To Amy Stelly and other residents of New Orleans’ Tremé neighborhood, the elevated stretch of Interstate 10 built alongside their homes more than a half-century ago is known as “The Monster.”

The highway, called the Claiborne Expressway, has become a vital passageway, allowing commuters and commerce traffic to cross over one of the city’s most historic neighborhoods into the Central Business District.

But to Stelly, a designer, teacher and New Orleans native, the expressway is a concrete behemoth that tore through Tremé – the nation’s oldest Black community and the birthplace of jazz music – destroying its economy, and forcing businesses and residents to leave.

New Orleans’ Claiborne Avenue Expressway cuts through one of the oldest African American communities in the country.

ABC News

“It’s huge, it’s dirty, it’s loud…it just dominates the neighborhood, and it gives nothing back,” said Amy Stelly, who still lives in the house she grew up in about a block from the expressway.

After 55 years of constant traffic, The Monster has left yet another ominous legacy.

Environmental Protection Agency data show the mostly Black Tremé residents are being exposed to a daily dose of toxic chemicals such as benzene, formaldehyde and diesel particles that come from vehicles on the expressway.

The toxins put residents living in the neighborhood over a 70-year lifespan more at risk for respiratory illnesses and cancer from traffic pollution, according to the EPA’s 2014 National Air Toxic Assessment (NATA).

The situation in New Orleans is not an isolated case.

More than 49 million Americans live within a mile of a highway and face startling health risks from traffic pollution, according to an ABC News data analysis done in collaboration with ABC-owned television stations.

The ABC News analysis included the NATA data and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) PLACES dataset, which estimates the prevalence of chronic diseases like asthma.

The CDC data show nearly 11,000 census tract neighborhoods across the U.S. are within a mile of an interstate highway or major freeway where asthma rates among residents were above 2017 national averages of 8.4% for children and 7.7% for adults.

The NATA analysis found that constant commuter traffic from the nation’s interstate highways is also contributing to toxic air pollution in the remnants of those nearby neighborhoods that were carved up and torn apart when the freeways were built nearly a half-century ago.

NATA data used in the ABC News analysis measures the amount of airborne toxins known to cause certain types of cancer and respiratory illnesses that are generated by “onroad sources,” or vehicle traffic, in U.S. census tracts.

The toxins measured include known cancer-causing chemicals such as benzene and formaldehyde, and other hydrocarbons – ingredients in gasoline and other engine fuel products that are emitted into the air through vehicle exhaust.

NATA calculates the risk of developing those illnesses for a person living in a tract over a 70-year lifespan.

While many factors – diet, genetics, access to healthcare, language barriers and behavior – can contribute to higher-than-average health problems, experts say traffic pollution is a known health hazard.

