Visual artist John Halaka came into a greater awareness of civil and human rights as a college student in the 1970s, and that desire to learn about and amplify the varied histories and experiences of others has only expanded over the years. That expansion can be seen in his latest exhibition, “Listening to the Unheard/Drawing the Unseen: Meditations on Presence and Absence in Native Lands,” focused on the stories of Native American, Black, and Palestinian people.

“I wanted to figure out a way to place the experience of Palestinians in this broader anti-colonial discourse, this broader history of resisting colonization, imperialism. One of the ways to do that — and I’m not inventing this in any way, there are a lot of others who have done this — is to talk about the similarities in terms of the anti-colonial struggle,” he says, noting that his own Palestinian ancestry has been part of what motivates his work. “This history of erasure that was experienced by a whole lot of people across the planet. Residing here in America, and being influenced by the American Indian Movement, the Civil Rights Movement, I wanted to learn more about that and there are definitely heroes within those movements.”

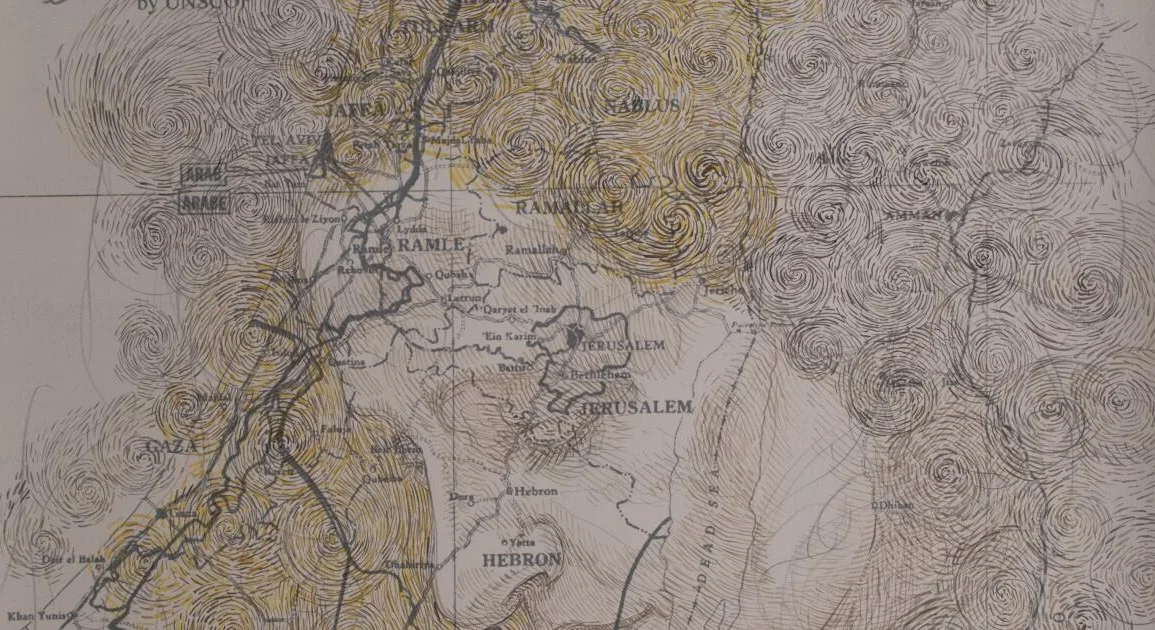

The drawings — on display at the Oceanside Museum of Art through Feb. 18, 2024, with a celebration event on Nov. 18 —are taken from the artist’s “Landscapes of Resistance” and “Forgotten Survivors” series, featuring drawings on maps of the United States and Palestine and narratives of dispossession, reclamation, and resistance.

Halaka was born in Egypt to Palestinian and Lebanese parents before his family immigrated to the U.S. when he was 12. He is a professor of visual art at the University of San Diego. His work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, and he’s won numerous grants and awards (including a Fulbright fellowship in 2011 to document the stories of Palestinian refugees living in Lebanon). He took some time to talk about his latest exhibition and why he finds it critical to listen, to see, and to learn about these histories of erasure. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity. )

Q: What led you to focus on these experiences of displacement and survival in “Listening to the Unheard/Drawing the Unseen”?

A: It definitely started a bunch of years ago with focusing on the rights of Palestinians, the rights of an indigenous population that was forcibly displaced from their land, that has, in many ways, been sort of erased from history. In 1982, I remember going to the library and looking at every dictionary and the word “Palestine” only referenced the historical land, there was nothing in there for Palestinians, so they had literally been erased from our discourse in the West. Being a person who’s interested in civil rights and human rights, I felt like I needed to begin to focus on that. In part, yes, my history as a descendant of Palestinians had something to do with that, but it was really kind of a deep interest in the rights of human beings, the people that I was most familiar with.

