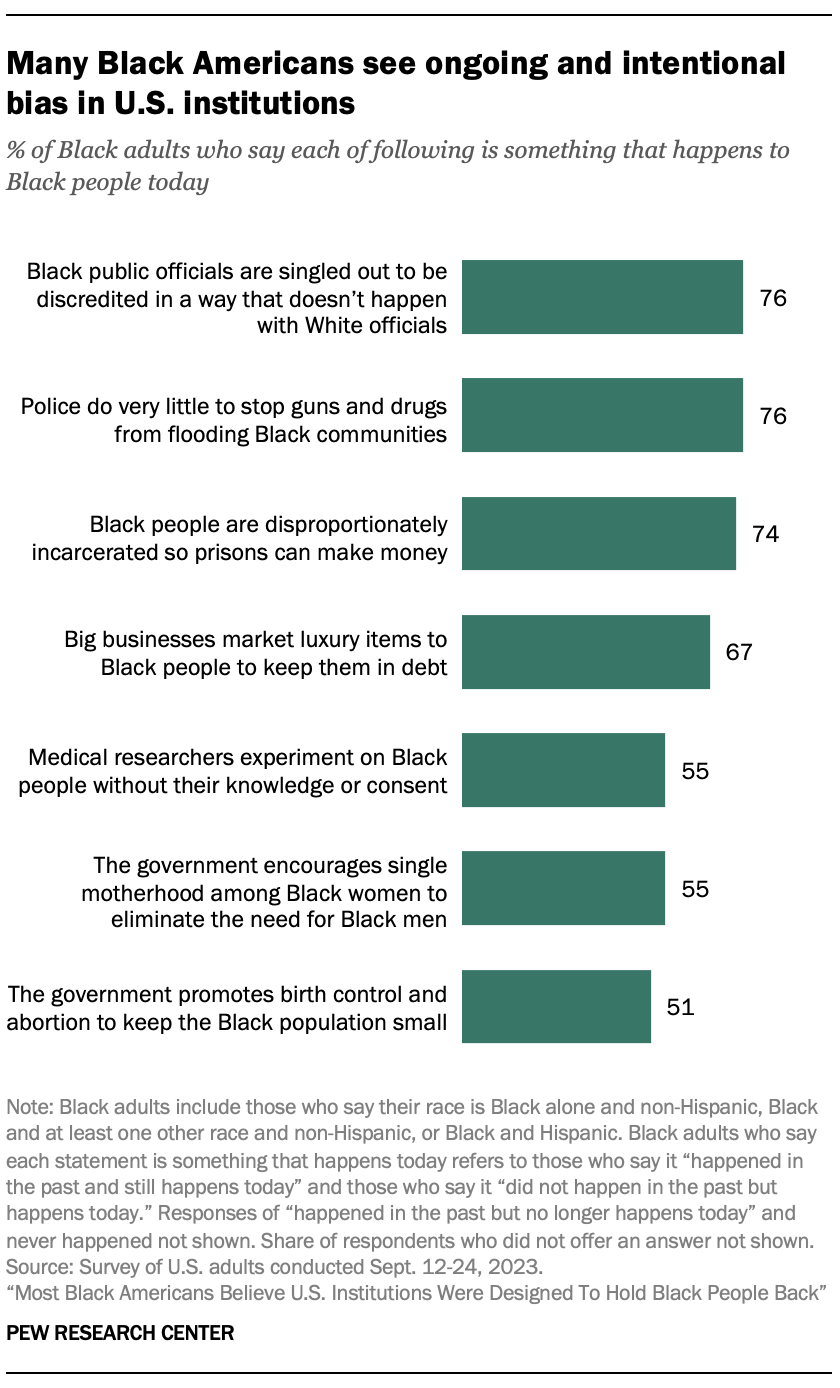

First, respondents were asked if they had ever heard a series of statements about how U.S. institutions might intentionally or negligently harm Black people. Respondents were then asked if they thought these harms were also happening to Black people today. Here are some key findings about Black Americans’ beliefs in institutional mistrust.

The report also finds that Black Americans who have experienced racial discrimination are more likely to believe U.S. institutions intentionally or negligently harm Black people.

There are also modest differences among Black Americans by gender, education, family income and political affiliation. Still, majorities across many Black demographic subgroups are familiar with these statements about the intentions of many U.S. institutions and say these things are happening to Black people today.

In their own words: Quotes from our 2023 focus groups of Black Americans

To understand how Black Americans view success and setbacks in the U.S., in May and June 2023, we conducted seven online focus groups nationally among Black people of varying income, age and ideological backgrounds. For details on how groups were defined and recruited, refer to the focus group methodology.

One theme that emerged: Some participants felt they are up against a system deliberately designed to hold them back. The following are some illustrative quotes:

“I believe there are … strategic works, behind the scenes, that are being done to sabotage a Black person’s effort. … You could be on the road to success with nothing stopping you. But then, all it takes is one incident that was planned and plotted against you to destroy your life.”

– Woman, low-income group, early 50s

“As Black people we are always fighting some type of fight. … We always get to some type of height of success. And then there’s always something that takes us down. …There is always something in the way.”

– Woman, young adult group, late 20s

“Well, there’s institutionalized stuff that is invisible. …There are institutionalized things that are in place that one has always suspected, but because they are seemingly benign, you can’t really call them out on it. …There are things like that which I think are purposely built into society or industries or whatever to keep certain numbers down because of access to financial gain.”

– Man, high-income group, late 30s

“I trust the government to an extent, but when it comes to certain things, I don’t. For example, take the pandemic. They had all this help out there for people, but there were certain people that applied for help that just couldn’t get it and they were literally just struggling to just get by. … I feel like us Black people are helped the least because we’ve always had the short end of the stick.”

– Woman, Republican group, late 20s

“This is a capitalistic society. And I feel as though Black men just have to be the ones at the bottom in order for this system to succeed. … I think that a few hands may be part of this. I don’t want to speculate, but it just still seems to be a system set in place where Black people, especially Black men, have not been successful for a while. We can even go back to Black Wall Street where we were starting to have a little bit of success, and then that was taken down by the powers to be. So whatever system it is, it’s a pretty good system that doesn’t reveal itself so easily.”

– Man, Republican group, late 30s