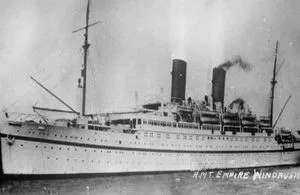

A new academic study published last week in The Lancet Psychiatry finds there is link between the Government’s hostile environment immigration policy and a subsequent decline in mental health and increase in psychological distress among the UK’s Black Caribbean population.

Image credit: UK GovernmentThe article was authored by seven doctors and professors from University College London (UCL), Imperial College London, and the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). It is an open access article and is freely available online here.

Image credit: UK GovernmentThe article was authored by seven doctors and professors from University College London (UCL), Imperial College London, and the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). It is an open access article and is freely available online here.

Explaining the purpose of their study, the authors said: “In this study, we investigated whether the effect of the hostile environment policy caused changes in the mental ill health of people from minoritised ethnic backgrounds in the UK. We specifically hypothesised that people from Black Caribbean backgrounds would have had worse mental ill health than people of White ethnicity following the introduction of the Immigration Act of 2014, and again after media coverage of the Windrush scandal commenced in 2017, because they were particularly targeted by the hostile environment policy and its aftermath, as encapsulated by the Windrush scandal,”

Detailed and lengthy analysis was undertaken for the study of a cohort of over 58,000 participants from ethnicity groups of interest who responded to the UK Household Longitudinal Study (UKHLS). UKHLS is based at the University of Essex and is the largest longitudinal household panel study of its kind.

In the article in The Lancet Psychiatry, the authors find that people of Black Caribbean heritage in the UK experienced an increase in psychological distress after 2014, which was attributed to the Immigration Act 2014 and the Windrush scandal. Similar effects were not found for other ethnic groups.

The authors stated: “We found evidence that the UK Government’s hostile environment policy and subsequent media coverage of the Windrush scandal caused people of Black Caribbean ethnicities living in the UK to experience greater psychological distress relative to the White ethnicity group, in line with our hypothesis. This mental health inequality persisted for several years after these events. In first-generation Black Caribbean migrants, higher levels of psychological distress occurred immediately after the introduction of the Immigration Act 2014, but those did not rise further when the Windrush scandal emerged in the popular press. In UK-born people of Black Caribbean heritage, greater psychological distress occurred in the aftermath of the 2017 Windrush scandal media coverage, and this was the largest single change in mental health observed in our study.”

According to the article, these findings are consistent with evidence from previous research that media exposure to distressing news concerning people from the same minoritised ethnic background is associated with mental ill health.

Dr Annie Jeffery, lead author of the study, said the mental health impacts may have stemmed from the direct impacts of threats to people’s homes and livelihoods, but could also have resulted from a wider, pervasive sense of racial injustice and bias faced by a group already experiencing systemic and sometimes institutionalised racism and discrimination.

As a result of the findings, senior author Professor James Kirkbride stressed that policymakers should consider people’s mental health when deciding immigration policies.

Kirkbride said: “Our findings show that government policies can produce, maintain and exacerbate systemic inequities in mental health. Policymakers should consider the mental health impact of immigration policies, as they can impact not only prospective immigrants or people without leave to remain, but also those who are already settled legally in the country, and thus they should design them to minimise all harms including mental health inequalities.”