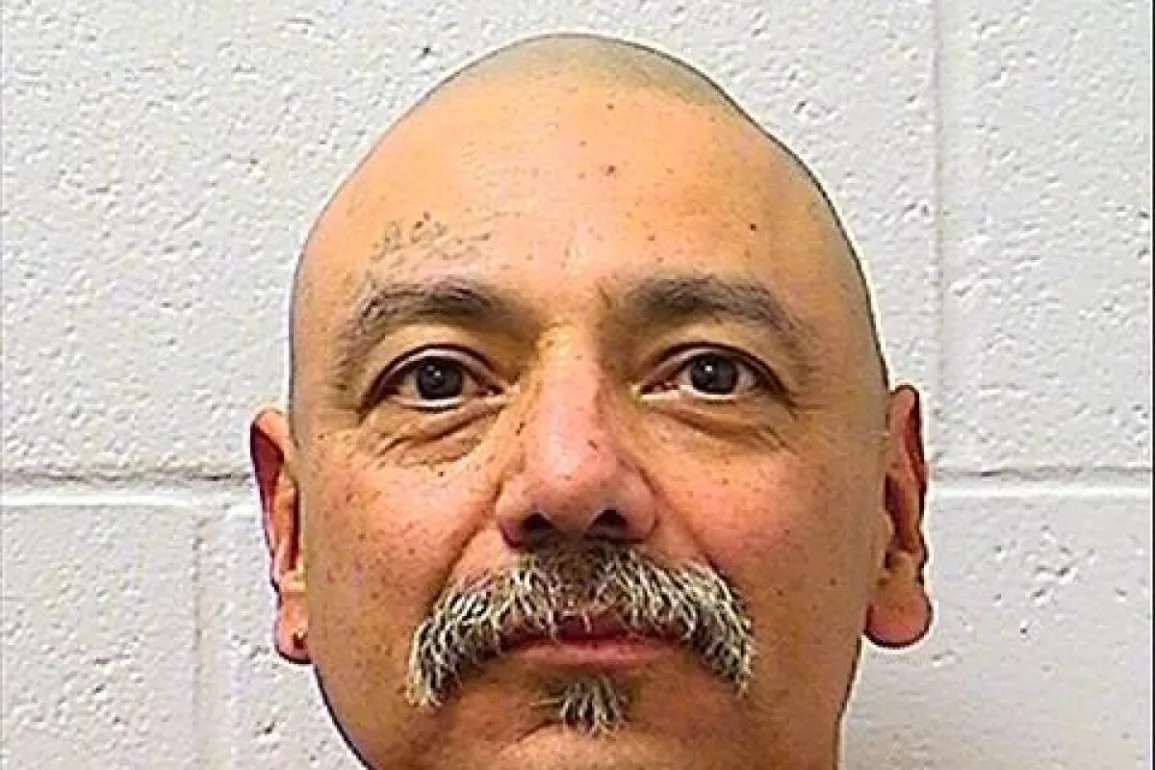

Michael Torres was an unlikely chief executive.

He had a fifth-grade education. On paper, at least, he was indigent. And he was serving a prison term of 133 years to life for attempted murder, conspiracy and witness tampering.

Yet Torres, 59, ran one of the most intricate and lucrative black market businesses in Los Angeles County: the jails.

His tenure running this illicit empire ended two weeks ago, when two inmates stabbed him to death on the yard of California State Prison, Sacramento. New players are already muscling in on the jails. And Torres’ killing may not have been the final one in the shakeup. A woman said to be associated with him was found shot to death in his mother’s home a week later.

The illegal economy of the Los Angeles County jail system moves along twin tracks: the trade of drugs and extorted commissary items inside the walls, and the exchange of money on the outside.

By driving out competitors and by the addictive nature of drugs, the Mexican Mafia can inflate the price of its most lucrative product without losing customers. A gram of heroin that costs $50 on the street sells for 20 times that in jail. The result is a circulation of a relatively small amount of drugs — a trade not of kilos but of “papers,” minuscule smears of heroin — that nets big profits.

The inverse is true for the trade of commissary goods — snacks, clothing, hygiene supplies — that the Mexican Mafia takes from inmates, which are resold at lower prices to undercut the jail-regulated market.

The conductor of this system was not even in the jails. Authorities have long said Torres ran them from his prison cell 400 miles away, using illegal cellphones and underlings eager to carry out his vision.

Torres did not create this economy, but interviews, testimony, records and wiretapped calls make clear that he refined it, ratcheting up the amounts of money that can be wrung from an imprisoned and largely poor customer base.

Along with his monthly collections from San Fernando Valley gangs, Torres invested the money in legitimate businesses, creating a web of influence and wealth that emanated from one man, making phone call after phone call from his prison cell.

Michael Torres, a member of the Mexican Mafia, was stabbed to death on July 6 at California State Prison, Sacramento.

(California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation)

The precise reasons for his fall from grace remain unclear, but investigators are probing his hold over the county jails, which had weakened in recent months, as a source of tension within the Mexican Mafia. Others in the organization, cut out of the jail rackets, had raised questions about where the money was going.

