Altadena, California

CNN

—

Nearly every day since the Eaton Fire destroyed her home, Dr. Dorothy Ludd-Lloyd’s relatives have tried to get the 88-year-old past the National Guard so she can sift through the rubble.

“We asked at several different stopping points each day if she could just get a piece of gravel,” her granddaughter, Kimberly Cooper, told CNN. “She doesn’t want not just her history, but her parents’ history, to be erased.”

For six generations, the 100-year-old white house on East Mariposa Street – with its teeming flower beds and red shingles – was the family’s center of gravity.

Ludd-Lloyd originally purchased the house in 1972 for her parents; a feat for a Black woman who had been kept from living in the area for decades because of racism, her family said. She later dedicated her life to curating the house in homage to her family’s history.

Now, all that remains are ashes.

For many African Americans who built their lives and businesses in historically Black communities like Altadena, the combined loss of generational wealth and personal heirlooms is indescribable.

CNN spoke to Ludd-Lloyd’s relatives because she still can’t bring herself to talk about everything she lost in the fire. Since learning it could take a few years to fully rebuild the family home, Cooper said her grandmother keeps repeating the same phrase: “I don’t know if I’m going to make it.”

“There’s no words to describe her level of devastation,” she said. “And it’s not about things. She wants people to know that they were there.”

The wildfires raging in Los Angeles have scorched an area larger than the size of Paris and two are already the most destructive in Southern California history.

At least 27 people have died, with 17 of the deaths stemming from the Eaton Fire. Among them was Rodney Nickerson, whose family found the 82-year-old’s remains in his Altadena home.

His son, Eric, told CNN his father was a hardworking Black engineer and veteran who was proud to raise a family in Altadena.

“Everybody was very proud of where they came from up there – and they still are,” he said. “Those that didn’t lose their life, like my dad, some of those people are 80 and almost 90. What do they do? Where do they start?”

The Lake Avenue divide

Nestled at the base of the San Gabriel Mountains, Altadena is about 15 miles from downtown Los Angeles, but for locals it may as well be a world away.

The area has long been racially diverse – African Americans began settling here during the Great Migration, when Black people fled the racism of the South in search of a better life.

At its height, in 1970, Black residents accounted for nearly 30% of the town’s population. Today, that number hovers around 18%. But more than 80% of Black folks who live here own their homes, according to The Associated Press, which is nearly double the national average.