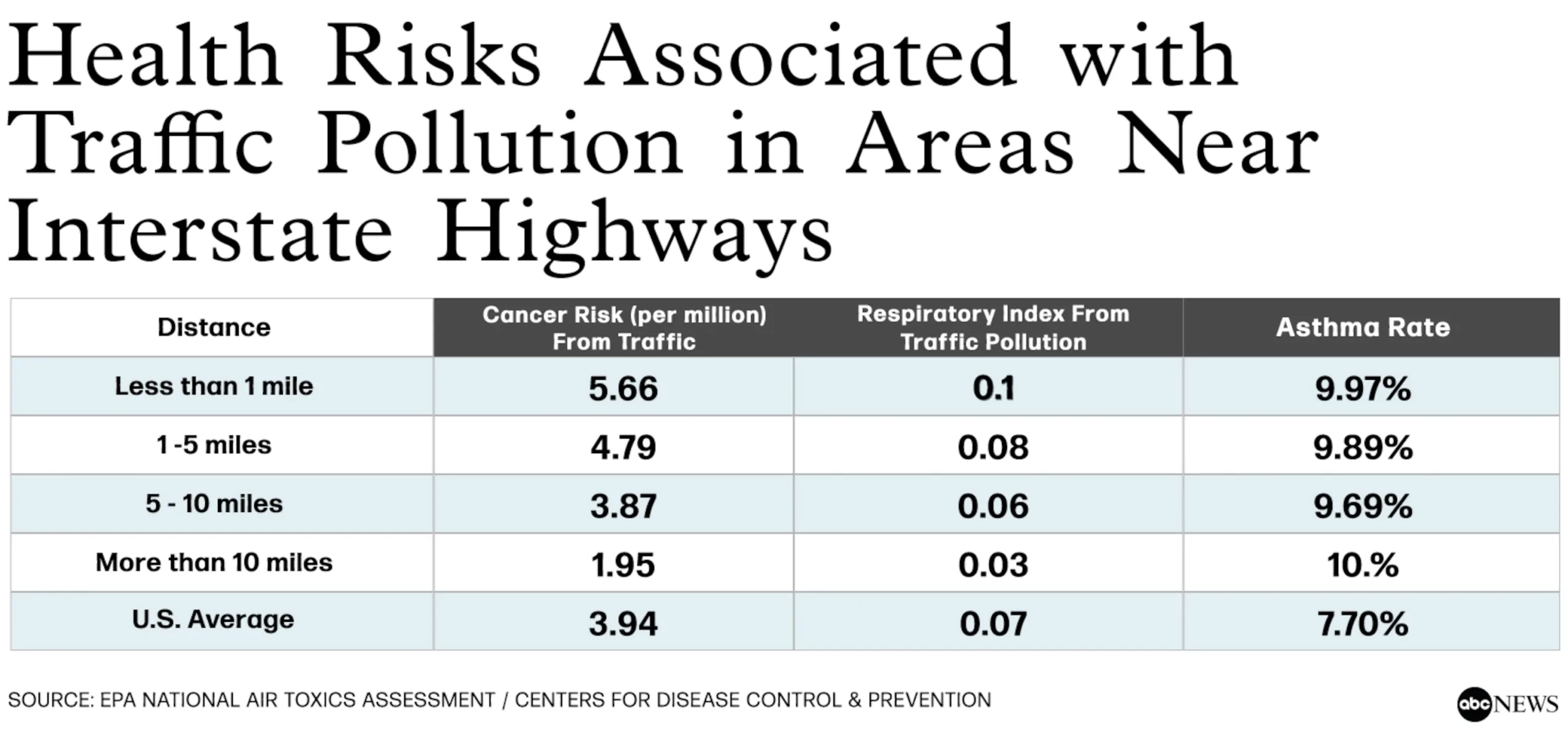

The NATA data found the lifetime risk of developing a respiratory illness like asthma or Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) from toxins associated with traffic is 3.4 times higher in tracts less than a mile from a highway than in areas more than 10 miles away.

The overall lifetime cancer risk (per million) from toxins associated with traffic is 2.9 times higher when comparing neighborhoods closest and farthest away from a highway, according to the NATA.

Health Risks from Living Near an Interstate Highway

EPA National Air Toxics Assessment / Centers For Disease Control & Prevention

“These highways are not just something that happened in the past,” said Dr. Adrienne Katner a program director at Louisiana State University’s School of Public Health. “They are ongoing issues. They are causing an ongoing environmental health problem in these communities.”

An ongoing environmental health problem that has racial undertones, according to the data.

The ABC News analysis found that about half of the 49 million people who live in tracts less than a mile from a major highway are nonwhite. Only 29% of 84 million people who live more than 10 miles from a highway are nonwhite. Nationwide, 2021 census data shows about 41.1% of the 333.3 million U.S. residents are nonwhite.

“America is segregated, and so is pollution,” said Dr. Robert Bullard, a distinguished professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University, who is called the “father of environmental justice” for his groundbreaking research on environmental inequities.

“Monuments to racism”

America’s history of ramming highways through mostly low-income neighborhoods largely populated by people of color began with the birth of the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956.

Researchers and civil rights advocates say that the Highway Act ushered in a generation of “urban renewal” – expansive, federally funded projects by local governments that razed neighborhoods, particularly those adjacent to downtown business districts, where there was real estate interest among developers and corporations.

Those urban renewal efforts became the U.S. Interstate Highway System, more than 48,000 miles of roadway that was funded by billions of federal tax dollars.

The highway system not only created a means of cross-county vehicle travel, but also proved to be a boon for rural and suburban communities across the nation.

By the 1950s, highways were being built across America, establishing vital trade routes and connecting booming suburbia with downtown business centers in cities across the nation.

Wealthier residents fled to the suburbs and used the highways to commute to their jobs and other amenities in nearby cities.

