Looking out through the thick summer air at the fields of the Whitney Plantation Museum, tucked away on the banks of the Mississippi River outside of New Orleans, we could imagine more than 100 enslaved people picking indigo or cotton under the unrelenting sun. Etched on the black stone in front of us were personal accounts of these men, women, and children, who were forced to labor to their deaths.

Along the dirt path that lines the fields are cabins that housed enslaved people. They were not dissimilar from the three wooden shanties that lined the driveway of our family home in Fort Mill, S.C., where our grandparents’ cook, chauffeur, and chauffeur’s son lived.

The grounds of “The White Homestead,” owned by our family for generations, is where we grew up. Our grandparents lived in a classic Southern “big house,” and we lived in another home on the property.

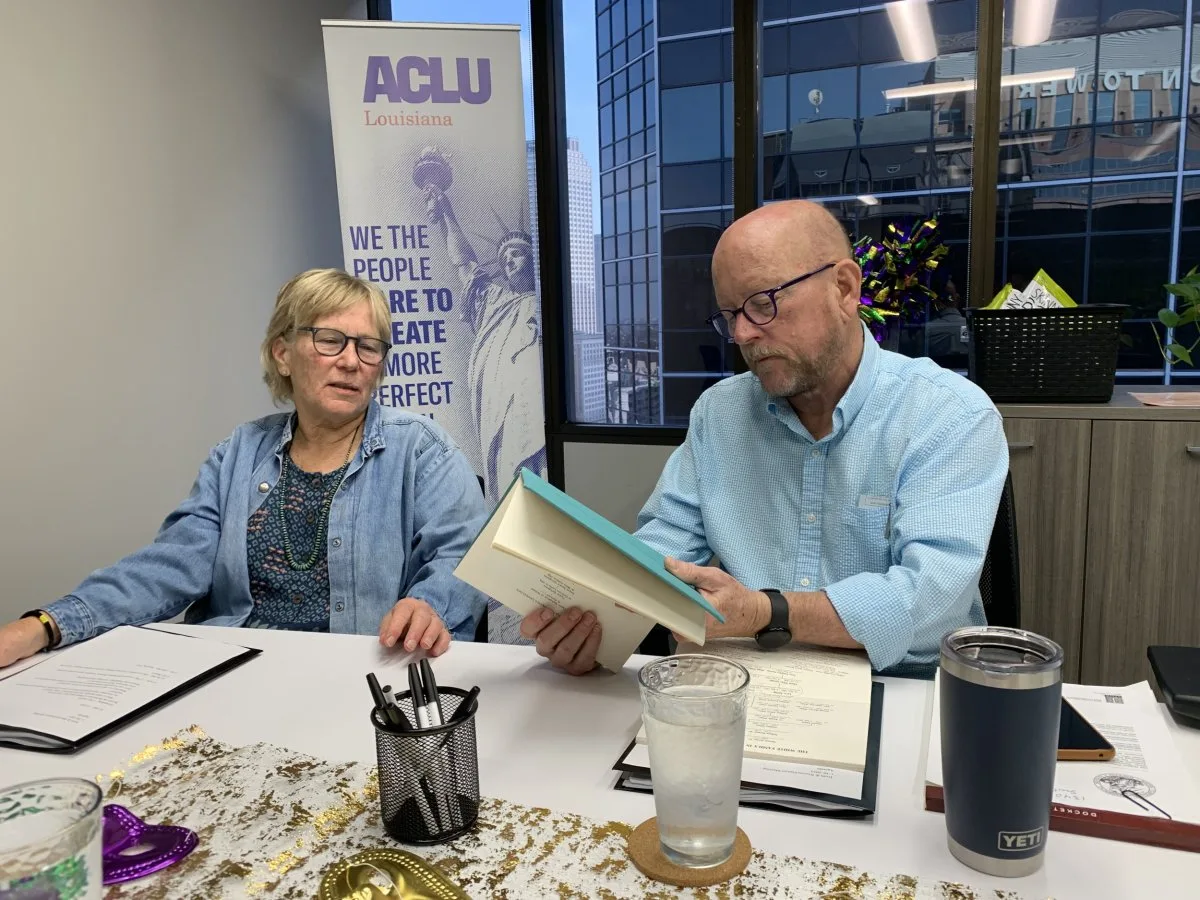

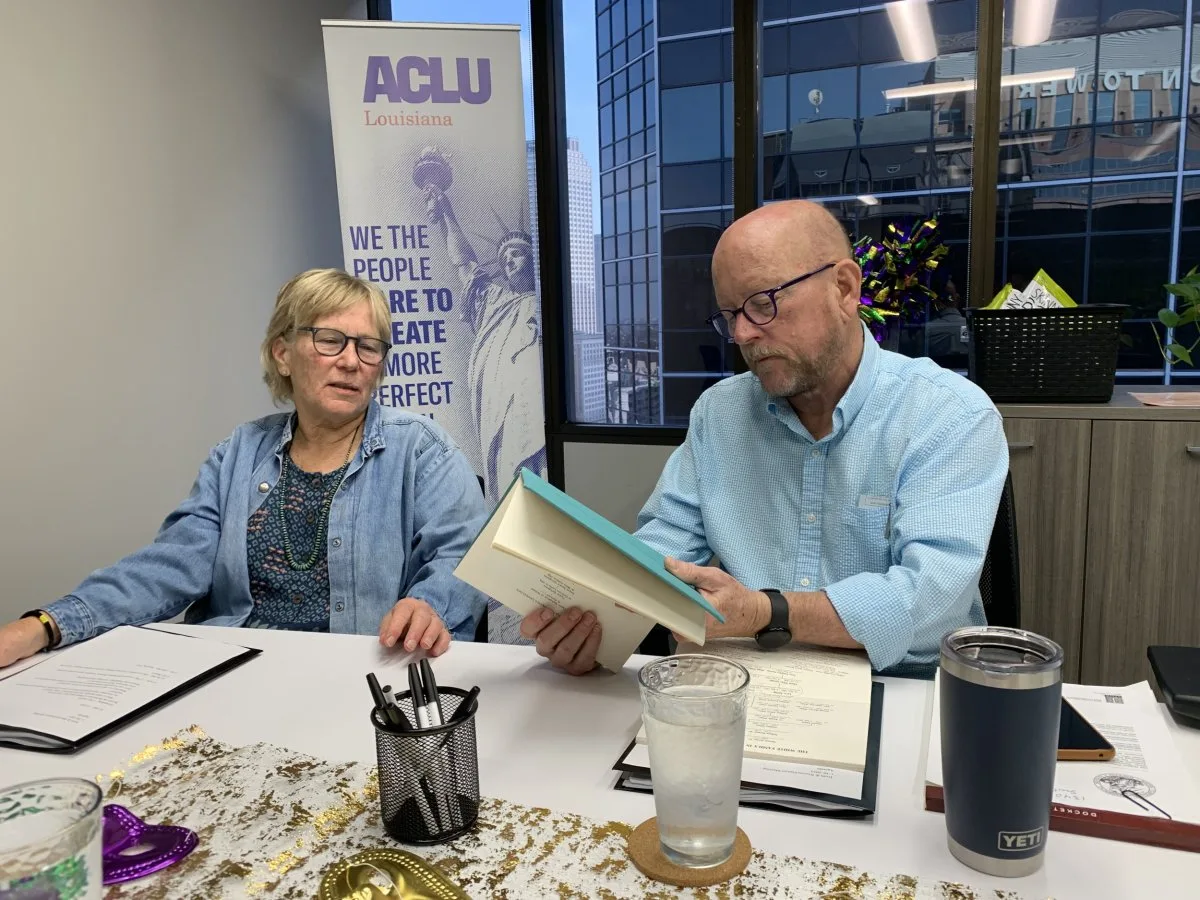

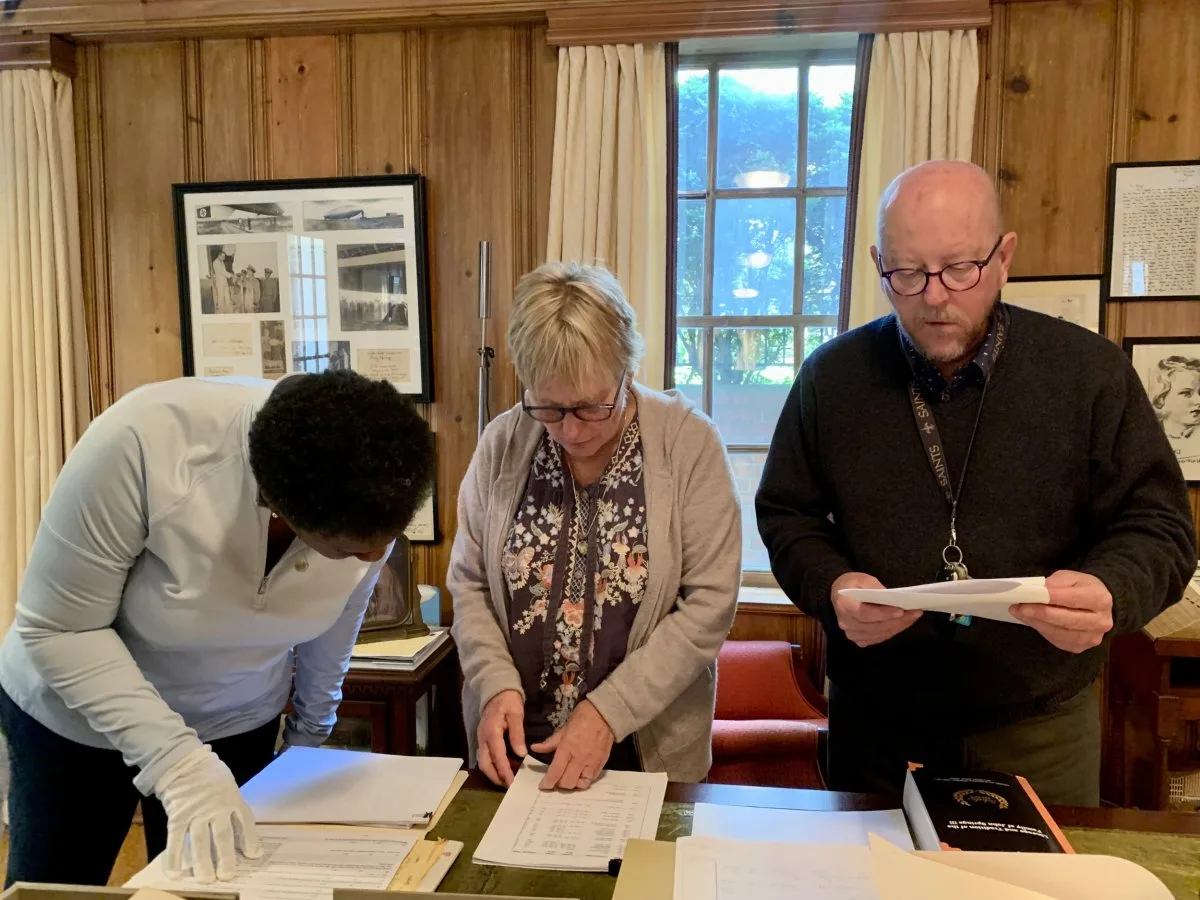

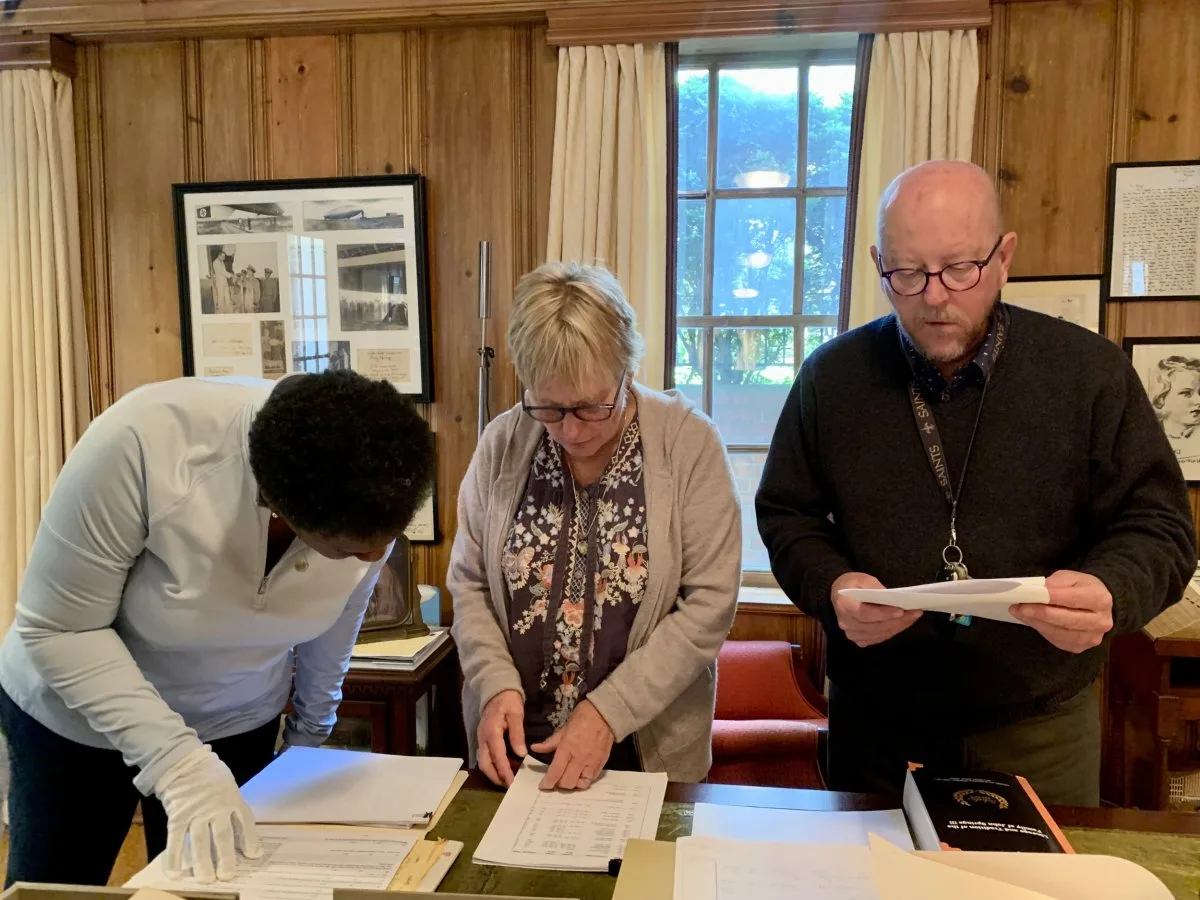