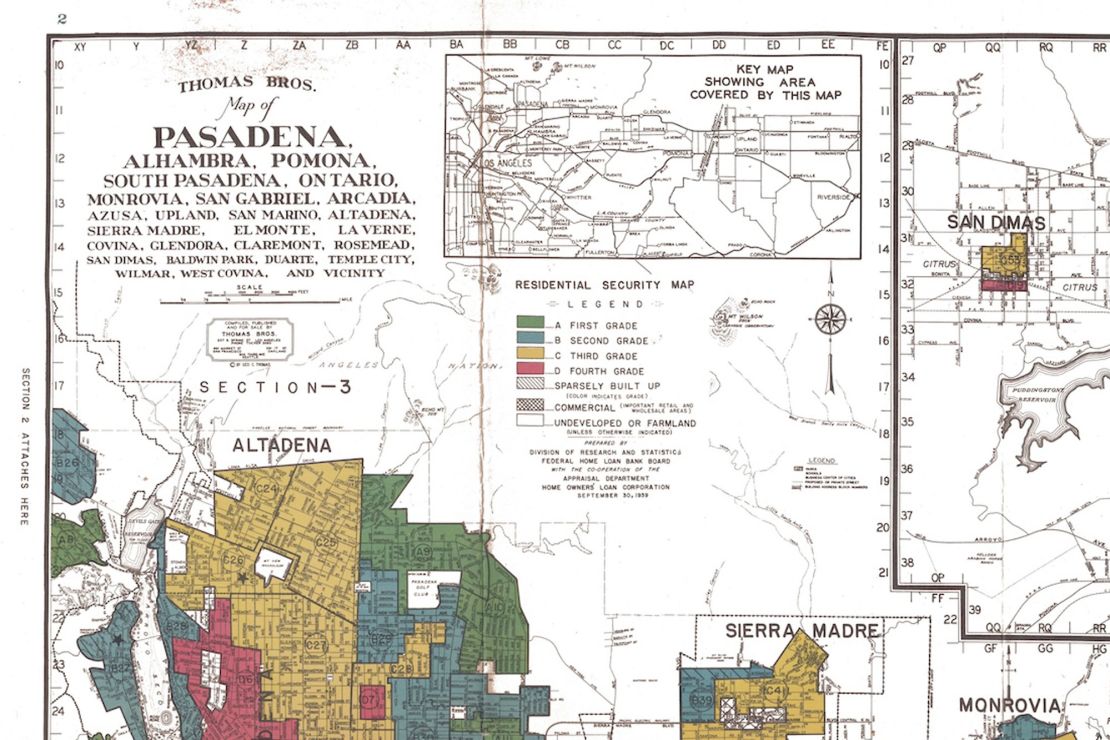

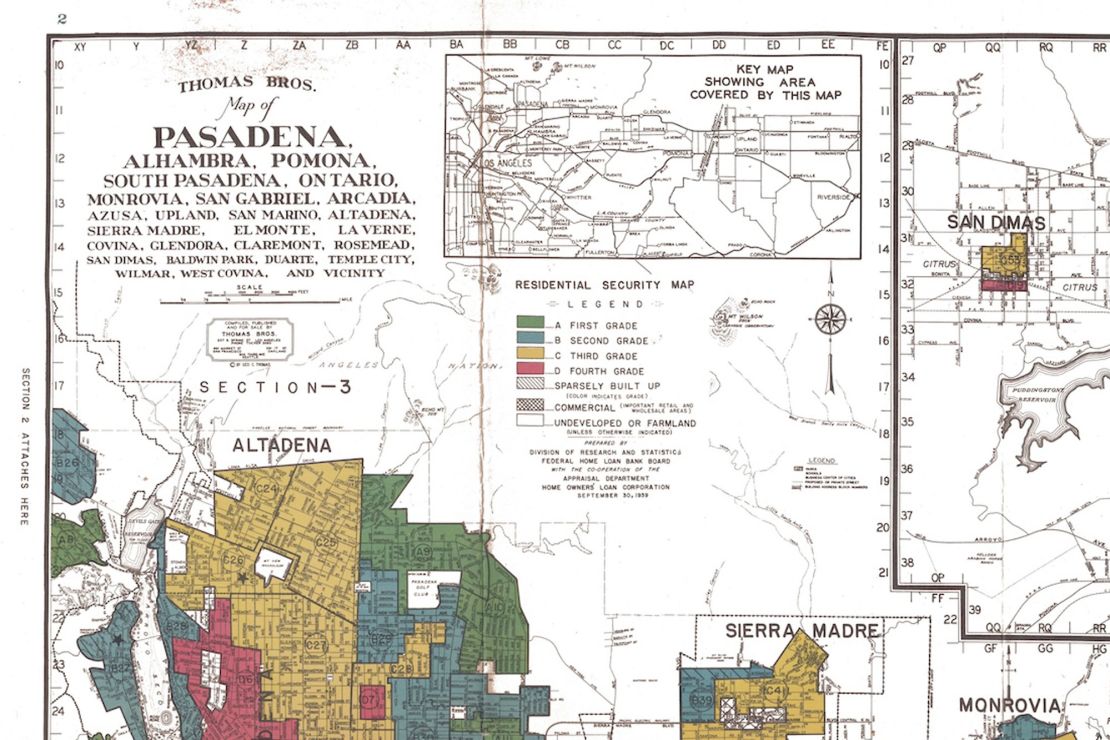

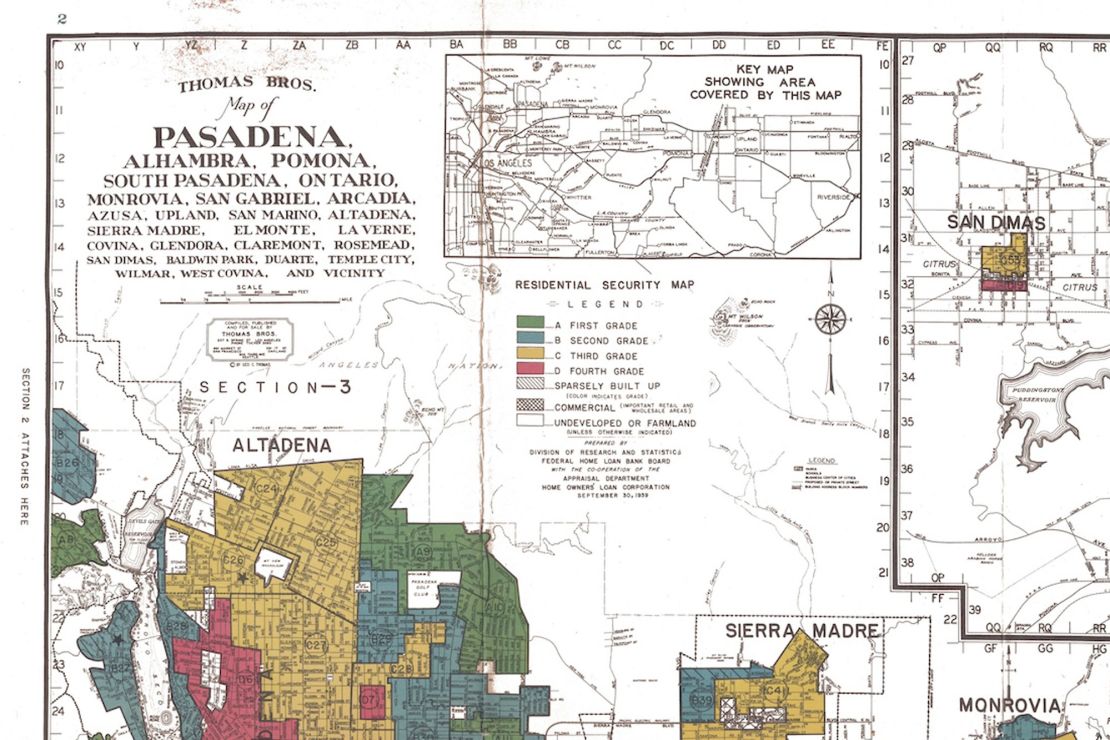

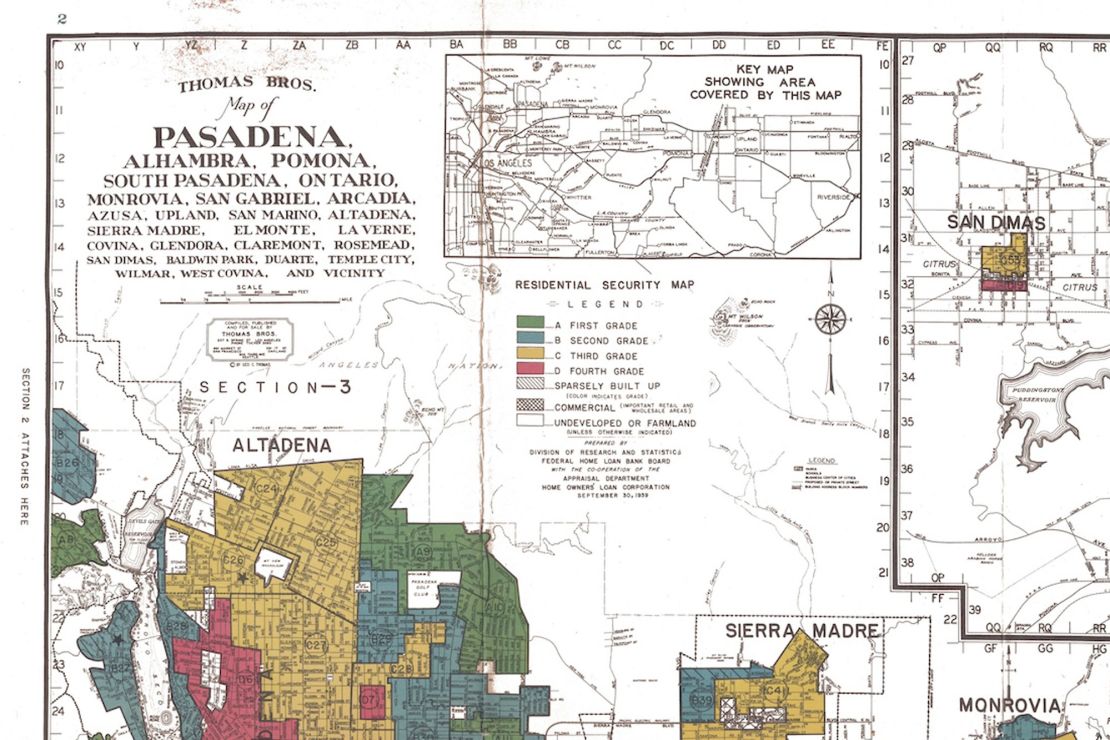

That statistic alone is an accomplishment, given just a few generations ago Black homeownership in Altadena was nearly impossible. In the 1930s, under the New Deal, the federal government mapped out major cities like Los Angeles and began the practice of denying home loans to people of color to promote and maintain segregation.

The maps were color-coded: Wealthy White areas were shaded green, areas covered by racial covenants that prohibited people of color from buying a home were blue, and places “occupied by Negros and other subversive racial elements” were red.

The practice became known as redlining and it thrived for decades until the Fair Housing Act passed in 1968. In the years that followed, racial covenants were deemed illegal, which sparked a White flight to the suburbs that enabled Black Americans across the country to purchase homes for their families in cities.

But vestiges remained. In Altadena, locals saw Lake Avenue as the de facto dividing line between East and West, wealthy and working class, White and Black.