At the same time, many of those new highways tore through entire neighborhoods, displacing millions of property owners and cutting into the tax base in some cities. Others wrapped around neighborhoods, creating concrete buffers of segregation.

Along with blocks of homes, these neighborhoods lost churches, parks and small businesses – vital institutions in often already economically depressed areas.

Views of Claiborne Avenue 1966 (left) and 1968 (right).

Claiborne Avenue Design Team/Waggonner & Ball Architects

While many white residents were forced out of their neighborhoods during highway construction, much of the displacement burden fell on people of color.

Census data shows that in 1960, when highway projects began to escalate, about 72% of all nonwhite residents lived in an urban area, compared to 52.7% of all white residents.

Barred from moving into segregated white neighborhoods, those displaced residents were often forced to crowd into neighborhoods nearest the highways that were already struggling with poverty and decay, or into segregated public housing.

“Urban highways are monuments to racism,” said Stelly, co-founder of the Claiborne Avenue Alliance, a coalition of residents, business owners and professionals dedicated to the restoration of the Claiborne Corridor.

Amy Stelly is among the most prominent advocates for the Claiborne Avenue Expressway to be removed.

Evan Simon/ABC News

“When you deliberately put these pieces of infrastructure into Black neighborhoods without regard for what happens to the people who are impacted by it…it’s a monument to racism.”

For the remnants of residents left to live – and those residents now living – in the shadow of highways, EPA and academic studies show the interstate system has created daily moats of high-speed traffic, polluted air and aggravated health risks.

