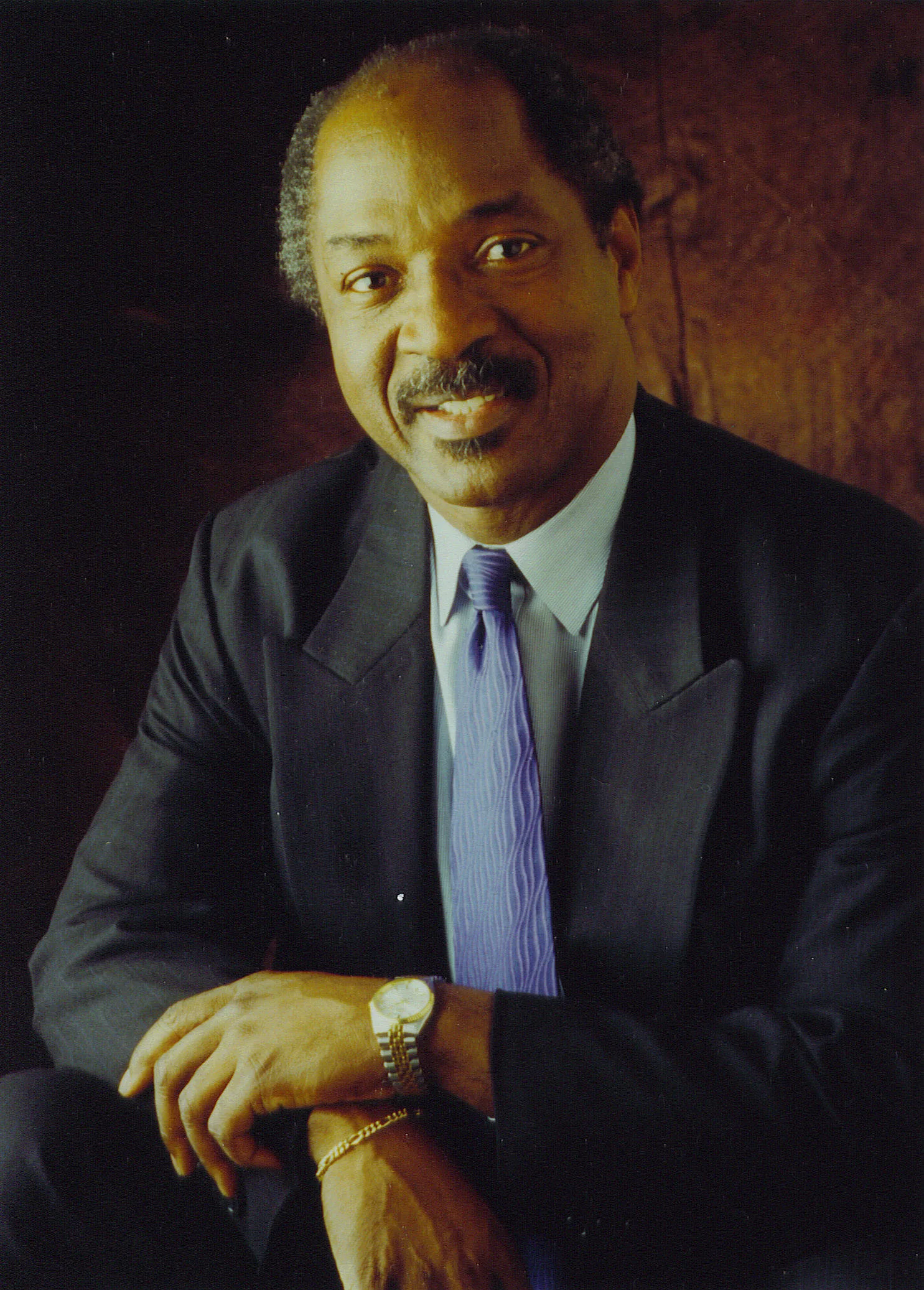

Charles James Ogletree Jr. was born in 1952 in Merced, California, in the state’s Central Valley, a region whose harsh labor conditions and reliance on low-wage migrant labor were memorably depicted by John Steinbeck in The Grapes of Wrath — a portrait, Ogletree later recalled, that “remained very much a reality” when he was growing up. The child of seasonal farmworkers, Ogletree’s family struggled to make ends meet, moving from one cramped apartment to another throughout Ogletree’s youth.

