For many today, the difficulty of cross-country travel lies with the high cost of gas and navigating confusing roadways, with little thought given to having access to a bed for the night or a bathroom to relieve yourself when the pressing need arises. The Negro Motorist Green Book, a new exhibit on display at the Holocaust Museum Houston through November 26, serves as a poignant reminder that not so long ago, the simple act of traveling was fraught with danger and discrimination for African Americans in the United States.

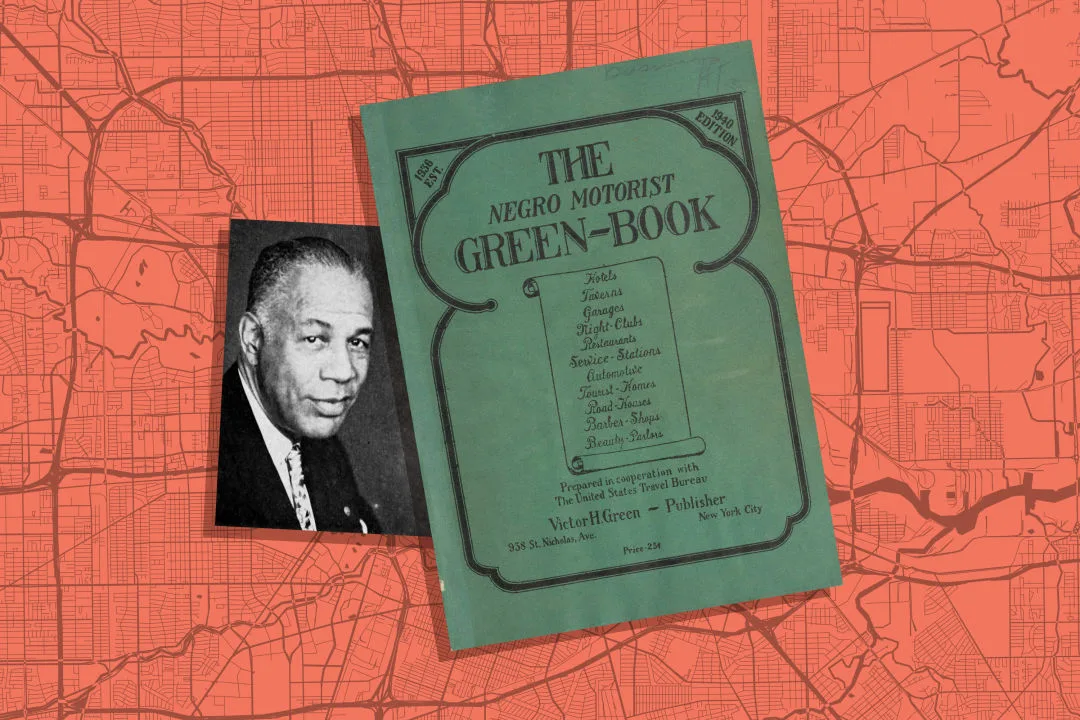

This exhibit invites visitors to step back in time and immerse themselves in a world where getting around the country by car required careful planning, vigilance, and an intimate knowledge of safe havens for African American travelers. In 1936, postal employee and travel writer Victor Hugo Green began writing an annual guide to businesses that accepted Black customers. The Green Book became a lifeline for navigating a segregated country.

