During summer 2020, at the height of the pandemic, my family moved across the country from a small town in upstate New York to Saint Paul, the capital of Minnesota. With my school, Central High, completely remote for most of my first year in Saint Paul, I rarely left my house except for the occasional bike ride through the unknown streets of the city. As I rode, I started to understand the geographical divides that were between different parts of the city, formed along roads, on either side of hills, or by the river. These divisions were accentuated by the visible barrier of the I-94 highway, which I learned at school, was one block away from Central. But at the start, I didn’t think much about the highway. It seemed like an annoying yet unthreatening fixture of the city, useful when I wanted to get somewhere quickly or leave the city altogether.

Before moving, when I lived in a 6,000-person town, I thought I understood the issues with car-centered infrastructure for cities across the country. I knew about their connection with suburbanization and urban sprawl, their contribution to loud, congested, and un-walkable cities, and the extensive government investment in cars which diverted funds from public transportation and led to endless strip malls and massive parking lots. But as I learned in Saint Paul, the damage goes well beyond simply the aesthetic and practical effects on cities. The negative ramifications of federal policy are felt much more disproportionately by African Americans and communities of color, as is so often the case in the U.S.

Throughout the mid-1900s there was a massive federally funded initiative, kicked off by the Federal Highway Act of 1938, aimed at creating the “world’s most advanced network of highways.” This infrastructure project was pitched as a way to facilitate easy transportation into and out of cities and, in doing so, provide many new jobs to those who were put out of work during the Great Depression. However, the inevitable consequences of this investment have affected communities to this day.

In large part, the interstate program was funded by and prioritized the interests of lobbyists and special interest groups. Often, residents pushed back, and sometimes the government even agreed to cancel plans for highway construction if the residents put up enough of a fight. Almost always, the communities that were able to divert highway construction were white, and the diversion ended up on a new route through neighborhoods that would not be able to as easily defend themselves and gain news coverage. One of the most devastating examples of this process occurred in New Orleans after the passage of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, which devoted billions of dollars to fund highway construction across the country. Residents of the predominantly white French Quarter vehemently resisted a proposed highway through their neighborhood, while those living in Tremé, a center for Black music and culture, were barely even aware that their community was also being targeted by the interstate program. When the government, under eminent domain, seized Claiborne Avenue, which had once been a vibrant main street in the center of the neighborhood, there was nothing Tremé residents could do. The highway built in its place, I-10, cutting through the heart of Tremé, displaced businesses and homes and forced residents to face the noise and pollution of an interstate highway practically in their backyard.

The story in Saint Paul follows national patterns. The same Federal Highway Act which led to the devastation of Tremé initiated the construction of I-94, which was built a block away from Central High School and sliced the Rondo neighborhood in half. Like Tremé, Rondo was a culturally and economically thriving community with a history of political activism, and before I-94, was home to 80 percent of the city’s African-American population. According to Reconnect Rondo 700 homes and 300 businesses were destroyed to make way for the highway, which left a visible scar on the landscape of Rondo, a constant reminder of the generational trauma caused by the highway’s construction.

Practically every city in the US has seen a highway built through its center, and almost always, it was African-American communities and, more broadly, communities of color torn apart. I have wondered while living at Swarthmore if Philadelphia has a similar history. I knew highways encircle the city, and several of them were also enabled by the destruction of neighborhoods of color. Roosevelt Boulevard, built as an extension of I-76, cut through the neighborhood of Nicetown, which is nearly 90 percent Black. As the New York Times reported, funds from the 1956 Federal-Aid Highway Act, the Vine Street Expressway was built through the Chinatown neighborhood, parts of which, once busy and thriving, now “feel more industrial, less vibrant.”

