Clinical Relevance: Studies show that Black patients have better health outcomes under Black doctors

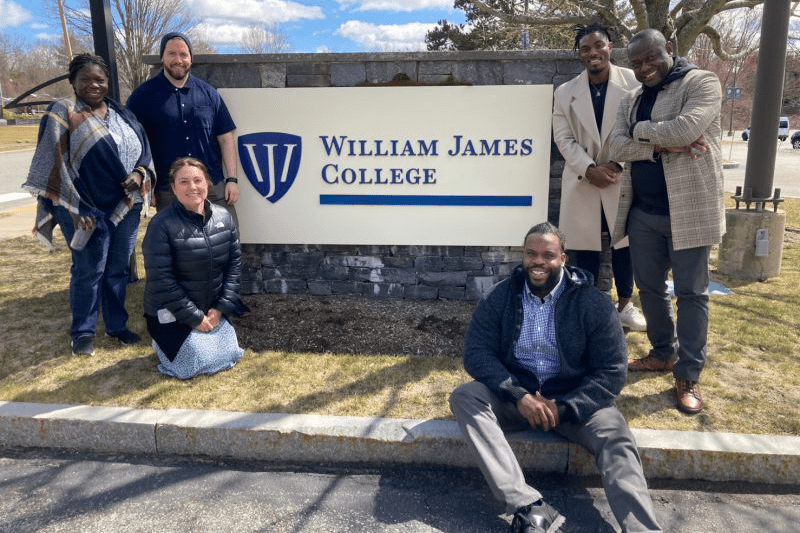

- Joan Axelrod, Director of ARC at William James College, is leading efforts to diversify the behavioral health workforce.

- The college offers innovative programs, scholarships, and community engagement to address mental health disparities.

- Increasing diversity in mental health education aims to provide better care for underserved communities.

They call her Joan of ARC.

She’s actually Joan Axelrod, director of the Academic Resource Center (ARC) at William James College, a private four-year college in Newton, Massachusetts that focuses on experiential and graduate education for the behavioral health professions.

As her legendary namesake did for the people of France, this Joan is a savior to the approximately 900 students at this private college, which offers graduate and certificate programs in psychology. The students come here for guidance on everything from where to find a tutor to how to write a research paper. Many are young people of color who are participating in one of the programs at William James designed to train a more diverse cadre of mental health professionals.

“They are so committed about giving back to their communities,” said Axelrod, standing in front of a bulletin board by her glass-paned office.

Her students are trying to make a difference.

“My community needs this help,” Axelrod said. “I hear that a lot.”

Diversifying Mental Health

William James College is helping its students make an impact in an area of health inequality that is not widely talked about. While we have heard often about the disproportionate rates of diabetes, hypertension, COVID, heart disease and other physiological illnesses in minority communities, mental health is also part of these disparities.

The Black Physician Experience

Dr. Russell Ledet Says, “I Just Need You to See Me For Me”

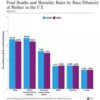

And there’s at least one compelling reason for that.

“Psychology is a field that is primarily white,” said Gemima St. Louis, vice president for workforce initiatives and specialty training at the college. “That lack of diversity certainly helps create significant disparities when it comes to people from minority backgrounds finding clinicians who understand their cultural backgrounds or have the linguistic capacity to meet their mental health needs.”

Lack of diversity is indeed striking. According to a 2015 report from the American Psychological Association, 86 percent of U.S. psychologists are white. In 2019, the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that close to 70 percent of U.S. social workers and 88 percent of mental health counselors were also white.

William James College, founded in 1974 and named after the father of American psychology, decided to address this issue.

“I think as an institution we made a conscious effort to stop talking about the problem, and take action,” said St. Louis. Specifically, the college adopted a new mission statement: To help build “a well-trained and diverse behavioral health workforce that can deliver culturally responsive care to children and adolescents, and promote inclusive practices in high-need schools.”

