The Supreme Court’s affirmative action ruling will have far-reaching consequences for Black and Latino students hoping to attend medical school and, in turn, only worsen the health disparities among people of color across the country, experts said.

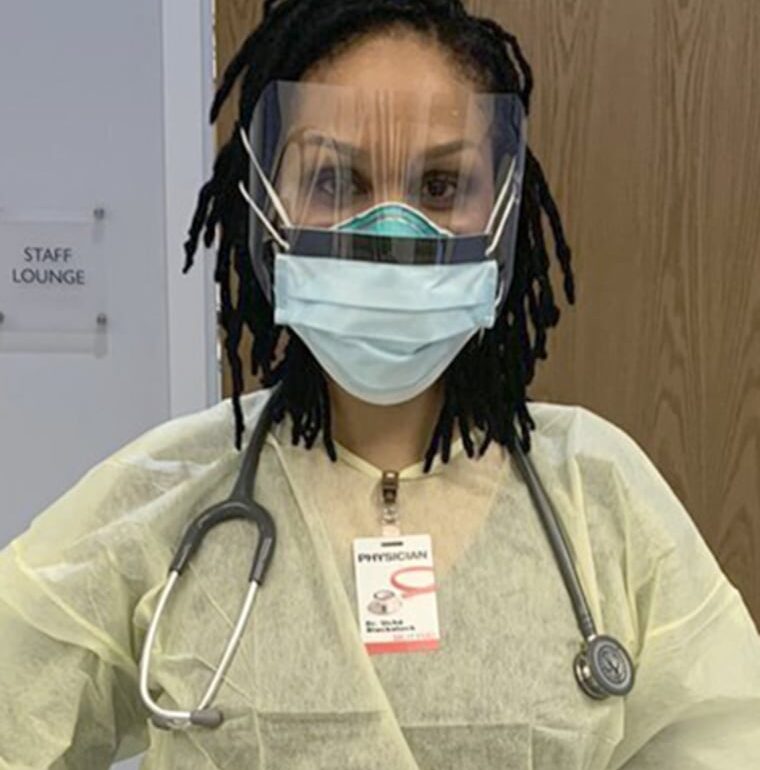

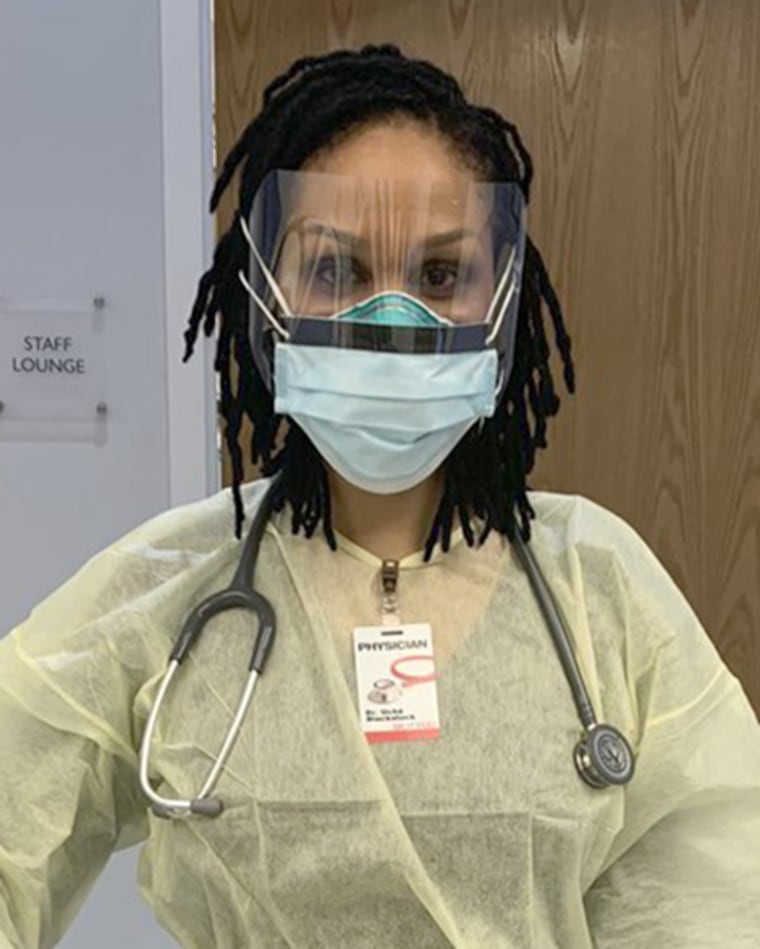

After the high court’s ruling Thursday struck down affirmative action programs at the University of North Carolina and Harvard, many fear that medical and nursing schools and other professional institutions will no longer be able to foster diversity by considering race in their admissions processes. The decision will result in fewer Black physicians and more racial bias in the medical field, said Dr. Uché Blackstock, a physician who is the founder of Advancing Health Equity.

“Fewer Black health professionals means less culturally responsive and equitable care for Black patients,” she said. “Also, the lack of Black representation among Black health professionals is a problem for younger generations since ‘you can’t be what you can’t see.’”

Blackstock laid it out in stark terms in a string of tweets. “This is about life & death for us. Today, we are only 5% of physicians,” she wrote. “This decision will hasten the deaths of Black people in this country and we already die prematurely.”

The court ruled that affirmative action programs violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution and are therefore unlawful. The vote was 6-3 in the UNC case and 6-2 in the Harvard case, major victories for conservative activists. Although the ruling bars schools from using race as a factor in admissions, prospective students can still share their racial or ethnic backgrounds through application materials like essays and personal statements and through their extracurricular activities.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor highlighted the ruling’s potential impact on health care, writing in her dissenting opinion that “increasing the number of students from underrepresented backgrounds who join ‘the ranks of medical professionals’ improves ‘healthcare access and health outcomes in medically underserved communities.’”

Data and decades of research support Sotomayor’s opinion. Black and Latino people are both more likely to have chronic and life-threatening health conditions and to lack health insurance as a result of systemic racism, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. However, research has shown that those health outcomes for Black and Latino patients are better when they are treated by doctors who share their race or ethnicity.

Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra highlighted the disparities in his response to the ruling.

“This ruling will make it even more difficult for the nation’s colleges and universities to help create future health experts and workers that reflect the diversity of our great nation. The health and wellbeing of Americans will suffer as a result,” he said.

Dr. Jesse M. Ehrenfeld, the president of the American Medical Association, echoed Becerra.

“Diversity is vital to health care, and this court ruling deals a serious blow to our goal of increasing medical career opportunities for historically marginalized and minoritized people,” he said in a statement. “This ruling is bad for health care, bad for medicine, and undermines the health of our nation.”

Black and Latino admittance to medical schools has improved in recent years, with Black students making up 10% of matriculants in the 2022-23 school years and Latino, Hispanic or Spanish-origin students making up 12% of total matriculants, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Although that is an improvement, Black and Latino students still represent a small proportion of the overwhelmingly white medical school student bodies.

As of 2019, 54.6% of all medical students in the country’s medical schools were white, and Black and Latino students accounted for 11.5%, according to the most recent overall data from the Association of American Medical Colleges.

More schools are making efforts to bridge the racial gap in medical schools. The Association of American Medical Colleges established the Action Collaborative for Black Men in Medicine network to support Black men interested in medicine. Xavier University in Louisiana and Morgan State University in Maryland, both historically Black universities, recently announced they are establishing medical schools.

“We need more Black physicians and more Latino physicians, because being a doctor is a form of opportunity for individuals and we should all have the same access to opportunities to fulfill whatever our potential is,” said Dr. Max Jordan Nguemeni, a resident physician of internal medicine at Harvard Medical School’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital. He also writes about racism in the medical field.

“I hope that medical schools are really prepared to find other ways to ensure and fulfill their mission of a more diverse medical school student body and a more diverse pipeline.”