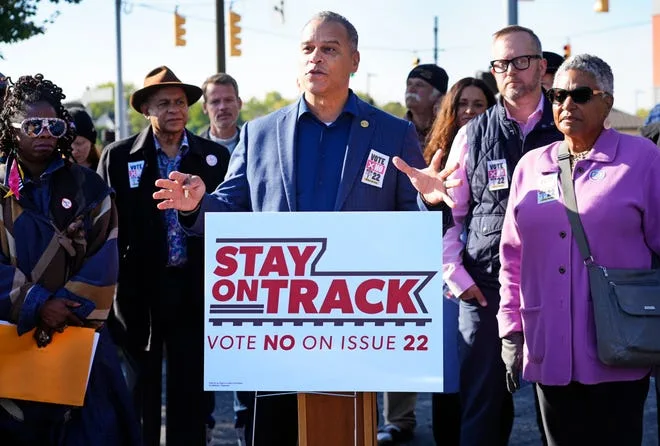

As soon as Joe Mallory stepped to the microphone to start the press conference on Oct. 11, he knew the political debate over Issue 22 was getting weird.

Mallory, the leader of Cincinnati’s NAACP and brother of a former Democratic mayor, stood a few feet in front of Tom Brinkman, a former Republican state representative and one of Cincinnati’s most conservative politicians.

Neither man could recall the last time they’d agreed on much of anything, but there they were, standing together under an oversized “Vote No” banner. When Mallory said Issue 22 was bad for Black neighborhoods, Brinkman applauded. And when Brinkman called Issue 22 a “crooked deal,” Mallory nodded his approval.

Weeks later, Mallory still marvels at the strangeness of the moment.

“That hasn’t happened before,” he said.

And yet, it keeps happening. Unlikely alliances and unexpected rivalries are springing up all over Cincinnati in response to a ballot issue that has defied the tribal rules that govern so much of American politics today.

Issue 22, which asks the city’s voters for permission to sell the Cincinnati Southern Railway, exists in a kind of alternate political reality, one in which traditional battle lines between Democrats and Republicans are barely visible.

Instead, the campaign divides those who trust the powerful people behind the $1.6 billion deal and those who don’t.

It’s created a topsy-turvy, dogs-and-cats-living-peacefully-together vibe that has united odd couples like Joe Mallory and Tom Brinkman while dividing traditional allies, such as Mallory and his brother, former Mayor Mark Mallory, who backs the sale.

Strange bedfellows have emerged on both sides of the Issue 22 campaign: Conservatives and progressives, business leaders and union members, environmentalists and railroad company executives. The issue also is backed by five former mayors, including Roxanne Qualls and John Cranley, who ran against one another.

They all may have different reasons to support or oppose the sale, but those reasons are enough, at least for now, to sustain partnerships that didn’t exist before Issue 22 and might never happen again.

“It doesn’t line up along any political spectrum we’ve seen before,” said David Niven, a University of Cincinnati professor who studies political campaigns. “This would be like Bernie Sanders and Ted Cruz finding common purpose on something.”

A strange issue leads to strange politics

One reason the politics around Issue 22 are so unusual is that Issue 22 is among the most unusual ballot issues Cincinnati voters have ever seen.

If approved, the measure would allow the independent board that oversees the 143-year-old railroad to sell it to Norfolk Southern Corp. for $1.6 billion. That money would be deposited into a trust overseen by the railroad board, which would disburse no less than $26.5 million a year to the city to fix or replace city streets, bridges, buildings and other public spaces.

Supporters say it’s a great deal and believe the annual disbursements could be substantially higher than the $25 million Norfolk Southern currently pays to lease the railroad, which runs 337 miles from Cincinnati to Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Opponents say the proposed sale is a huge risk. They worry about how money from the sale will be spent and they argue the railroad – the only city-owned railroad in the country – is a public asset that should stay in city hands.

The difference between those who support or oppose the plan often comes down to whether they believe city officials and other Cincinnati power brokers can be trusted to make this deal and to spend all the cash that comes with it.

Opponents are suspicious about a great many things. Will proponents of the sale do what they say they’re going to do? Will they steer money to pet projects? And if everything is on the up and up, why didn’t they allow more public discussion before putting Issue 22 on the ballot?

Joe Mallory and Brinkman both touched on why they’re skeptical at the press conference on Oct. 11. For Mallory, it was about poor neighborhoods and people of color being left out of the decision-making process.

For Brinkman, it was about a profound distrust of the government’s ability to spend the money wisely.

“We’re tired of being left behind and forgotten,” Mallory said.

“It’s just a bunch of baloney,” Brinkman said.

Abby Friend, a leader of the anti-Issue 22 campaign, said that kind of skepticism unites many in the opposition, despite their other political differences. The campaign against Issue 22 includes liberals, conservatives, socialists, libertarians and charterites.

“It’s not a generalization to say a big thing that’s connecting us all in this is a distrust of politicians,” said Friend, who describes her politics as left-of-center. “There’s more to it than just distrust, but distrust definitely does lie at the core of it.”

She said that distrust is well-earned. Three Cincinnati City Council members have faced corruption charges in the past few years and polls have found Americans’ trust in government overall is near an all-time low.

Those are the political headwinds confronting Issue 22. “This isn’t a good financial deal,” Friend said. “It’s a good political deal for the politicians in power.”

Odd alliances and brother vs. brother

But the motivations of supporters and opponents can be complicated. The Ohio Environmental Council, a Columbus-based nonprofit, announced earlier this month that its political action committee would support Issue 22 because the railroad sale would bring in more money to invest in “environmentally-friendly infrastructure.”

“This sale is a crucial step toward creating a healthier community,” the council’s director, Spencer Dirrig, said in a statement.

The council’s website says it is dedicated to preventing pollution and creating more sources of clean energy. And its endorsement argues the railroad sale will advance that mission for decades to come.

But the endorsement also put the council on the same side of Issue 22 as Norfolk Southern, the railroad company that’s still cleaning up toxic waste left behind after one of its trains derailed in East Palestine, Ohio, in February.

The derailment is one of the worst environmental disasters in Ohio in years.

For every odd alliance there’s also an unusual divide. The NAACP and the African American Chamber of Commerce both work to support Black businesses and predominantly Black neighborhoods, but the chamber supports Issue 22 and the NAACP does not.

Perspective is a big reason why, according to Joe and Mark Mallory. Their differences on Issue 22, they say, are based on their different approaches to achieving the same goal: improving the lives of city residents.

A similar split arose a few years ago when Mark favored building FC Cincinnati’s stadium in the West End and Joe opposed it. Now, in a new dispute that’s also about development and money, they’re on opposite sides of Issue 22.

“Go find me a family in Cincinnati with three or four people who have brains and agree on every issue,” Mark Mallory said. “It is not possible.”

Will any of these unusual alliances – or disagreements – over Issue 22 last beyond the Nov. 7 election? Niven, the UC professor, has his doubts.

“I would see this as a little moment of improvisational political music making,” he said.

Given the intensity of the political debates now raging over abortion, guns, civil rights, school curriculums, Donald Trump and so many other issues, the political partnerships that arose because of Issue 22 may not have much staying power.

But Brinkman said it’s possible the relationships forged during this campaign could influence some future campaign. The door is open now, he said, so there’s always a chance.

“At least we know each other’s names,” he said. “And have each other’s emails.”