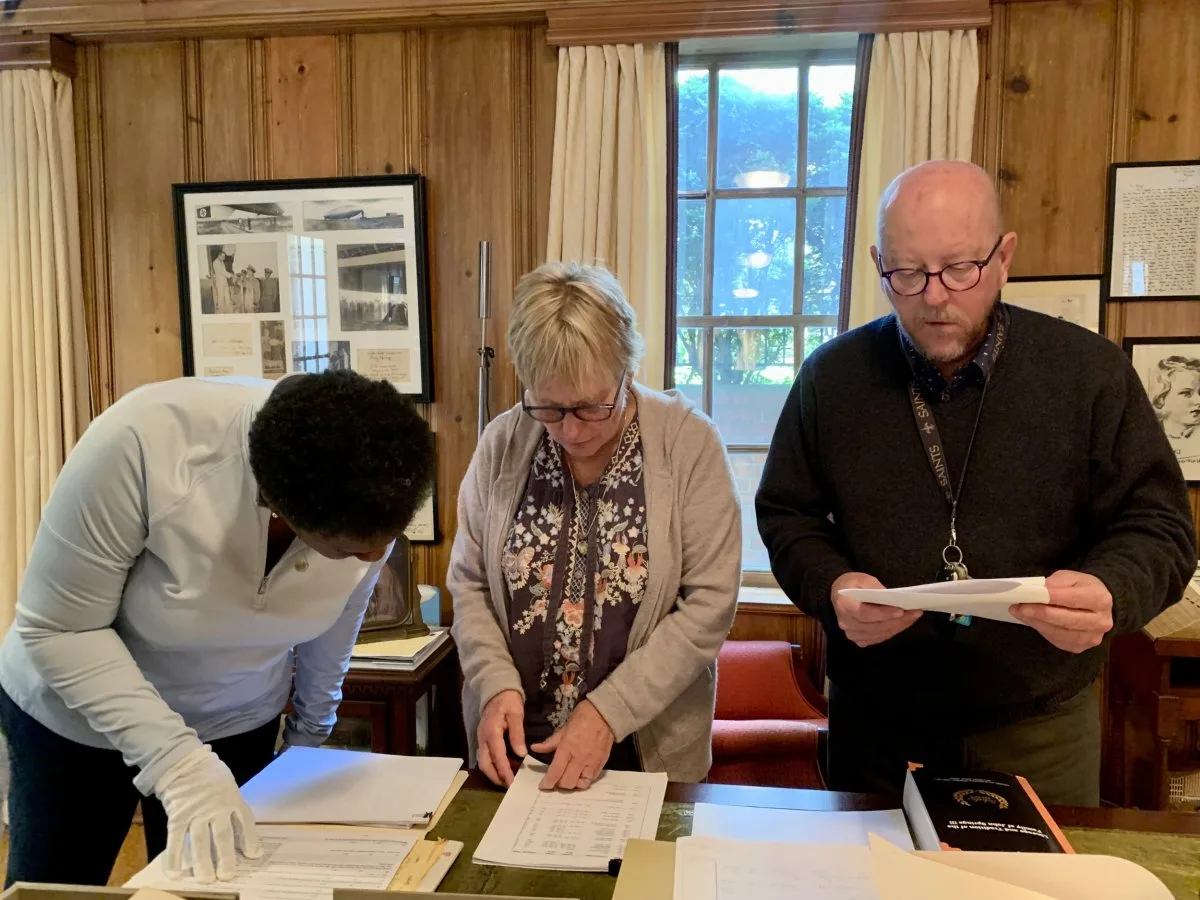

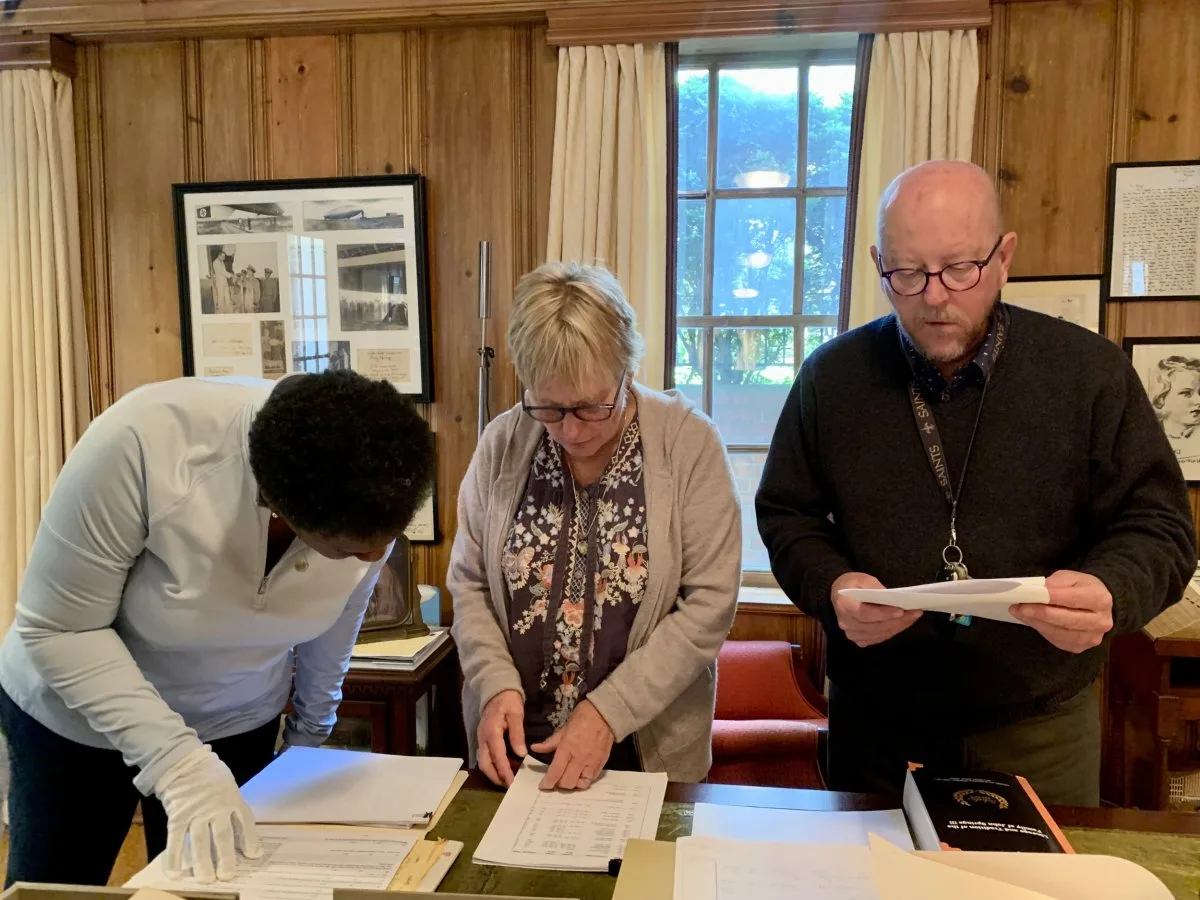

Photo Courtesy of ACLU

Our grandparent’s house held amazing artifacts: a cradle where, we were told, Napoleon had slept; the wing of a German plane our grandfather shot down in World War I; an original signed copy of South Carolina’s secession declaration; and documents pardoning our ancestors for taking part in the late rebellion, also known as the Civil War. The shelves were lined with books telling the story of the gauzy Old South.

What those books did not tell us was the truth about slavery, its brutality, and our family’s part in it. To us, our family history stopped and started with our grandfather. He was a World War I hero, an author, and had taken the mill owned by his father and turned it into a textile empire.

It was never discussed that the textile business was started with profits from enslaved labor, nor that our ancestor had a prominent role in the slave trade. For 30 years, our great, great, great grandfather John Springs III would travel annually to Maryland or Virginia to purchase 40 human beings at a time, separating them from their families, and marching them South in chains and ropes.

In the words of historian Michael Tadman, “in buying his slaves, Springs would have broken slave families routinely, but his South Carolina clients would have seen him as a savior, bringing the labor that they felt was essential for their economic success.”

Discovering this fact about Springs, during the summer of 2022, is what first brought us to the Whitney Plantation Museum—to find out more about what our grandparent’s home once was, generations ago.

Reckoning and Repair

For us, the benefits of slavery have not ended. They are a very real part of our day-to-day lives. The institution of slavery allows us to have high incomes without having to work. It allows us the luxury of feeling secure in our lives. In contrast, the descendants of the people owned by our ancestors have had the opposite experience. Many experience poverty, and all experience structural racism, especially those in the South.