When Ludd-Lloyd bought her home a mere four years after the end of redlining, her nephew said it was a point of pride that she was able to purchase a historic house on the East side of Mariposa Street.

It burnished her list of accomplishments, he said, which already included earning a master’s and her doctorate in education.

“That was a big deal to be a Black family and go from a one-bedroom home in Pasadena with no running water … to Orange Grove and to over to Altadena in the 1970s,” Charles Ludd Jr. said. “That was a huge accomplishment.”

Residents told CNN the culture on the East and West sides of Lake Avenue is different too.

Veronica Jones, president of the Altadena Historical Society, has lived in the area for the last 60 years. She said she and her husband, Douglas, are among the Black families who chose to raise children in west Altadena because it’s the kind of place where “neighbors look out for neighbors.”

“If you have a lemon tree … you make sure your neighbor has some lemonade,” Jones said. “We have the same values, we have the same insights, we eat the same food … the West side has that connection.”

But it doesn’t mean living here is without challenges, even before the fires. Resources are different on the West side, Jones said, and the allocation of the town’s funding has at times felt uneven.

Compared to other locations in east Altadena, Jones said “it was designed to be different. In west Altadena, you have the ‘little park’ and the ‘little library.’” Or at least they did until the fire.

The five-acre green space, named after Charles White, a local Black artist, was also scorched by the flames.

A fire foretold

Author Octavia Butler – best known for penning futuristic tales centered on the Black experience – was born and raised near Altadena.

Her novels were often set in towns that resembled the area and since the LA fires broke out, her book “Parable of the Sower” has been deemed eerily prophetic.

“There’s a big fire in the hills to the east of us,” Butler wrote. “Maybe it was started by accident. Maybe not. But still, people are losing what they may not be able to replace.”

Butler died in 2006; she’s buried at the Mountain View Cemetery and Mausoleum in the heart of Altadena. Although the Eaton Fire tore through the town, much of the cemetery remained unscathed. But others weren’t as lucky.