Expanding Efforts

Earlier this year, a major grant recognized their ambitious plan. Over the next five years, the $5.9 million the DOE grant will provide scholarships and stipends to recruit and retain graduate students from underserved communities (defined by the college as first-generation students; individuals with disabilities; ethnic, linguistic, and racial minority groups; and LGBTQ+ groups) who are committed to working as school psychologists and behavioral health counselors in high-need public school districts in Massachusetts.

Other programs have also attracted funding. “Our tagline is ‘from high school to grad school, building a diverse pipeline,’” said St. Louis. “For folks who only have a GED, we now have a community health workers program, in which we place a cohort of students in jobs available with our partner organizations. These are full time positions with benefits, but at the same time, they’re enrolled in an 80-hour certificate program for community health mental workers. They get mentorship, they get career guidance.”

And they get college credits and a stipend—addressing what Saint Louis calls two of the primary barriers keeping young people of color from pursuing a career in mental health.

“There are so many smart, talented, compassionate folks, but when you talk to them, and say ‘have you considered getting your bachelor or masters?’ they say, ‘no I don’t have the money and I don’t have time.’ We needed to fix the money and the time problem.”

Leading the Way

Yohana Beraki, a doctoral student in the clinical psychology program at William James College, is ready to help lead the charge. Born in Los Angeles, raised in Indiana, she majored in psychology at Purdue University as an undergraduate, then earned her master’s degree in psychology at Boston University.

As part of her doctoral program at William James—which emphasizes “experiential” education—Beraki has trained in a variety of clinical settings in the Greater Boston area that serve children and their families, including HRI Hospital, The Baker Center for Children and Families, Lynn Community Health Center, Prime Behavioral Health, and McLean Hospital. She lists her clinical and research interests as providing high-quality mental health care to underserved communities and creating adaptations to existing evidence-based treatments in order to provide culturally sensitive, inclusive treatment.

“I want to help increase the number of clinicians of color,” said Beraki, 27. “I want to bring more representation and to help serve communities that look like me.”

The lack of role models is another factor complicating the already-worrisome healthcare disparities in the US. Having a more diverse workforce in mental health would go a long way towards helping narrow that gap.

Better Outcomes

“It’s been proven that Black patients have better health outcomes under Black doctors,” said Mauvareen Beverley, MD, author of the upcoming book, Nine Simple Solutions to Achieve Health Equity: A Guide for Physicians and Patients. “I would think it would be the same with mental health outcomes. Because that doctor or clinician understands some of the trauma that Black individuals have gone through.”

The disparity of the practitioners is compounded by a disdain for the practice. Cultural taboos and stigmas make it less likely that people in these communities will even seek out a mental health professional, much less, find a clinician that looks or speaks like they do.

“When underserved groups don’t see health care professionals who look like them or understand their unique experiences and needs, the system can be hard to navigate and it can be difficult to build trust, resulting in less engagement in care,” wrote Joneigh Khaldun, MD and Cara McNulty in a US News & World Report opinion piece last November.

Beverley wondered if this supposed stigma is less about deeply-felt attitudes than it is about a dearth of availability. “I don’t really buy this notion that the Black population don’t want access to mental health care because they don’t trust it or understand it,” said Beverley, who has served in various clinical and administrative positions in the New York City hospital system. “My belief is that you can’t say they don’t want it if you don’t offer it.”

She recalled her experience at New York’s Queens Hospital, when she helped organize the first support group for adult patients with sickle cell disease. “We realized that no family counseling was being offered,” she said. Nor were most of those in the support group referred for depression screening or to see a mental health specialist. “So we brought in a psychologist as part of the team and I know it helped many of the families that were under our care,” she said. “If we hadn’t offered it to them, they probably would not have sought out that kind of care. It has to be included in conversations with patients and made available.”

Hope for the Future

The graduates of William James College’s programs appear ready to have that conversation; ready to help ensure that better mental health care is available to underserved communities, particularly in Massachusetts.

Changing both the workforce’s complexion and these deeply-ingrained beliefs is a daunting task. But it wouldn’t require a miracle. Just ask Joan of ARC. “I love the collective spirit among our students and faculty about creating a more equitable healthcare system for underserved communities,” Axelrod said. “To see people so committed to this cause just warms my heart.”