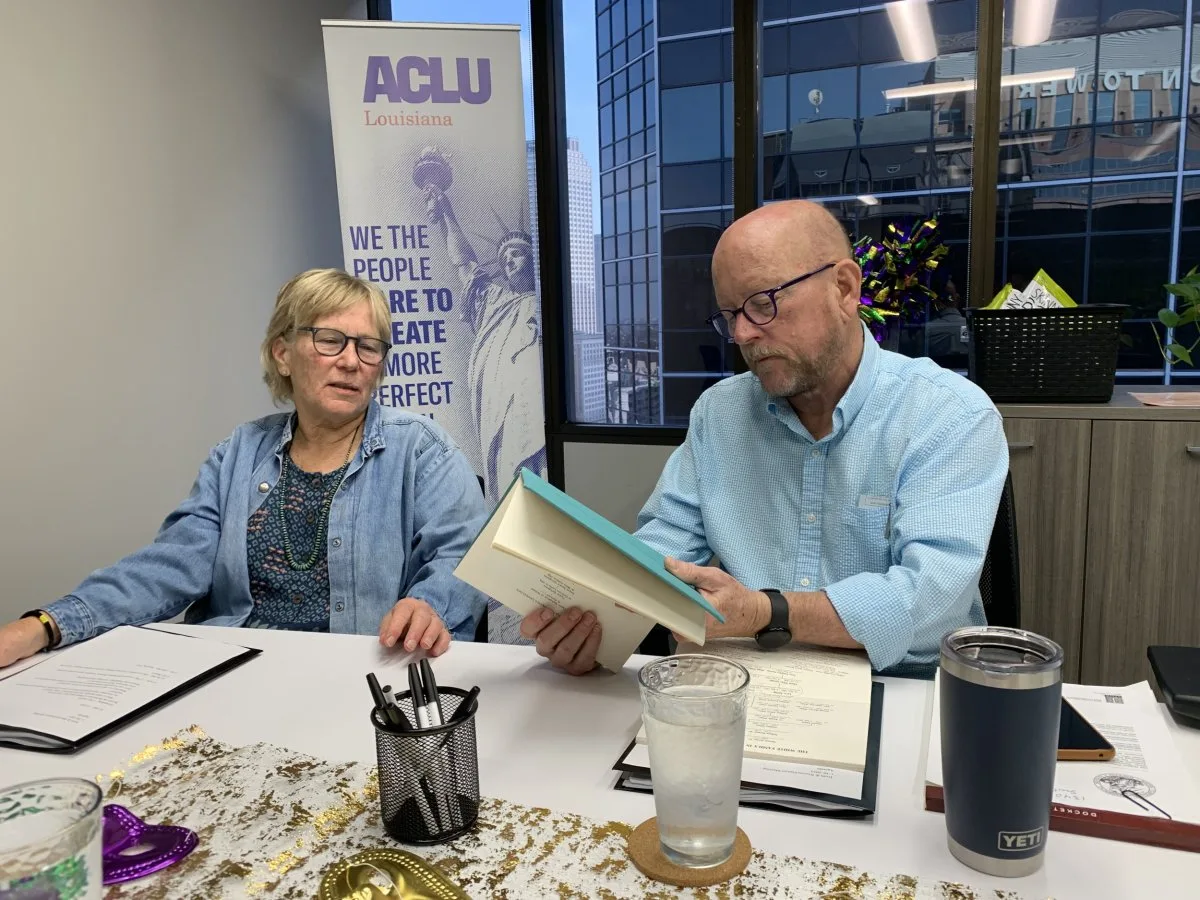

Photo Courtesy of ACLU

Once we learned how our family’s participation in the enslaving of people directly and literally enriches our present, we asked ourselves, what do we do as a result of this knowledge?

Our family has a long history of philanthropy and investment in Fort Mill. We have done, and are doing, a great deal of good for the community. However, we recognized the harm not only of our past history, but the on-going harm of our wealth that has been taken from others.

We’ve studied, with guidance from the ACLU of Louisiana, the arc of slavery to mass incarceration and racist policing, overlayed our family history onto that arc, and designed a pilot program that will allow us to begin to create our version of reparations. We have benefited from the legacy of slavery, so we decided to help those who have been hurt by that same legacy.

