MANTUA, Italy — The Italian government has agreed to pay Holocaust reparations on behalf of Germany in July via a newly established fund, drawing a mixed reaction from the country’s Jews.

The fund was approved by the government of former prime minister Mario Draghi in April 2022, after a legal battle in the UN’s top court between Germany and Italy over continued civil claims against Germany for Nazi war crimes.

Last month, the fund was officially allocated 61 million euros (roughly $67 million), which will be made available incrementally over the coming years through 2026. The money is earmarked to compensate victims of Nazi crimes including Jews, Roma, and political prisoners.

Bice Parodi, the daughter of an Auschwitz survivor who lost her entire family in the Holocaust, was quick to file a claim with the fund.

“My sister and I sued as a matter of principle,” Parodi told The Times of Israel. “The Italians have never really come to terms with the past. In Germany, there was the Nuremberg trial, but in Italy, after the liberation, there was no in-depth reflection on what had happened during fascism.”

Parodi said that her now-deceased mother, Piera Sonnino, was a writer who worked to educate about the Holocaust. Sonnino received a stipend as a result of the 1961 Bonn Accords which saw Germany pay Italy the equivalent of 1.5 billion euros ($1.65 billion) in today’s money, said Parodi. But, she said, she and her sister are making the additional claim to “spread greater awareness among Italians.”

According to Filippo Biolé, the lawyer who filed the new claim on behalf of Parodi, the Bonn Accords fell short of sufficiently helping the victims.

“These agreements provided for Italy to indemnify Germany from further claims for compensation, but this settlement didn’t cover the requests that could have been presented by private Italian citizens in the following years,” said Biolé.

Meanwhile, the Union of Italian Jewish Communities (UCEI) harshly criticized the new fund for similarly seeking to shuck responsibility for private claims.

“Although the fund has been established, lawyers for the Italian government have argued that the 800 claims that have been filed are barred by the passage of time — even though they are crimes against humanity and, as such, should not be past the statute of limitations,” said UCEI vice president Giulio Disegni.

Disegni called the stance “a contradictory position that has left the Jewish world speechless.”

The Italian Government Press Office did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

In its first iteration, the bill establishing the fund in 2022 gave a deadline of 30 days from the date of publication for victims to file a claim.

“It would have been very difficult to decide to sue, collect the documentation and choose a competent lawyer in such a short time,” said Disegni. “The deadline has been extended several times, [most recently] until June 28, 2023.”

The bill’s approval last year aimed to help resolve a longstanding legal and diplomatic dispute between Italy and Germany, after a Rome court allowed several German properties to be foreclosed on to compensate victims suing Germany for Nazi crimes. The fund allows Italy to pay out to claimants instead of Germany, theoretically placating Holocaust victims and their families together with the German government.

But according to Biolé, the 61 million euros allocated in July by the government of Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni are insufficient in light of the more than 800 pending lawsuits involving over 13,000 people (many lawsuits are collective or class action).

In 1938, Italy under fascist dictator Benito Mussolini enacted anti-Jewish laws severely restricting Jews professionally, commercially, and socially. A total of 7,680 of Italy’s 44,500 Jews died in the Holocaust after Germany occupied parts of Italy in 1943.

Biolé said there has already been talk of increasing the sum, particularly in light of a recent Constitutional Court ruling that compensation must be paid in full by the Italian state.

According to Biolé, the government is trying to pay as little as possible and has established the fund through a provisional decree — an emergency measure that doesn’t require a vote — thus circumventing parliamentary debate on the topic and avoiding media attention.

Biolé said that the low sum reflects the extremely short 30-day window the government initially allocated for filing claims and that the extensions were only granted after the original time frame aroused indignation from those involved. He added that government lawyers have furthermore requested that prior payouts compensating for Nazi war crimes be deducted from the sums awarded to victims by the courts.

A deeply personal matter

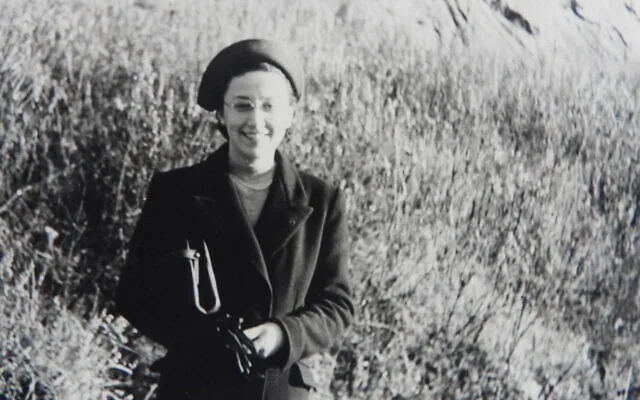

Parodi’s mother, Piera Sonnino, lost her entire family in the Nazi death camps. In 1944, at the age of 22, she was arrested along with her parents, Ettore Sonnino and Giorgina Milani, and five siblings, Paolo, Roberto, Maria Luisa, Bice and Giorgio, due to an informer who betrayed them in exchange for a reward. They were all deported to Auschwitz.

“My grandparents were immediately sent to the gas chambers because they were considered too old,” said Parodi, “and my uncles died before their sisters because they were more fragile.”

“Maria Luisa was transferred to Flossenbürg, where she was killed, while Bice died of hardships and diseases, buried under the snow outside a shack, under the eyes of my mother who every morning passed by her sister’s corpse.”

When she returned to Italy from Auschwitz, Sonnino discovered the identity of the whistleblower.

“Once home, my mother underwent five years of treatment in the hospital to get back on her feet,” Parodi said. “In that period she researched to find out what had happened to her relatives and learned who had betrayed them. The price of a Jew was 1,000 lire. The informer earned a total of 8,000 lire, which was more or less equivalent to eight months’ salary at the time.”

Parodi said that when her mother returned home to Genoa she tried to drive social and political change with her personal story, working hard to educate people about the scope of the tragedy for Jews, Roma, homosexuals, and communists.

In the 1960s, Sonnino wrote a diary titled “La notte di Auschwitz” (“The Night of Auschwitz”). In 2004 the memoir was published with the title “Questo è stato. Una famiglia italiana nei lager.” The English edition, published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2006, is titled “This Has Happened: An Italian Family in Auschwitz.”

Biolé doesn’t just represent Parodi; he has also sued Germany on behalf of his own family to obtain compensation for the murder of four relatives — his great-uncle Bruno De Benedetti, his aunt Ida Foa, her husband Arturo Valabrega and their son Luciano Valabrega — who died in the concentration camps of Dachau, Auschwitz and Flossenbürg,

Biolé and his relatives were among the first to file a claim in May 2022, shortly after the fund’s establishment was announced. According to Biolé, many people waited to make claims due to the drawn-out legal dispute between Germany and Italy, which now seems to have ended with the creation of the fund.

“For the family members, it’s very painful to relive such dramatic events,” Biolé said. “That’s why in the past, many people did not even try to ask for compensation until the opportunity offered by this directive presented itself.”

According to the Union of Italian Jewish Communities’ Disegni, however, the funds allocated by the Meloni government are not nearly commensurate with the heinousness of the crimes committed.

“In general we think that this directive is a joke,” Disegni said.