There was also a strong influence when I was a college student in the ‘70s in New York. I started to become aware of the Civil Rights Movement. It’s not like it was new in the world, but it was sort of new to me, these rights of people fighting to be seen as human beings, to be treated as equals, to have a place in society without being forced to constantly compromise or justify their existence. At the same time, I started to become aware of the American Indian Movement, AIM, and the Native folks that began to address the history of erasure that they have experienced over multiple generations. The history of denial of their humanity. Those were pivotal influences on me in the ‘70s. Later on, in the ‘80s, as I began to address and make work that explored ideas of justice, I began to focus on the rights of Palestinians because that was the topic that I felt closest to, most interested in, and began to spend a whole lot of time researching it, reading, listening to people, and reading some more and becoming familiar with both the capital “H” history and the lowercase “h” history. What I mean by that is the history of individual men and women who experience dispossession, who experience displacement, who experience a sense of being rendered unseen in a world where we can easily be forgotten. That began in 2004 or 2005 when I took my first trip to Palestine. Before that, it was all reading about it. Then, having conversations with people in Gaza, having conversations with people in the West Bank, having conversations with internally displaced Palestinians who became citizens of Israel and learning things that books never fully, clearly, or eloquently conveyed. I spent from that time on going back and beginning to record the stories of these individuals. Not that the books were in any way bad, I’m not saying that, but compared to the stories of these folks — in many cases men and women who never went to school, they spent their lives as laborers, as farmers, a whole bunch of them in refugee camps in extremely rough conditions — they were able to convey their personal and their families’ experiences, which I found tremendously moving. So, yes, for me, it started with an interest in the rights of individuals, civil rights, American Indian rights, and the rights of Palestinians as a displaced population that I was most familiar with and most connected to.

Q: And do you mind briefly sharing a bit about your personal connection to the Palestinian refugees and that experience?

A: I was born in Egypt. My father’s family is Palestinian; my mother’s family is Lebanese. We grew up as Arabs in Egypt, so you blend in. Both sides of my family are working-class, middle-class families. My dad worked in a bank, my mom was a seamstress and made dresses at home on our dining room table. We were very much a working-class family, but they were completely apolitical. They didn’t talk about politics. Occasionally, when uncles would visit, they would have conversations about politics, but I didn’t grow up in a household where we discussed politics. There are a whole lot of reasons for that, and I don’t want to go into it now, but I didn’t grow up with an emotional kind of connection to Palestine. I knew my father’s family was Palestinian, I knew my mama’s family was Lebanese, and we heard good things, but we didn’t really grow up knowing about the history of displacement, which is really odd, right? My father’s family is not a refugee family; my grandfather moved to Egypt before Israel was established by probably three decades. He died as a relatively young person in the early ‘30s, so I don’t know his story. He moved to Egypt, probably in the early 20th century, maybe just when the British settled into Palestine at the end of World War I and kind of took over the administration of Palestine after the Ottoman Empire was sort of dismantled at the end of World War I. I think that’s the period when my grandfather moved from Palestine to Egypt. His brothers stayed in Palestine, so there’s still a branch in Palestine. So, there is the historical connection, but it’s really the political connection that I came to when I was coming of age as a college student.

Q: Some of the pieces are taken from “Landscapes of Resistance,” a series honoring the work of Native American, Black, and Palestinian artists, activists, and scholars, including images of Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, Mary Brave Bird, and Leonard CrowDog. Can you talk a bit about what you learned during your research process of a couple of these individuals, and how that informed the resulting images of them that we’ll see in this exhibit?

A: There were a lot of things that brought this project about. One of those things was that I wanted to figure out a way to place the experience of Palestinians in this broader anti-colonial discourse, this broader history of resisting colonization, imperialism. One of the ways to do that — and I’m not inventing this in any way, there are a lot of others who have done this — is to talk about the similarities in terms of the anti-colonial struggle. This history of erasure that was experienced by a whole lot of people across the planet. Residing here in America, and being influenced by the American Indian Movement, the Civil Rights Movement, I wanted to learn more about that and there are definitely heroes within those movements.

So, I started with the idea that I was going to do a whole bunch of drawings on maps of the U.S. and a whole bunch of drawings on maps of Palestine. I deliberately chose activists, artists, and scholars because those are people that I’m most influenced by, and honor their efforts by doing two things: one is presenting their image on this map as a way of reclaiming a land that has been denied them. What is a map? A map is a graphic representation of a space that gives us permission to say, ‘Oh, this is America and it reveals roads and states and cities and towns,’ but it also conceals a massive history of destructive dispossession. So, a map is a dual reality, the seen and the unseen. What I wanted to do is reclaim the map, and I started out with Native American activists to reclaim the land by subduing the map by having their faces, their presence, be reemerging from those fields of colors and roads. There’s two things that happen at the same time: one is I want to honor the work of folks that I thought were really important to me, and two is I wanted to use it as an opportunity to really learn a lot about each of them. I made a list and I started to read and read and read, and also listen to anything that was available online, in terms of their presentations and lectures. It was this accumulation of knowledge; by no means am I an expert or scholar or somebody who can talk about these folks with great depth, but it was a way of immersing myself in their work and allowing them to emerge from these graphic fields of domination that represented this history of erasure. They become, in a way (and I say this word with some reluctance, but I can’t think of a better word) the drawings become these micro-monuments for these individuals. They’re not set in stone by any means; they’re kind of scrambles of lines that emerge from a field. From the early stages of this project, the drawings were fairly light and the faces were even more ghostly than they became and I think because I often tend to work and rework drawings, they became a lot more solid in the drawings. This idea of playing with ghosts, of spirits, that have taught me, that have guided me and a lot of others in reflecting on this history of denial, erasure, and oppression.

