ST. LOUIS — The St. Louis Reparations Commission has released its report on the racial injustices inflicted on Black Americans in the city, recommending a series of actions ranging from a public apology to cash payments.

Through a year and a half of work and nearly 30 listening sessions, the commission, established by St. Louis Mayor Tishaura Jones in late 2022, documents the injustice that’s plagued African Americans in the city for decades.

“We knew that we had to address some really deep, deep core issues in the community around trust, around transparency, around racial healing, and restorative justice,”said Will Ross, vice chair of the commission.

“It’s clear, it’s evident it was intentional over decades. I want them to see that intentionality,” Ross said. “Too many times we blame the person for the predicament they’re in, and we want to say these are these external forces, these really powerful external forces that really constrain the health of Blacks in Saint Louis.”

READ MORE: In St. Louis, a chance to preserve Black history

The recommendations included in the new report, now with the mayor and headed for the city’s Board of Aldermen, are divided into two categories: restitution-oriented and policy-oriented. It suggests, among other things, that the city adopt a formal, comprehensive history that explicitly acknowledges the racial harms into its official record. The document also includes direct cash payments to individuals who can trace their ancestry to enslaved people, to Black residents who have been disproportionately affected by systemic racism in St. Louis, and targeted cash payments to those who were subject to specific historical harms, such as former residents or direct descendants of residents of Mill Creek Valley.

In December of 2022, St. Louis Mayor Tishaura Jones signed an executive order creating a reparations commission that will be made up of nine members. Photo by St. Louis City

Ross said it’s up to city officials to decide how to move forward, but no matter what happens, it won’t be because of lack of documentation, or a lack of involvement from the community.

“They spoke and we heard them,” he said.

The mayor’s office is conducting a full analysis of the report to determine which of the commission’s recommendations could be implemented by the city, deputy director of communications Rasmus S. Jorgensen told PBS News in an email.

“However, we are pleased that some ideas, such as providing assistance for homeownership, creating more affordable housing, revitalizing neighborhoods, establishing free public wifi, and investing in public health, are already underway or have been implemented by this administration,” Jorgensen wrote, adding that the proposed direct cash payments would “significantly harm the city’s ability to provide services and invest in lifting up neighborhoods harmed by racist policies.”

These cash payments have been challenged in court elsewhere, Jorgensen added, citing the reparations program in Evanston, Illinois, which passed the first reparations law in the country and is now facing a class-action lawsuit.

The report, which begins by acknowledging the city as the ancestral home of many Native American nations, is organized using six key themes: housing and neighborhood development, education, public health, economic justice, criminal legal system reform, and cultural preservation.

Part of the commission’s work was directly with members of the community, including through open meetings. For Ross, the lived experiences of those who grew up in the Mill Creek Valley, a neighborhood bulldozed under racist urban renewal policy, retold during the meetings that remain ingrained in his memory.

“This was not historical. This was contemporary. … They were displaced and they were standing there in those rooms telling their story. It was compelling. It was moving. It was riveting,” he said.

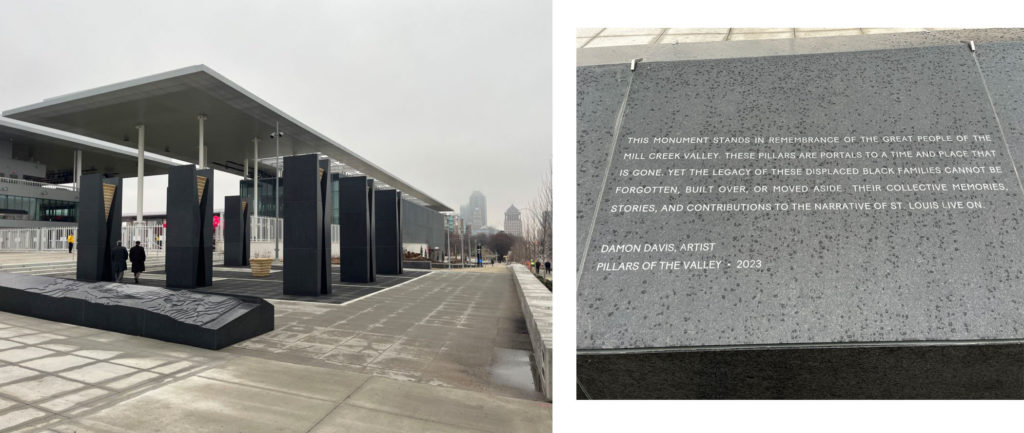

A memorial (left) made up of eight granite and limestone structures, each standing 15 feet tall — sit on the campus of the St. Louis’ new MLS stadium. An inscription (right) in the words of Damon Davis, the artist who created the memorial, is etched onto stone next to the pillars. Photos by Gabrielle Hays/PBS News

Vivian Gibson was a little girl when her family was forced from Mill Creek. She remembers the day they said goodbye to her home, a feeling she conveyed to the commission and the community during one of the meetings.