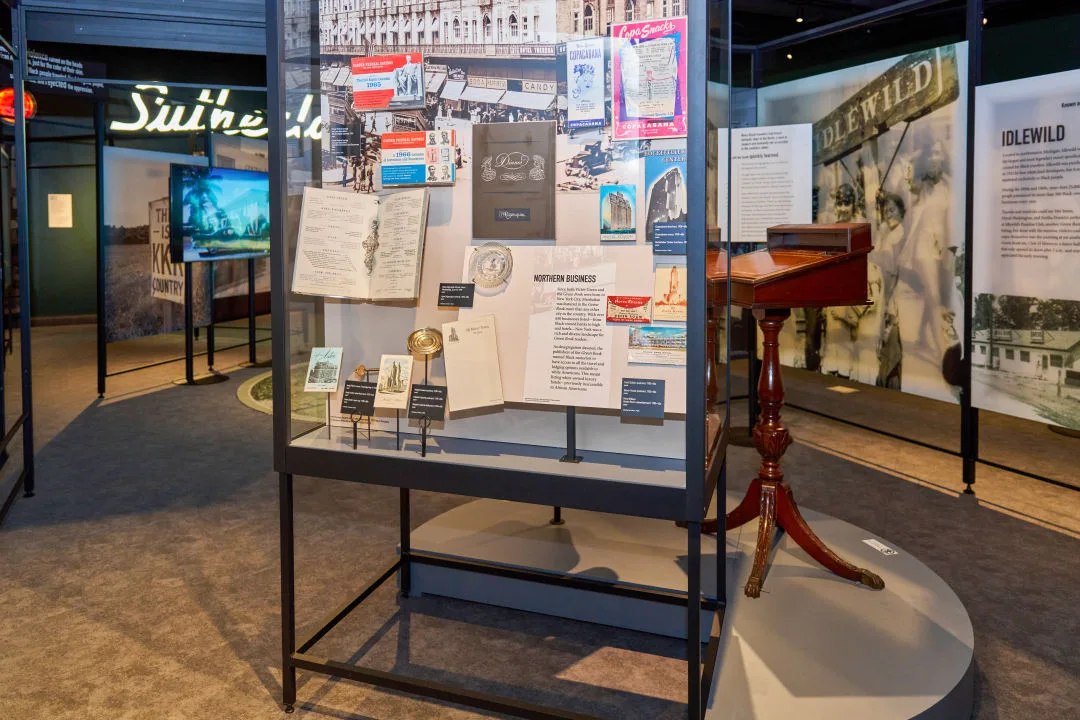

Curated by the Smithsonian as a 13-city showcase, The Negro Motorist Green Book exhibit is a collection of artifacts and imagery that takes visitors on a journey from the mid- to late 1930s up until the late 1960s, capturing a pivotal period in American history. Named after Green’s guide, the interactive exhibit allows visitors to virtually journey from Chicago to the South, making choices along the way that affect their experience while providing a deeper understanding of the decision-making process and challenges faced by travelers during this era.

The Negro Motorist Green Book began its tour around the country in Memphis, Tennessee, in October 2021, and will have its last stop at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library in Washington, DC, starting in October 2024. The local exhibits reflect each city’s unique Green Book history, and the heart of this compelling narrative beats strongly right here in Houston.

“We learned that the Texas Historical Commission had uncovered 115 locations in Houston alone,” says Alex Hampton, the changing exhibitions manager at the Holocaust Museum Houston. “It is important to remember that 13 of those sites in that 115 were very prominent in the Green Book, and eight of them are still with us today.”

One such site is the Eldorado Ballroom, a historic venue in Third Ward that hosted legendary musicians like B.B. King, Count Basie, and Etta James. The “Rado” was not only a safe haven for Black Houstonians and visitors alike, but also a space to enjoy music, dance, and a sense of community in a segregated society. Some of the other locations that remain to this day include Beau Brummel Barbershop, Ralston Drugs, and Martin’s Beauty Parlor—all originally on Lyons Avenue in Fifth Ward—and the Houston College for Negroes, which we now know as Texas Southern University.

As a complement to the exhibit, a free lecture by Dr. Lindsay Gary, author of The New Red Book: A Guide to 50 of Houston’s Black Historical and Cultural Sites, will be held on October 10. Gary will discuss the research methods and practices used to create her book, as well as highlight the role texts have played in the past and can play the future in preserving the legacy of Black historical and cultural sites.

Beyond the guide’s ties to Houston, the exhibit underscores a shared history of discrimination and resilience among African American travelers and those in the Jewish community (the main focus of the Holocaust museum), making it all the more evident that this historical narrative is not an isolated one.

“We were able to obtain several brochures that outwardly are either antisemitic in nature or racist in nature that were targeted during this time,” Hampton says. “We were really just wanting to show that there is a parallel story here and there is a reason that these histories go hand-in-hand when it comes to travel in early America.”

Curating an exhibit as profound and historically significant as The Negro Motorist Green Book presented its own set of unique challenges. Bringing to life a bygone era filled with the struggles and triumphs of Black travelers required meticulous research, collaboration, and a deep understanding of the cultural and historical context.

“We wanted to make sure that everything we did was with respect to the community,” Hampton explains, adding that the team consulted with historically Black churches and organizations like Jack and Jill, the Divine Nine, and more. “We really turned to them for how should we go about marketing this? And how do we make sure that we’re reaching the community that we need to reach?”

Hampton recognizes the importance of community involvement in curating an exhibit that would do justice to the historical significance of the Green Book, as this narrative isn’t just a distant memory but a lived experience for many African Americans.