For what would have been Henrietta Lacks’ 103th birthday, her family got her some justice: A settlement with Thermo Fisher Scientific over the Massachusetts-based company’s use of cells obtained without her consent seven decades ago.

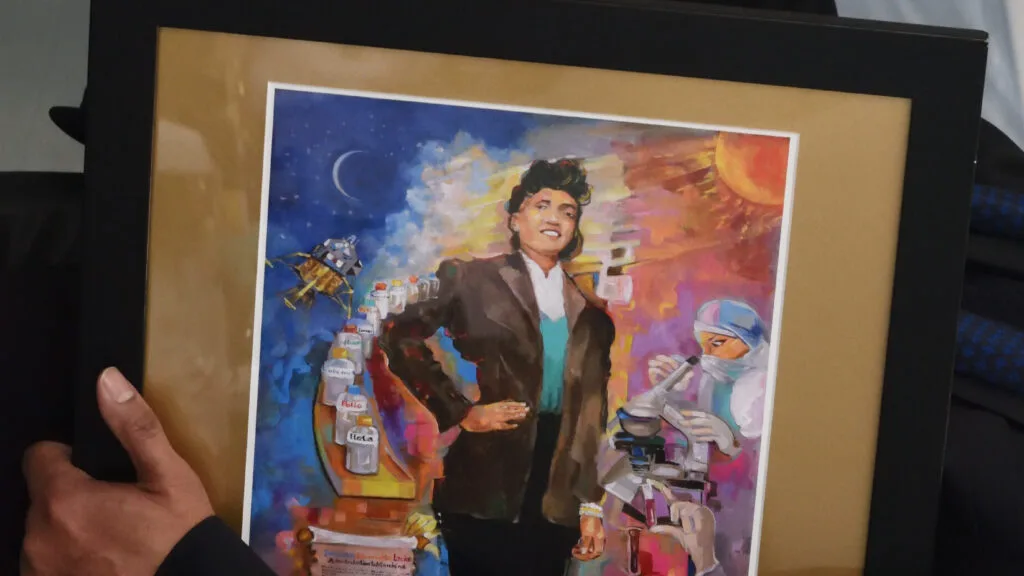

The story of Lacks, a Black woman whose cells have contributed to scientific breakthroughs ranging from the development of polio and cancer treatments to the mapping of the human genome, is one of the best-known tales of the exploitation of marginalized groups in the name of medical progress.

The terms of the agreement between Lacks’ family and Thermo Fisher — which initially tried to get the case dismissed, arguing that the statute of limitations had expired — are confidential. But experts in race and medicine say the settlement puts further pressure on the medical establishment to acknowledge and correct the harm that underlies much of the field’s historical practices.

“A lot of people don’t know how many groups of people were violently taken advantage of, were murdered, were experimented on, were tortured,” said Keisha Ray, assistant professor with the McGovern Center for Humanities & Ethics at UTHealth Houston. “They just don’t know that American health care and American medicine, [and the] American scientific community have these roots.”

Lacks’ place in medical history has drawn international attention since the publication of Rebecca Skloot’s 2010 best-selling book, “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.” In 1951, Lacks was admitted to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore with cervical cancer. A doctor at the hospital, George Gey, harvested Lacks’ tissue without her permission, which was legal at the time. Gey performed the first successful cloning of human cells and went on to use the cells — which he called HeLa cells, after Lacks — in medical research.

Lacks died later in 1951, at just 31 years old. But HeLa cells turned out to be immortal: While most cells die soon after being placed in a Petri dish, Lacks’ cells doubled about every 24 hours. They are still alive today, multiplying in labs all over the world, with an estimated 55 million or more used in at least 75,000 studies to date. They’ve saved countless lives and sparked the creation of the entire field of virology.

HeLa cells are also a big moneymaker. Johns Hopkins distributed them for free, but a number of biotech companies profit from products derived from the cells. Among them is Thermo Fisher, a biotech company with an annual revenue of over $40 billion. Lacks’ descendants sued Thermo Fisher in 2021 over its use of, and susbequent profiting from, HeLa cells in several of its products.

But until now, her family had not been compensated for their mother and grandmother’s contribution to medicine and science.

“What the settlement does is add a level of humanity that has historically been overlooked,” said Deleso Alford, a professor at the Southern University Law Center who wrote a landmark 2012 article about Lacks in the journal Annals of Health Law, and who filed an amicus brief in support of the Lacks family’s lawsuit.

Alford noted that “medical researchers and the scientific community purposefully hid Mrs. Lacks’ identity by referring to her own cells as ‘HeLa’ cells — using the first two letters of her first and last names.” The settlement, Alford said, “informs society that her unique cells cannot be disassociated from her being.”

Henrietta Lacks and the question of accountability

Thermo Fisher isn’t the only company that profited from HeLa cells, and it is unlikely to be the last to face a lawsuit, the lawyers representing Lacks’ family suggest. “The fight against those who profit and choose to profit off of the deeply unethical and unlawful history and origins of the HeLa cells will continue,” said Chris Ayers, one of the attorneys representing the family, at a Tuesday press conference in Baltimore.

Thermo Fisher and the Lacks family attorneys said in separate statements that “the parties are pleased that they were able to find a way to resolve this matter outside of court and will have no further comment.”

Biotech companies are also not the only ones responsible for the exploitation of Lacks’ cells, according to Ray, the author of “Black Health: The Social, Political, and Cultural Determinants of Black People’s Health.” Johns Hopkins is unlikely to be sued because the organization did not sell the cells, but that doesn’t necessarily absolve it from responsibility, she said.

While Johns Hopkins has acknowledged Lacks’ role in the advancement of science and has several programs to honor her, Ray said, “they don’t really admit any wrongdoing. They just sort of say, hey, this was legal. But legality is not the standard and can never be the standard for health care. It has to be ethical.” Johns Hopkins did not respond to a request for comment.

A step toward ‘recognizing and rectifying’ injustices

The Tuskegee study, in which the U.S. Public Health Service withheld syphilis treatment from Black men, is another egregious example of racial exploitation in the name of scientific progress, as are the brutal experiments conducted on enslaved Black women by James Marion Sims, known as the “father of gynecology.”

The Lacks settlement does not, strictly speaking, set a legal precedent for future family members and descendants of people who faced such abuses. But it matters greatly to the broader conversation on health equity, said Camara Jones, a commissioner at the O’Neill-Lancet Commission on Racism, Structural Discrimination, and Global Health and former president of the American Public Health Association.

“The settlement is part of recognizing and rectifying historical injustices, which is key to anything that we want to do,” Jones said.

Future lawsuits seeking compensation for unethical medical practices, particularly those based on racist discrimination, may look to this settlement as an indication that past wrongdoing can be rectified. “I think it is a signal that people need to become litigious,” Jones said. “I think that if you can get a lawyer, you can follow your claim.”

Yet addressing one case at a time does little to change the broader system, Jones added: “We need to go beyond individual restitution, to collective reparations.”