I wanted to pay homage to them, and I have to admit that there was always this trepidation of, is it my place to make drawings of these human beings, whether they’re Native American, African American because I’m neither? I’m not in any way speaking for them, I’m simply honoring them and it is my place to honor them because they’re remarkable human beings, influential human beings. I wanted these micro, personal monuments spoke to the emergence of African American folks, of Native American folks, of their presence. Not that they’ve been invisible, but they’ve been unseen. What these scholars and artists do is that they make that history seen, they make that history accessible to us, and that’s what this show is about, is helping to make the unseen, seen against these contemporary and historical waves of erasure.

Part of that series was also to address the invisible, or the unseen, work of migrant farmers or laborers. So, there’s a series of drawings of hands. I really just wanted to focus on the hands of laborers, the people that feed us, the people that clothe us, the people that fix our things and build our things. That’s an important part of it because this country is built on bonded hands, of laborers who have been unseen, whether they’re an enslaved population, whether they’re under indentured servitude, or whether they’re very horribly paid and horribly treated laborers. I mean, my refrigerator has apples that were probably picked by somebody who’s getting very little money, so we’re all part of that cycle of consumption that is based on the sweat and blood of folks that we don’t even consider. Not only that, but who are often horrifically mistreated.

Q: Indigenous People’s Day is Monday, honoring the histories and cultures of Indigenous people in America. In thinking about the ideas of displacement and survival you talk about in your work, some of your pieces include the imagery of maps — of the United States and of Palestine — noting their use as political tools that guide “its users to embrace as normal, virtuous, and permanent, a political worldview of a nation that has been shaped by documented histories of genocidal settler-colonial expansion, ruthless and dehumanizing enslavement, as well as exceptionally abusive labor practices that have greatly enriched the settlers.” How has the work you’ve done here caused you to think about your own part in helping to rectify this continued oppression?

A: I’m glad you asked me that question because it’s a really complicated issue to grapple with. As a person of Palestinian descent, as a person who’s really active in thinking about culture and history of displacement, I’m sort of torn because I’m also an immigrant to this so-called nation of immigrants. I challenge the idea that we’re a nation of immigrants; I often will say that we’re really a nation of settlers. So, how do we deal with that history? How do I deal with the history of benefiting from these centuries of genocide, of land theft? I don’t have an answer for that and I don’t know very many people that do, but I address it and I grapple with it. I live in San Diego, right? I live on land that was taken from people and I don’t have a clear answer, so I grapple with that and I’m very uncomfortable. I acknowledge that, as an immigrant, I have to acknowledge my history and my presence as a settler on people’s land. I have to acknowledge that this is their land that I’m occupying, that I’m living on. Hopefully, I’m living on in a thoughtful manner, but I don’t have an answer on how to rectify that history.

Q: Your artist’s statement for “Listening to the Unheard” talks about the ongoing erasure and resistance of Indigenous and formerly enslaved peoples, and our responsibility to these communities. What do you make of the more recent increase we’ve seen to censor and silence books, education, and conversations about the experiences and histories of both the LGBTQ community and people of color? What happens when we don’t listen to, and refuse to see, the people who’ve been historically and repeatedly pushed to the margins?

A: I think it’s an amazingly troubling process, the censorship that’s going on and increasing across this nation. It’s troubling because it perpetuates this history of making these folks unseen and unheard. Whether they’re issues that are addressed currently with LGBT issues, or histories of formerly enslaved populations, or even histories of Indigenous populations that are not told in a comfortable, sensitive, Kumbaya kind of way. These are complex histories and they need to be heard. I think we all have a responsibility to learn, we all have a responsibility to listen, we all have a responsibility to acknowledge that we’re benefiting from this history. When there are questions, I say to folks, “We’re not guilty of our parents’ sins, but we are responsible to learn of the wrongs that they’ve done and how those wrongs benefit us.” That responsibility is an important thing that we take on and I think it’s been denied, it’s been suppressed, it’s been silenced and erased by these efforts to censor books. That is very troubling. It’s an effort by ultra right-wing individuals, or maybe thoughtless individuals, who are afraid to acknowledge that history and are afraid to acknowledge that they’re benefiting from it. I think it’s very troubling. Again, I don’t have answers, but I think it’s a question that we need to address and I think we need to address it in complex ways. It’s not just a black-and-white thing like, ‘Oh, they’re wrong. They’re right.’ I think we need to acknowledge the fear of those who are erasing these histories and say, ‘What’s going on? What’s your fear?’ I’m not saying to justify or coddle it, but I think we need to have complex conversations about these histories and their efforts to censor it are not complex conversations, they’re oppressive acts, but I think we need to be better than that in addressing those acts. But yeah, it’s a very troubling time in America.