Black-owned businesses along North Fair Oaks Avenue have been reduced to rubble, including the Little Red Hen Coffee Shop, a local café that’s been a staple in the Black community for the last 50 years.

Barbara Shay, the shop’s owner, said she and her siblings worked extra jobs when she was in high school to help her mother pay the deposit on the restaurant in 1972.

“When my mom worked, people like Redd Foxx and Richard Pryor would come to the restaurant,” she said of the famous comedians. Now, Floyd Norman, the first African American animator hired by Walt Disney, is a frequent customer. But that was before the Eaton Fire destroyed everything, Shay said.

“I’m not functional,” she admits. “I wanted to go and get the pictures off the wall, but I forgot it’s not there anymore.”

Where were the firefighters?

The National Guard has established roadblocks to prevent residents from returning to their homes, as toxic debris and other safety hazards remain. During briefings, the Los Angeles County sheriff’s office also provides near-daily updates on arrests for suspected looting and other crimes.

Jones said when one of her neighbors broke through the line to sneak back into his house, she jokingly told him to be careful.

“He says, ‘I know, I’m carrying a big yellow bag and I’m a Black man.’ And I said, ‘Yes. You’re going to your own home, and you’re asking for trouble,’” she recalled with a wry chuckle at the reality of being Black in America.

The fires have exposed old wounds along the town’s racial fault lines. Maya Richard-Craven says she grew up in ‘Dena, the local nickname for the predominately Black areas of North Pasadena and Altadena. Her brother’s barber shop, her favorite nail salon and so many other places are gone.

In the last week, Richard-Craven said she’s heard from family members and friends who’ve posed the same question: Where were the firefighters?

“It’s really sad that a community with such a rich Black history of prosperity and unity and Black excellence was completely ignored,” she said, adding she feels more resources were sent to the wealthier Pacific Palisades area than Altadena.

LA County officials have defended their response, saying the wildfires exploded in size and in the early hours of battling the blaze, SoCal Edison cut power to the area to protect firefighters from downed lines. But the loss of electricity hampered their ability to pump more water and douse the flames.

“In order for me to fill the tanks, I had to ask the fire departments to stop fighting the fire and that’s a very tough operational decision to make,” Janisse Quiñones, chief executive engineer of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, said during a news conference last week.

But for some, that explanation does not go far enough. And as investigations into the origins of the fire continue, civil rights attorney Ben Crump has filed a wrongful death lawsuit against Southern California Edison, alleging their mismanagement led to the Eaton Fire.

California Rep. Sydney Kamlager-Dove told CNN she wants a “full-scale investigation” into the wildfire and the emergency response.

“I and the CBC, the Congressional Black Caucus, for example, are curious about who decided to sacrifice Altadena, a historically Black community in the LA County area,” she said.

Although it’s too soon to begin thinking of rebuilding, Veronica Jones said she hopes when the time comes, Altadena does so with an eye toward equity.

“It’s an opportunity to still erase some of that redlining,” she said. “That could really be a change if things really started to move toward being more equal.”

Back to Mariposa

In the wake of such incomprehensible loss, Dr. Dorothy Ludd-Lloyd has taken to carrying around a photo of her house before the fires, and she happily describes it to anyone who will listen.

The walls were decorated with oil portraits she hand-painted of their ancestors and the mail rested on her mother’s original Singer sewing machine. Drawers held letters her father sent home during World War II and the family dined on a table and linens that had been with them for nearly a century.

Generations of cousins took the same picture on the living room steps and after Christmas dinner, the family settled around the fireplace with a slice of coconut cake to talk about how they could help the Altadena community.

Now, that fireplace is one of the few things that remains.

Across the centuries, storytelling has played a pivotal role in preserving African American history and culture. After the Eaton Fire, Cooper said her family will have to rely on their collective memories to preserve their legacy.

“We may not have the physical things, but we have the oral traditions,” she said. “And we’ll be keeping those traditions alive until we can get back to Mariposa.”

CNN’s Michael Besozzi contributed to this report.