Six months after the state Legislature passed the bill for a reparations commission, Gov. Hochul signed it into law at the New York Historical Society on the Upper West Side on Tuesday.

This comes less than two weeks after state Sen. James Sanders Jr. (D-South Ozone Park) led a symposium at York College in Jamaica, about his bill, S1163A, and the Assembly version, A7691.

The state Senate bill and its counterpart made it through both chambers in June with votes of 41-21 and 106-41, respectively.

The law says that a state community commission is to be formed to study the impact of reparations and create remedies for African Americans who are descendants of slaves. Once an analysis into the generational impacts of slavery and segregation in New York is completed, the commission would formulate an approach to compensate for the damages.

“I have nine stitches in my head from three incidences of where I just didn’t know my place,” Sanders said sarcastically at the bill signing. “I still don’t know my place, but I don’t want any more.”

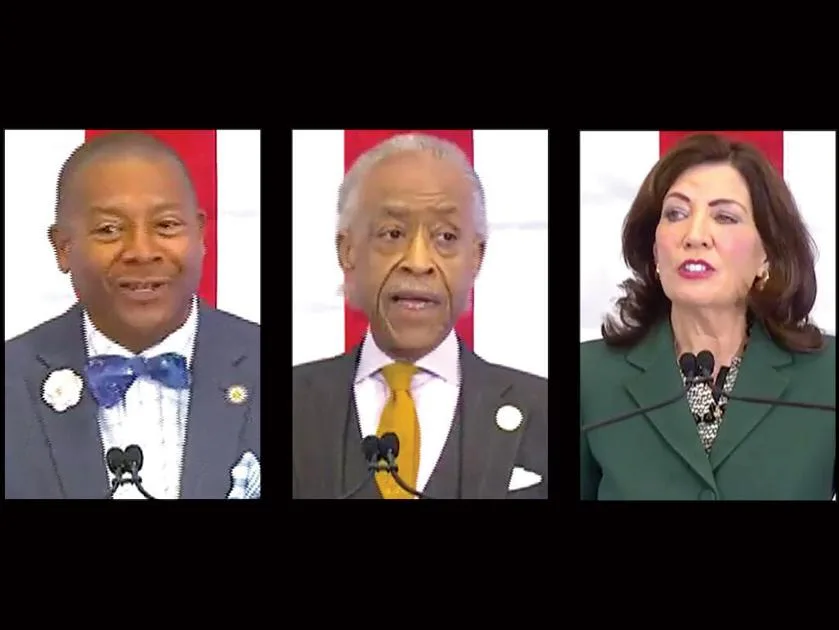

Sanders thanked God and then Hochul, along with other elected officials and the Rev. Al Sharpton, who have been advocating for the legislation.

“I’d be remiss if I did not say that I’m here because of my sharecropper father and my domestic worker mother,” Sanders said. “We fled a tyranny, we fled a terror, we fled an unjust government that was working on terrorism and I am an immigrant — I’m a first-generation — we fled the South. We fled all of those folks who were doing horrible things to us.”

He later dedicated his speech to the people of Seneca Village, a mixed-race neighborhood of predominantly free Black people and immigrants of Irish and German descent who lived and prayed together before the town was destroyed by wealthy elites to make way for Central Park, a green space with the grandeur of those in Europe, according to CBS News.

The city used eminent domain and said it was using the land to build park space that would combat unhealthy urban conditions, according to the Central Park Conservancy.

There were 225 residents, two-thirds Black in 1855, and it was one of the few places where African Americans could escape racial discrimination in Manhattan.

African Americans and the AME Zion Church bought land on what is now Central Park as far back as 1825, and by the 1830s, there were at least 10 homes on some of the 200 lots. By the 1850s, the village comprised 50 homes, three churches, burial grounds and a school for Black students. Because of its remote location, it was a refuge for Black people. Of the 100 Black New Yorkers who were eligible to vote in 1845, 10 lived in Seneca Village. In 1857, approximately 1,600 people were displaced, but compensated for their homes, but many argued their land was being undervalued, according to the conservancy.

“It was 1853, the New York State Legislature passed a bill, saying they were going to put Central Park up there,” Sanders said. “The Legislature said, ‘we are going to get rid of those people.’”

Sanders said the residents of Seneca Village were middle-class people.

“They had more Black homeownership,” Sanders continued. “Imagine if we had let that happen. Imagine if we let that happen in America. They were driven out, forced to go elsewhere and were never paid what they should have gotten for theirs. They were also an integrated community. They had an integrated church that had a little bit of everybody in 1853. They were more integrated than most churches are here today on Sunday morning.”

The people of New York sit in the shadows of Seneca Village, he added.

The senator said he could see the “new New York.”

“It’s a place where the color of your skin is no more important than the color of your eyes,” he said. “It’s a place of where you will be judged by the content of character, not your melanin.”

Sharpton thanked Hochul for being courageous in signing the bill.

“I know her political advisors told her it was too risky, but she did it because it was right,” the reverend said. “She said, ‘It’s going to be unpopular to some, but I’m going to do what is right.’ Some of the media is going to act like she gave us a billion dollars, but that is not what this is. This is the beginning of healing the scars. We can never be one state unless we heal scars.”

While the ancestors of others were on Wall Street, Black folks were being sold on boxes like soap, continued the reverend.

“Nobody sponsored us, we had to fight …” said Sharpton. “The battle for Civil Rights was not below the Mason Dixon line. The largest port of slave trade was in Charleston, North Carolina and Wall Street, New York … This starts the process of taking the veil off of Northern inequality.”

Hochul said there was a slave market on Wall Street for more than a century.

“People bought and sold people with careless disregard,” she said. “Even though it closed when slavery was abolished in New York in 1827, our state remained a dominant player in the illegal slave trade … Former slaves, and their children, and their childrens’ children across our nation have been haunted for generations by racism and disenfranchisement. Millions of people, even though free on a piece of paper, were still trapped by Jim Crow.”

Blacks and brown people were stripped of their rights to participate in democracy, stalked by the Klan, impacted by real estate redlining and hit with other forms of economic repression.

“All were designed to keep Black and brown Americans from reaching that first rung on that ladder to success and many where kicked down when they finally got there,” Hochul said. “It’s an ugly truth, but as patriots, as Frederick Douglass said, ‘We must bear witness.’”

Sanders said that Dec. 19 will be etched in the annals of New York State history.

“This commission marks a crucial step towards acknowledging that pain, understanding its present consequences, and finally taking action to build a more equitable future,” he said.