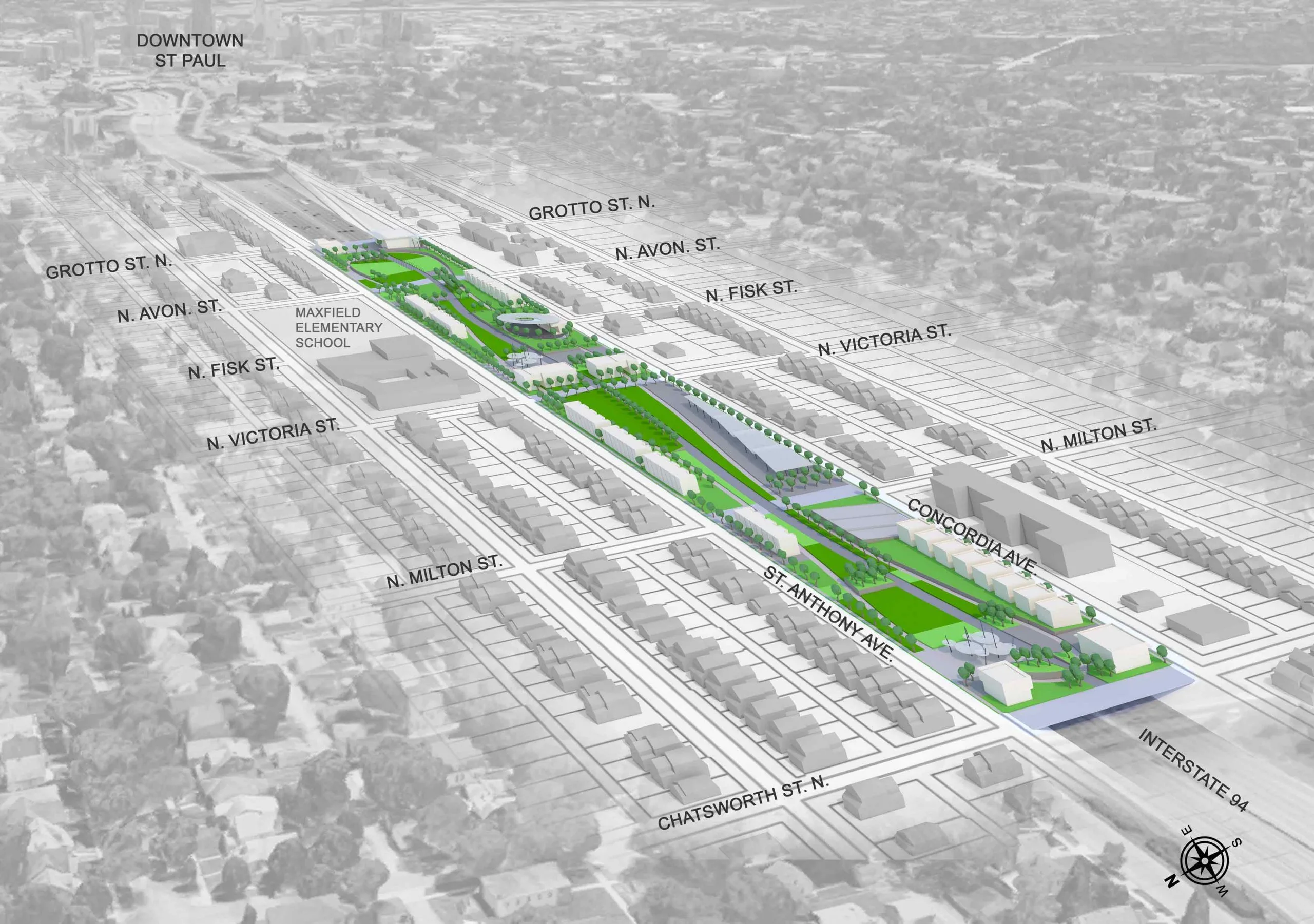

Ever since the highway construction, residents have worked to remake the physical landscape and in turn, revitalize their neighborhoods. In Saint Paul, an organization called Reconnect Rondo, based in and led by residents of Rondo, is setting a national model for how to give the communities control over how they are shaped in the future. Reconnect Rondo has proposed the construction of a mile-long land bridge over I-94, uniting the two halves of Rondo that were divided by the highway. In Tremé, the Claiborne Avenue Alliance has a similar goal of reconnecting and reigniting the neighborhood by completely removing the section of the highway that replaced Claiborne Avenue. As many in these organizations will say, significant infrastructural changes have to be followed up with much broader initiatives aimed at public transportation investment, walkable cities, increased mixed-use zoning, and addressing the legacy of racism that has been physically built into so many of our urban areas. Learning more about Rondo and places like it can help us think historically about the politics of our physical environment and understand what can and should be done moving forward.