Civil rights for African Americans have been a struggle in many parts of the nation, including Bloomington-Normal. But the first Black city council political candidate in Bloomington came 16 years before women gained the right to vote in Illinois.

That first African American candidate was a veteran, activist, member of a literary society, doorman at the state capital, and barber.

“Richard Blue’s remarkable life really speaks to the travails and the triumphs of black Americans in the 19th and 20th centuries, the limitations they faced socially, politically, economically, and yet the ability not only to navigate this unjust world they faced, but to succeed and fight for dignity,” said Bill Kemp, librarian and archivist at the McLean County Museum of History.

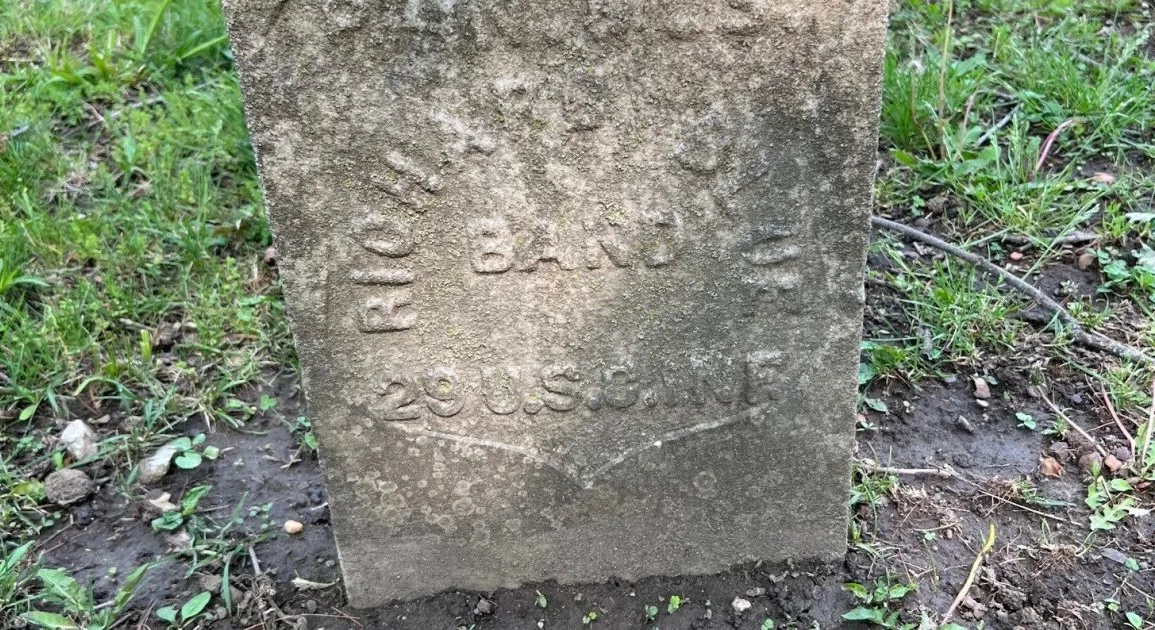

Blue was born in the 1840s in Dayton, Ohio. His parentage is not known, but his childhood came as part of the family of judge James Rayburn, a prominent white family in the Dayton area. The Rayburns settled in McLean County in the early 1850s in Old Town Township, just east of Bloomington. Richard Blue was 9 years old and listed as an African American farm laborer for the family. During the Civil War, Blue enlisted in the 29th U.S. Colored Infantry. Blue was one of 180,000 Black men to serve in the Union Army during the Civil War. There are at least 39 Black men from McLean County known to have served in the war; 13 gave their lives in the struggle.

“Because he had sustained a foot injury on the farm, he was assigned to be a musician for the regiment, and he became the principal musician,” said Kemp.

At the war’s end, the unit had garrison duty in Texas.

“This was just absolutely miserable. A relatively hostile population still, albeit after the war. Hot and humid, soldiers suffered from malaria and other camp borne ailments,” said Kemp.

The regiment had a view of a historic moment, though. In Galveston, Texas, on June 19, 1865, General Gordon Granger issued General Order #3. It announced what was known in much of the rest of the nation — that all slaves were free.