High-risk highway neighborhoods

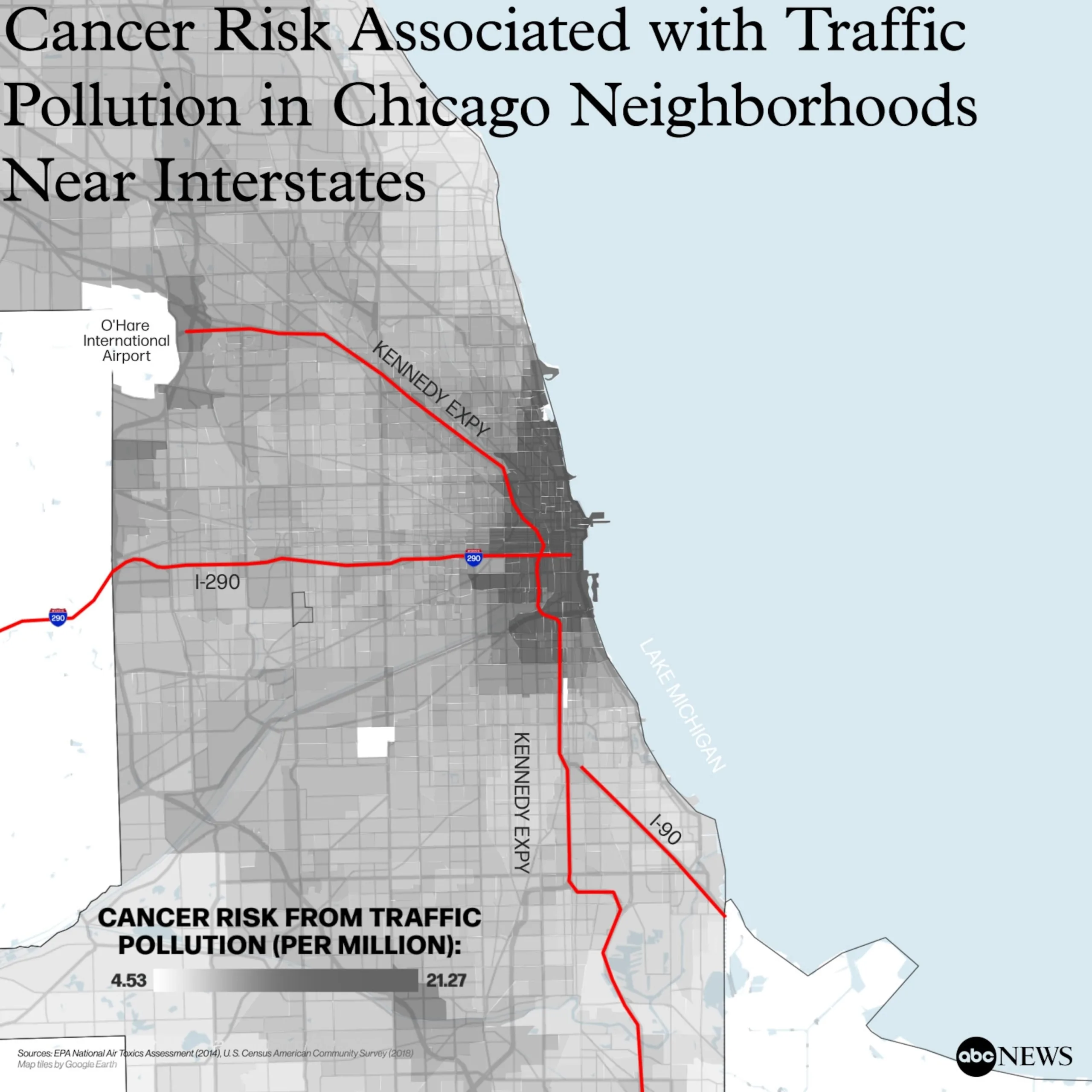

ABC News’ data analysis shows the nation’s top five census tract neighborhoods for cancer risk and respiratory problems are all in Chicago, within a mile of the city’s three major thoroughfares – I-290, I-94 and the John F. Kennedy Expressway.

The top neighborhoods are among 99 tracts located in the shadow of those three interstates, where 53.8% of the residents are nonwhite.

In those five tracts alone, the lifetime cancer risk associated with toxins from traffic pollution averages 20.56 per million – five times the national average of 3.94 per million. The risk averages 11.6 per million in all the tracts around the three interstates.

The respiratory hazard index is a composite score that measures the probability of traffic pollutants causing respiratory illnesses. The higher the index, the greater the risk of developing respiratory illnesses, with indexes above 1 representing an above-normal risk over a 70-year lifespan.

Indexes average .503 in the top five Chicago tract neighborhoods – below the above-normal hazard index, but 7½ times the national average of .0654. The asthma rate, or the percent of adults with diagnosed asthma conditions in the five Chicago tracts is 8.12%, also above the 7.7% national average.

Cancer risk associated with traffic pollution in Chicago neighborhoods near interstates

EPA NATA (2014), U.S. Census American Community Survey (2018)

In the Bronx borough of New York City, data show 45 census tract neighborhoods within a mile of I-95 with double-digit asthma rates. One of the tracts has an asthma rate of 20.6% — highest in the U.S., and 2½ times the national rate. About 89% of the residents in the Bronx tracts are nonwhite.

Those Bronx tract neighborhoods, part of an area some health officials call “asthma alley,” have a combined respiratory hazard index from traffic pollution of .229 – 3½ times the national average. The cancer risk is 11 per million, more than 2½ times the national average.