Despite financial hardships — and despite the racial divisions that afflicted Merced —Ogletree and his family took comfort in their community. “In south Merced, as in many other African American communities contending with segregation at the time, one found ways to create one’s own centers of excellence, in a community short on resources,” he wrote in All Deliberate Speed, his personal history of growing up as a beneficiary of Brown v. Board. He fondly recalled the local institutions where the Black citizens of Merced gathered, shopped, and worshipped. Today, a courthouse in Merced bears Ogletree’s name, following the passage of a bill that was introduced by former California assemblymember Adam C. Gray — in collaboration with the NAACP — and passed by California Governor Gavin Newsom in 2022.

But the most important institutions in Ogletree’s upbringing were public schools. Although neither of his parents had finished high school, they urged him to take his education seriously. His grandmother’s frequent recitations from the Bible awakened a love of reading in Ogletree, a love fueled by his elementary school’s librarian, who kept him regularly stocked with new books. “Books were my addiction, and I could not feed it fast enough,” Ogletree wrote. “… It was becoming apparent to others around me, but not to me, that reading would be my ticket out of poverty and despair.”

Reading also deepened Ogletree’s understanding of racial injustice in the United States. “These books awakened a consciousness that I didn’t realize was within me,” he wrote in his memoir. “…I used this knowledge to take on new challenges in school. My generation, having been sheltered from much of the discrimination that our parents had experienced, took a different approach on issues of race. We did not fear white people. We did not feel unequal. We had no reluctance to speak and be heard.”

Ogletree certainly made his voice heard at Stanford University, where he matriculated as a freshman in the fall of 1971. He soon became involved in campus activism and politics, organizing a student group in support of political prisoners and chairing the Black Students Union. When the University announced that the speaker at Ogletree’s commencement ceremony would be Daniel Patrick Moynihan — who a decade earlier had published a controversial report that reinforced many racist stereotypes about African Americans — Ogletree and his peers faced a difficult decision: “Do we attend graduation since it means so much to our families and us? Or do we boycott out of respect for our families and as a tribute to them?” The group decided to hold a separate graduation ceremony for Black students — now a Stanford tradition — and to attend the entirety of the regular commencement except for Moynihan’s speech.

Ogletree went on to Harvard Law School, arriving in Boston just as the city was engulfed in bitter conflict over orders to desegregate the public schools. Ogletree soon became involved. “Just across the river, a race war was in progress, and I could not sit in the relatively obscure quiet of my law school classroom and ignore it,” he recalled. He and some of his fellow law students began volunteering at the local NAACP chapter, helping families file claims of racial harassment against their children.

Busing wasn’t the only legal controversy Ogletree was involved in during law school. As national chairman of the Black Law Students Association, he advised Harvard Law Professor and former Solicitor General Archibald Cox on the issues at stake in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, which was argued before the Supreme Court in fall of 1977. Cox had been hired by the University of California, Davis to defend its use of racial quotas in its admissions program. Ogletree also traveled to Washington to meet with incumbent Solicitor General Wade McCree, and he was present for the arguments. Although the Supreme Court upheld affirmative action in general, it struck down the use of racial quotas, a decision Ogletree lamented. “Put simply, Bakke marked the end of the radical challenges to the status quo. … With one decision, the Court accelerated the process of undoing Brown.”

“I mourn the passing of my dear friend, my brother in struggle and my stalwart colleague, Charles Ogletree. I have known “Tree” since our law school days, when he was the president of the National Black American Law Students Association (now BLSA) and I served on its Board,” said Former LDF President and Director-Counsel Ted Shaw. “During that time, Tree led us in opposition to the Bakke case, which was in the Supreme Court. It was apparent then that he was a born leader with a powerful intellect. Tree lived an extraordinary life — D.C. public defender, public intellectual, Harvard Law School professor, teacher of and mentor for generations of lawyers-in-training including Barak and Michelle Obama, attorney for Anita Hill during the Clarence Thomas nomination hearings, attorney for survivors of the Tulsa massacre, advocate for black reparations, LDF Board member, and so much more. We walked a long way through life together. Now he walks with the ancestors. I am diminished by his passing, but I am comforted that peace has come to him. My thoughts are with Pam, and with Rashida, Charles III and the grandchildren and family. I know that they will be sustained by their memories of Tree as a husband. Father, grandfather, and one of our great ones.