“We celebrate this declaration as Juneteenth day today, and we presume Richard Blue was there in Galveston,” said Kemp.

By 1866, Blue had separated from the Rayburn family, and had become a barber. He spent his entire adult life living in the 300 block of South Madison Street just south of downtown Bloomington, near where the warehouse district begins. He married Emily Cooper in 1870. They had six children. Three lived to adulthood.

“Black Americans faced just enormous restrictions when it came to occupations locally until the 1950s and 1960s. For example, Black men were denied that ticket to a middle class that a lot of immigrant white men were to work at the Chicago and Alton Railroad shops,” said Kemp.

There were six Black men working as barbers in Bloomington. By the mid-1870s, there were Black barbers in small towns outside of Bloomington-Normal such as Leroy, Saybrook, and Lexington, even though they were not allowed to live in some of those communities at the time. Barbershops were segregated, so they were cutting white hair.

“Richard Blue had to supplement his income elsewhere. He was a door attendant or popular Butler at at-large private parties held by upper middle-class whites in the area,” said Kemp.

With the 1868 passage of the 14th Amendment, which conferred citizenship on all residents born in the United States, Black Americans gained full citizenship. In 1870, Blue became the first Black resident of Bloomington to serve on a local jury.

“The case is an interesting one. It’s Bloomington vs. Bateman. That’s H. N. Bateman who had two restaurants in downtown Bloomington,” said Kemp. “The issue was Sunday or blue laws, which were meant to tamp down commercial activity on Sundays. That was the Lord’s Day. Restaurants were supposed to be closed. Theaters were supposed to be closed. Bateman evidently, was selling, on the sly, ice cream and glasses of lemonade. Richard Blue, was on that jury trial.”

Running for Bloomington Council

Blue also was active in local, state, and national Republican politics. For decades after the Civil War, Black Americans primarily aligned themselves with the Republican Party — the party of Abraham Lincoln, the party of emancipation, the party that saw the Civil War to its end.

“Republicans were the party that stood for a modicum of Black civil and political rights during the Reconstruction Era. Black residents in Bloomington were aligned with the Republican party until the Great Depression, or even a little bit afterwards,” said Kemp.

Blue attended both general and segregated Republican conventions in Illinois and locally. In 1879, there was some unrest in the Black community to share in the political benefits of the party.

“‘The time has now arrived,’ said Gus Hill, another Black leader, ‘when the colored people should rise and demand office from the hands of the Republican Party.’ They wanted a share of the offices because they had been loyal supporters of the Republican Party. Richard Blue was nominated for the office of alderman in the third ward. The Pantagraph did not endorse him, but did acknowledge that Richard Blue ‘had a good education and practical experience and would no doubt if elected, serve the people of his ward with credit,'” said Kemp.

William W. Stevenson ran away with the election and the city had to wait a full century until a Black resident would be elected to the Bloomington City Council. In 1979, Eva Jones became that council member.

As a loyal Republican, Blue did get some patronage jobs from time to time. He was a mail carrier in 1879. In 1884, he was appointed oil inspector of the city of Bloomington. For more than two decades, he periodically served as doorkeeper at the Springfield State Capitol.

“He also had an interest in political and civil rights,” said Kemp. “He was a member of the Afro American League, a national organization. It had a local chapter, and he was one of the leaders. The League fought racial terror and brought up the issue of lynching in the deep south. Blue was involved in that and in educating people in the North about what was happening.”

He died in 1921.

“The Pantagraph newspaper noted that he was ‘one of Bloomington oldest and most highly respected’ citizens.’ The Bloomington Bulletin, a Democratic paper, noted admiringly that Richard Blue was a staunch and influential Republican,” said Kemp.

Richard Blue will be a character in this year’s Evergreen Cemetery Walk on Sept. 30, and Oct. 1,7, and 8. Advance ticket sales begin Sept. 5.

The series McHistory is a co-production of WGLT and the McLean County Museum of History.

We depend on your support to keep telling stories like this one. You – together with donors across the NPR Network – create a more informed public. Fact by fact, story by story. Please take a moment to donate now and fund the local news our community needs. Your support truly makes a difference.