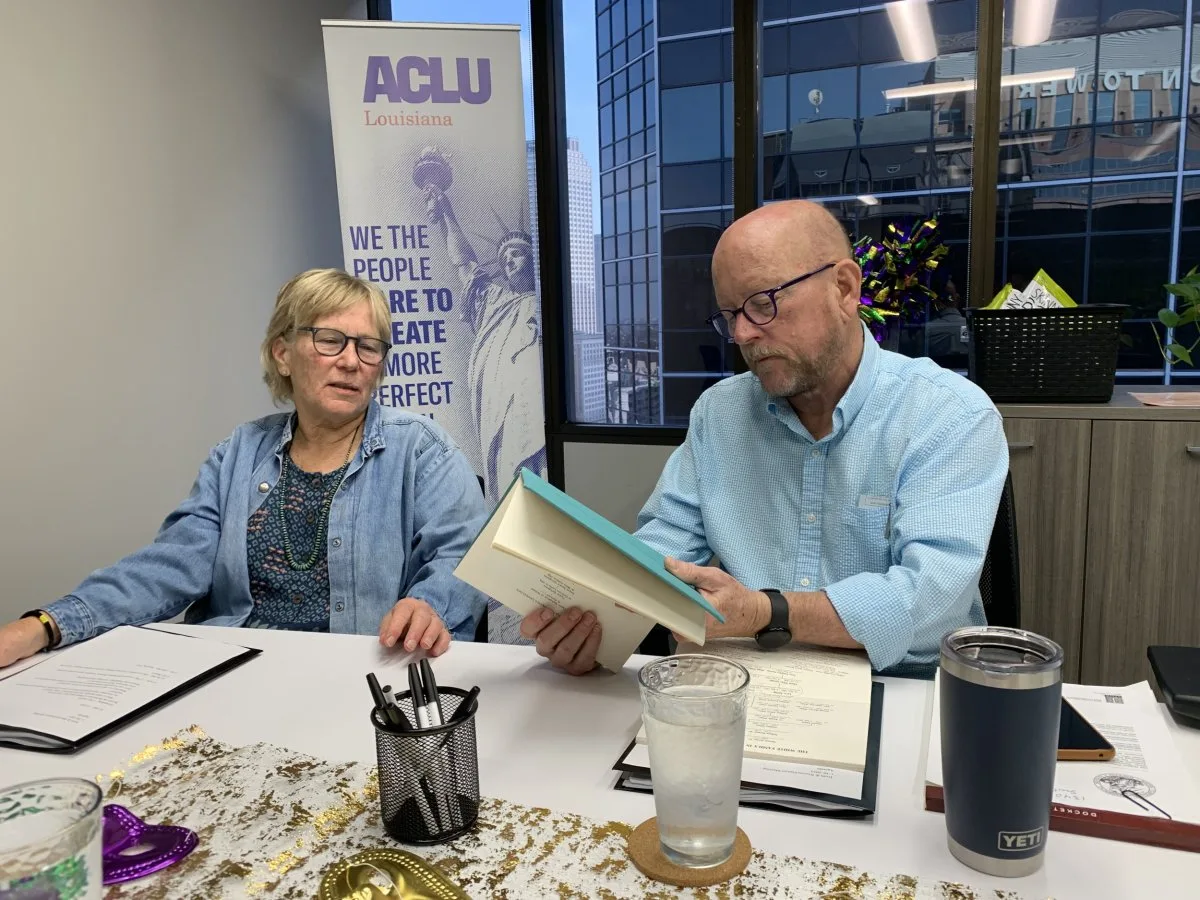

Photo Courtesy of ACLU

Through the ACLU of Louisiana’s Justice Lab, we have set up a guaranteed income program for survivors of racist and violent policing. We hope that the funds provided, in addition to optional holistic programming, such as free counseling, financial literacy, and career services, will empower these individuals to have some of the sense of security that we have.

The decision to take this first step was not a hard one. People in similar positions as ourselves may be afraid to ask questions about their own history because they are afraid of the answers. But we have asked those questions and did not find anything to fear. Today, we encourage those of you whose families share our history as enslavers to consider doing the same. We have found joy in sharing our wealth and expect you will too.

Buck and Gracie Close are siblings raised in Fort Mill, S.C.

The views expressed in this article are the writer’s own.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.