“I just really wanted to talk about my family, my family’s experience and how it impacted the future of my parents and my siblings and I,” she said.

By the late 1960s, the once bustling Mill Creek Valley where Gibson remembers playing with her siblings was unidentifiable. Some 5,600 housing units, 800 businesses and 40 churches were destroyed, spanning 54 city blocks. As one of the 20,000 people displaced and robbed of generational wealth, she wants people to know that repair is required.

“I want people to know that there needs to be some catch-up. We could never be whole if we don’t bring everyone along,” she said.

Gibson recalled the emotion in the room, as people rose from the crowd, one by one, to share their stories.

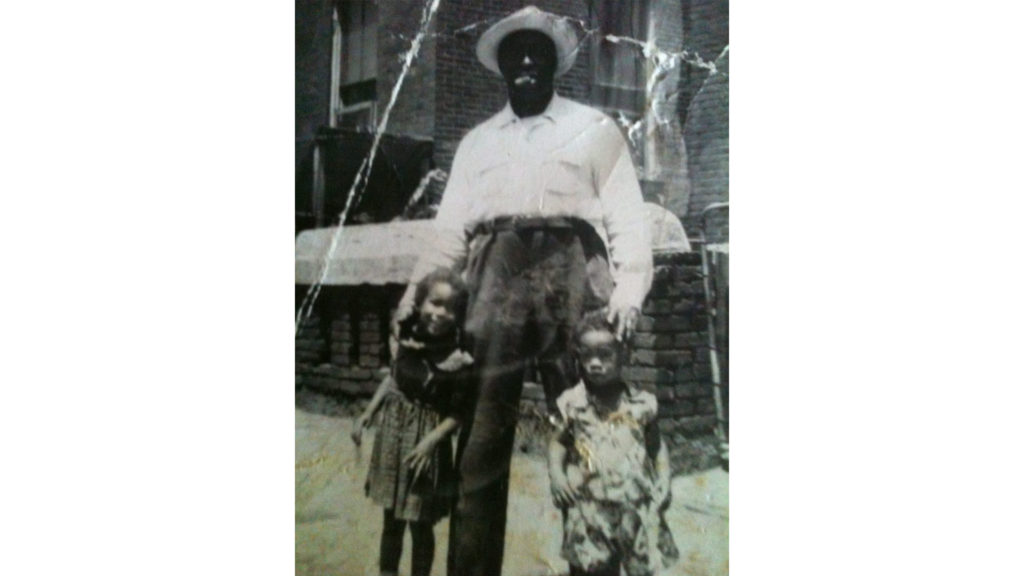

Vivian Gibson, her father, and brother Ferman stand together in 1952. Photo courtesy of Vivian Gibson

“It was in a lot of ways heart rendering to be in that experience,” she said.

The fight for reparations has become a growing movement across the country, said Justin Hansford, a law professor at Howard University and executive director of the Thurgood Marshall Civil Rights Center.

Hansford and his students have counted about 30 cities and states that have created commissions over the last few years. That list includes states like Illinois, New York and California.

Within the next three to five years, that number could swell to as many as 100 cities approaching the question of reparations, said Hansford, who is also the co-founder of the African American Redress Network, which supports groups in promoting reparations and tracks efforts across the country to remedy or offer compensation for wrongs or grievances.

Hansford serves as a member of the United Nations’ Permanent Forum on People of African Descent. It was established in 2021 as a consultative body that addresses issues related to people of African descent. The forum issued its first report last year, calling for reparations for people of African descent worldwide, saying the redresses are a “cornerstone of justice in the 21st century.”

As part of his work in St. Louis, Hansford said he tries to emphasize there are many elements of reparations that are core to the process.

“It’s not just the cash payments,” he said. “We’re thinking about policies, the changing of laws, creating financial investments into health care, housing and education to try to bridge those disparities that were created because of racism throughout the history of St Louis.”.

It’s up to each region to delve into its history and tailor its movement to fit its own experiences, he added.

Each community needs to tell its story, in its own voice, in its own words, with its own particular angle, he said. We need to have the courage and the hope to understand that we can make this a reality by focusing locally where we still have power,” he said.