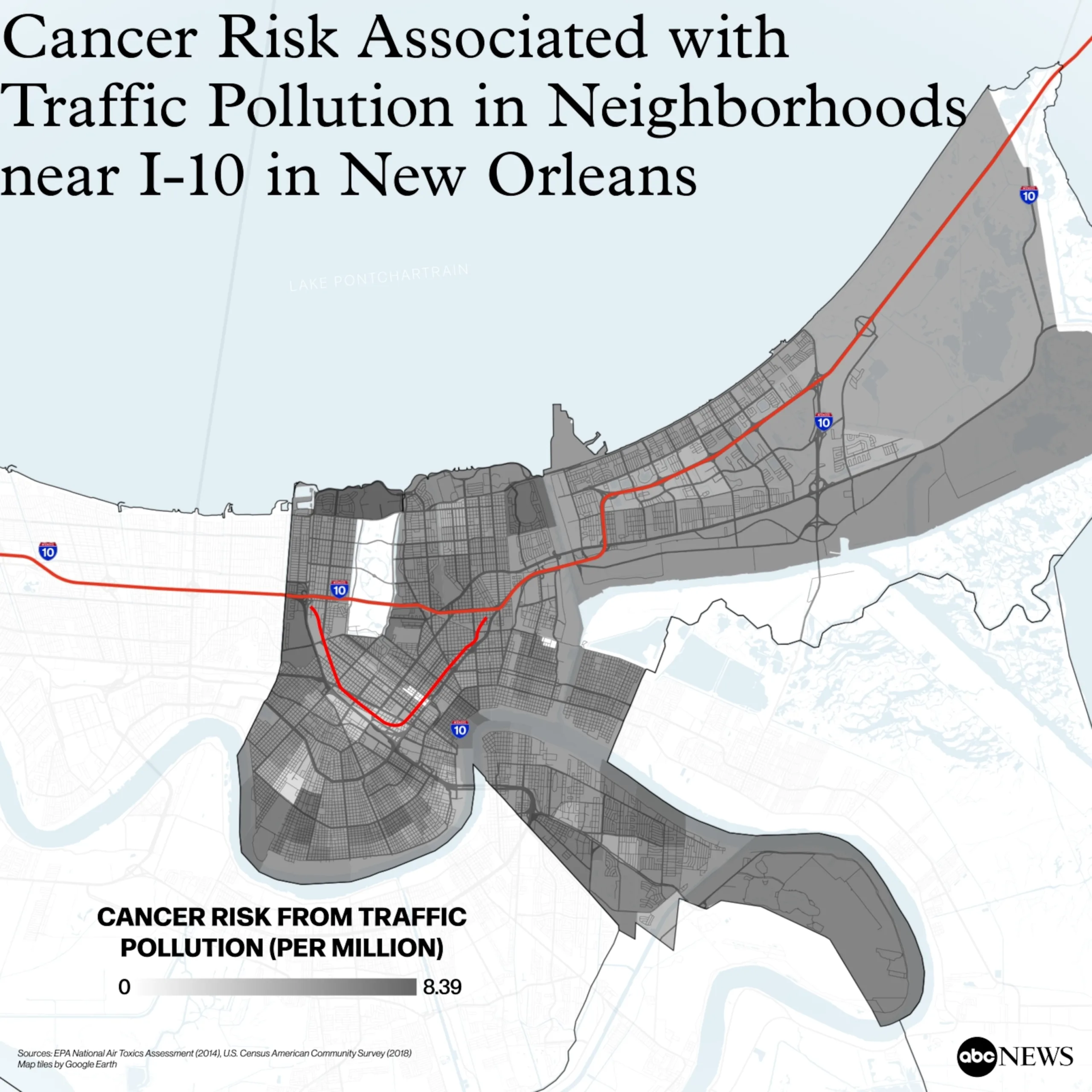

Along the I-10 Claiborne Corridor in New Orleans, residents in nine nearby neighborhoods have reason to worry.

In a 2019 Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center study, researchers found evidence that “air contaminants from continuous traffic” along the interstate create an environmental issue of “greatest potential concern” in the area.

Data from the ABC News analysis shows the 69 New Orleans tract neighborhoods within a mile of I-10 along the corridor have a cancer risk of 5.92 per million, a respiratory hazard index of .144, and an average asthma rate of 10.8% — all levels above national averages. The corridor area is about 81% nonwhite.

Cancer risk associated with traffic pollution in neighborhoods near I-10 in New Orleans

EPA NATA (2014), U.S. Census American Community Survey (2018)

Re-imagining the Claiborne Expressway

Over the past five years, the Claiborne Avenue Alliance—a coalition of residents, property owners and business leaders dedicated to the thoughtful development of the Claiborne Corridor — has led a renewed effort to advocate for the removal of the elevated expressway and rebuild the avenue below.

The group has already started documenting the negative effects the I-10 freeway has on adjacent neighborhoods, including the severe pollution from daily commuter traffic. In addition, the alliance has emphasized the positive potential outcomes of removing the freeway.

A restored Claiborne Avenue would attract new businesses and jobs to a once-vibrant commercial corridor, as many of the vacant lots adjacent to the highway become redeveloped, according to the group.

While admitting the expressway needs repairs and is a stain on the Tremé neighborhood, state highway officials and some local leaders note that removing it would mean rerouting more than 100,000 vehicles that use it every day, including commercial traffic connecting to the Port of New Orleans. That could hurt a major economy in the region, they say.

Advocates of the proposal to remove that portion of the highway, believe some of the estimated 50 acres of land reclaimed from removing I-10 could be used for affordable housing – addressing concerns from some residents that improvements could lead to gentrification and price them out of the neighborhood.

“You just can’t up and move that highway,” said Fred Joseph Johnson Jr., who lives in the Tremé neighborhood. “You have to make certain that there’s a safety net for the people that have fought, bled and died, and paid dues there. Other than that, they’re going to get taxed out. So, however much I don’t like it, I have to understand it’s kind of a quagmire. Certain things have to be done in certain order to make certain that folks don’t get displaced all over again.”

