I recently stood in the doorway of the Foster Auditorium on the campus of the University of Alabama. On June 11, 1963, Gov. George Wallace stood in that very spot and blocked access to Vivian Malone and James Hood, two newly admitted students. They were Black.

Wallace only stepped aside after President Lyndon Johnson nationalized the Alabama National Guard and its commanding officer reluctantly ordered his governor to do so. Then-Deputy United States Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach escorted the students through the doorway to opportunity in America.

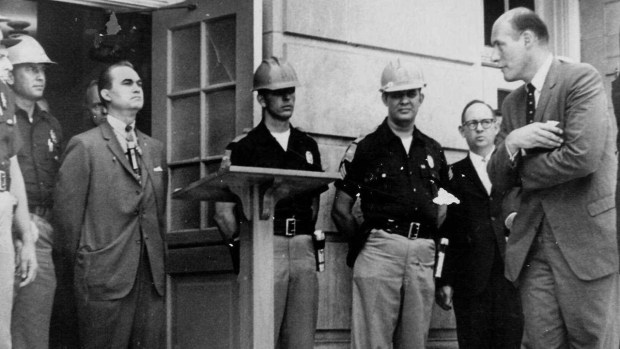

Associated Press

Alabama Gov. George Wallace is shown making his “stand in the schoolhouse door” on June 11, 1963, to prevent two black students, Vivian Malone Jones and James Hood, from registering at the University of Alabama.

Last week, six members of the United States Supreme Court took their places in the schoolhouse door. They colored their decision with what they described as a “colorblind” veil. I am not fooled.

The throughline that becomes so apparent as you learn the lessons of Alabama in the 1960’s is that racism as public policy can adjust as rules and limits are set. When the formerly enslaved became full citizens in the aftermath of the war between the states, after the short-lived period euphemistically referred to as “reconstruction”, white political leaders and judges found a variety of workarounds to continue to deny blacks the right to vote, not to mention the allegedly unalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Can you guess the number of jellybeans in a large jar? Or, in the alternative, can you pass a 20-page questionnaire on the United States Constitution? That was the right of passage to suffrage for more than a few Black Americans. Before the Selma to Montgomery March in 1965, 51% of Selma’s citizens were African American yet only 1% of registered voters were Black.

Dave Martin/AP

Thousands of demonstrators, led by Georgia Congressman John Lewis, Jesse Jackson, and other civil rights leaders march across the Edmund Pattus Bridge in Selma on March 4, 1990. It marks the 25th anniversary of the original Selma to Montgomery march in 1965.

I encourage every reader to visit the Civil Rights Trail in Alabama as I just did with my husband, David, and 15-year-old son Cole. If you retrace the steps of the Rev. Martin Luther King and the tens of thousands of civil rights heroes, if you visit the Legacy Museum in Montgomery, if you walk across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, if you stand in the sanctuary of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, if you stop for a moment at the monument to Viola Liuzzo (Google that name) you might begin to understand the wrong that affirmative action seeks to right.

Kevin Glackmeyer/AP

U.S. Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga., center, talks with those gathered on the historic Edmund Pettus Bridge in 2012 during the 19th annual reenactment of the “Bloody Sunday” Selma to Montgomery civil rights march.

Since 1995 I’ve been employed at a university that takes pride in its commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion. I now teach a course that helps our incoming students recognize prejudice, i.e. judging people based on aspects of their own identity that they did not choose. In Florida and a growing number of states these DEI initiatives are not just ignored, but they are outlawed explicitly. The Supreme Court’s two affirmative action decisions only serve to enable this racist tendency.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson made the point clear enough: “…to say that anyone is now victimized if a college considered whether that legacy of discrimination has unequally advantaged its applicants fails to acknowledge the well-documented ‘intergenerational transmission of inequality’ that still plagues our citizenry.”

Divided Supreme Court outlaws affirmative action in college admissions, says race can’t be used

I’ve spent the better part of four decades trying to understand our state’s criminal justice system where today 71% of those incarcerated are either Black or brown. There is no question that admission to American prisons and jails disproportionately favors persons of color. Is this too a violation of the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection? I would welcome that discussion. The full name of Bryan Stevenson’s inspired museum is “The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration.” That’s our nation’s history. That too is our call to action.

Going forward, we must endeavor to abide Dr. King’s exhortation: that “this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed.” At the conclusion of the March from Selma, on the steps of the Alabama State Capitol he proclaimed: “How long? Not long.” I’m growing impatient.

Mike Lawlor is an associate professor of criminal justice at the University of New Haven.