The I-10 removal efforts in New Orleans align with the vision of Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU), a Washington, D.C.-based group dedicated to steering cities and towns away from sprawling development and transit systems. CNU has the I-10 Claiborne Corridor on its 2021 list of “Freeways Without Futures” – 15 highways the group says “have left a terrible legacy and incredible hurdles for the people who live around them.”

CNU’s goal is to build support for a “Highways to Boulevards” movement in cities like New Orleans – to rethink the concept of urban freeways and replace aging, crumbling highways that have polluted neighborhoods with city streets, housing and green space.

Dr. Adrien Katner of Louisiana State University prepares local science students on a field trip to measure air pollution in a park beside the Claiborne Avenue Expressway.

Evan Simon/ABC News

By their count, freeways and highway thoroughfares that have pierced neighborhoods and aggravated pollution levels in at least 18 cities have been removed since the 1970s.

Critics of the “remove the highway” concept see it differently.

While repairing old freeways is costly, replacing them would cost billions, and perhaps worsen traffic congestion in other areas of town, they say. And while replacement may reduce pollution, some critics argue there’s no guarantee that removing a highway will spur new development in the neighborhoods around it.

Just like in New Orleans, reluctant residents in other cities believe newer housing and new businesses could “price them out” of their neighborhoods, forcing a new exodus from the nearby neighborhoods.

Moreover, any changes to a city’s landscape – like taking out a highway — would likely lead to new regional debates about who benefits from development. While rural and suburban commuters see interstates as a daily connection to work, urban entertainment and high-speed crosstown connectors, the freeways also are key to the nation’s economy.

A 2020 study published last year by the National Bureau of Economic Researchers found that if America were to remove its entire interstate highway system, the U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) would decrease by up to $578 billion (in 2012 dollars).

A buy-in from Congress

Nonetheless, some in Washington, D.C., have started to buy into the “Highways to Boulevards” movement.

The Reconnecting Communities Act, part of the $1 trillion infrastructure bill Congress approved in early November 2021, provides $1 billion for projects to restore neighborhoods torn apart by highways.

Proponents of the highway removal movement say $1 billion is a fraction of the $20 billion originally proposed for the program.

But they note it is the first time federal dollars have been put toward this type of restorative justice.

The Reconnecting Communities Program fact sheet notes the purpose of the program is “to reconnect communities by removing, retrofitting, or mitigating transportation facilities, like highways or rail lines that create barriers to community connectivity, mobility, access, or economic development.” The program funds both planning and capital construction proposals.

On February 28, 2023, U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg announced $185 million in grant awards for 45 projects through the new Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program – six construction projects and 39 planning projects.

“Transportation should connect, not divide, people and communities,” U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said during the grant awards announcement. “We are proud to announce the first grantees of our Reconnecting Communities Program, which will unite neighborhoods, ensure the future is better than the past, and provide Americans with better access to jobs, health care, groceries and other essentials.”

In New Orleans, Stelly’s not-for-profit agency, the Claiborne Avenue Alliance Design Studio, was one of the first to apply for a Reconnecting Communities grant. The agency, which specializes in community-based architectural and urban design, asked for $2 million to study the Claiborne Expressway and envision the neighborhood without it.

Amy Stelly and Nightline anchor Bryon Pitts walk beneath the Claiborne Avenue Expressway.

ABC News

At the same time, the Louisiana Department of Transportation submitted a $100 million proposal of its own that focused on beautification and maintenance of the highway instead of removal. The state’s proposal would keep the expressway largely intact, but better maintained, and build a public market and performance area underneath the highway to help the neighborhood economy.

The state received only a $500,000 “planning grant” toward its proposal. Stelly’s grant proposal through the Claiborne Alliance Design Studio was not funded.

While the future remains unclear about how “The Monster” in New Orleans will be dealt with, the planning grant will require the state to work with community leaders to develop a plan.

That gives many Tremé residents like Stelly continued to hope that the highway might be torn down and the neighborhood restored – culturally, environmentally and economically.

“I want the highway removed,” Stelly said. “Gone. There’s no in-between for me.”

Evan Simon, Investigative Producer, ABC News and Byron Pitts, ABC News Chief National Correspondent and Nightline Anchor, contributed to this report.