When Torres first took over the jails 20 years ago, an inmate predicted his ambition would one day get him killed. “They step on each other’s face to get to the top,” he told detectives.

Rise to power

Torres was born in 1964, the son of an immigrant who’d left his hometown of Jacona in the Mexican state of Michoacán at 17 to work in the fields outside Lompoc, according to his father’s obituary. Raised in San Fernando, a middle-class suburb built around an old Spanish mission, Torres fell in with the local gang, San Fer. He took on the name “Mosca,” Spanish for fly.

Torres said in court records he dropped out in the fifth grade, but a reading list later seized from his mother’s house showed his interests were eclectic: medicine, hypnosis, homemade explosives, the Freedom of Information Act, ancient Japanese war texts, and “The Gentle Art of Verbal Self-Defense.”

In 2003, Torres shot a man who had been extorting dealers and prostitutes in North Hills by claiming to be a member of the Mexican Mafia. Booked into Men’s Central Jail for attempted murder, Torres shared control over the county jail system with another Mexican Mafia member, Armando “Perico” Ochoa, a high-ranking member of the MS-13 gang told the authorities.

Torres took sole control over the jails after Ochoa was sent to prison, the MS-13 member, Nelson Comandari, told the FBI. Comandari claimed that when a MS-13 member who’d worked for Ochoa refused to step down, Torres put a “green light” on MS-13, meaning all Latino inmates were obligated to attack any member of the gang on sight. With MS-13 inmates being stabbed twice a day, Comandari said, he scrounged together $2,300 from his gang and paid Torres to lift the green light.

Torres saw the jails were a place where people who owed money or cooperated with the police would eventually end up. Behind bars, debts could be collected, discipline meted out, perjury suborned. Torres would be convicted of threatening two witnesses, both inmates, in his attempted murder case.

One would-be witness told detectives a woman approached him in the jail’s visiting room and held up a note. If the inmate talked to the police, it read, “I’ll kill you and your family just to let you know not to f— with the Eme.” Then she swallowed the piece of paper.

Another witness said a woman showed him a note instructing him to blame someone else for the shooting with which Torres was charged. She showed him the back of the note, where his mother and girlfriend’s phone numbers were written. “That was a threat,” he told detectives.

“We’re just pawns in their chess game,” he said. “No matter what happens to us, it doesn’t matter.”

Convicted of attempted murder, witness tampering and conspiracy, Torres was sent to prison for life in 2007. The jails were passed onto Eulalio “Lalo” Martinez, who died of an overdose in 2013, and then to Jose “Fox” Landa-Rodriguez, according to testimony at the trial of Gabriel Zendejas Chavez, a lawyer accused of helping Landa-Rodriguez run the jails.

Newsletter

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you’re an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Witnesses testified at Chavez’s trial that Landa-Rodriguez controlled Men’s Central Jail and Twin Towers in downtown Los Angeles but ceded the jail complex in Castaic, known as Wayside, to Robert Ruiz, a Mexican Mafia member who was living in Tijuana.

After Landa-Rodriguez lost control of the downtown facilities in early 2016, Torres stepped in as a caretaker, law enforcement officials and gang members said. He used cellphones to manage the jails from his prison cell near Sacramento, according to testimony and recorded calls. Records filed in federal court showed that from 2016 to 2019, he was caught with a cellphone nine times.

Ruiz, whose nicknames were “Peanut Butter” and “Chino,” died from natural causes six months after Torres’ takeover. That day, Daniel “Danny Boy” Piña called another Mexican Mafia member, Jose “Joker” Gonzales.

“Half of it was going to Peanut Butter,” Gonzales said in the wiretapped call, referring to the jails. “Is that what you’re saying, that that goes to Mosca now?”

“Yeah,” Piña said. “Well, they wanted — they, they had a meeting and they said, ‘Look, whatever Chino had, that that was going to be put in the pot for like they’re doing in the county.”

Big business behind bars

The Mexican Mafia has two main schemes in the jails: the “kitty” and a drug tax.

The kitty is a pot of snacks, clothing, and hygiene items collected from Latino inmates, who must contribute whenever they make a purchase at the commissary. A jailhouse note that laid out rules for new inmates stated, “Donations are $1.50 for every $10.”

The kitty is then sold within the jail, creating a secondary, cheaper market for commissary goods. The items sell quickly because they are undervalued, an FBI agent testified at a recent trial. The Mexican Mafia member controlling the kitty doesn’t care because it is all profit.

The other racket is a tax on drug sales, chiefly heroin. Heroin most often enters the jails hidden inside the human body. A dealer will secret the drug in his rectum or swallow a balloon full of it, then turn himself in for an outstanding warrant or get arrested on a minor charge.

The margins are huge. Before Torres took over, a gram that cost $50 on the street could be sold for $700 in jail, according to testimony.

Torres raised the price of a gram to $1,000, according to gang members who worked for him. His customer base could not go elsewhere: Latinos, who make up about 55% of the county jail population, are not allowed to buy from dealers of other races. Anyone who violates the rule is beaten in 13 second intervals.

According to an indictment brought in federal court, Torres’ predecessor, Landa-Rodriguez, allowed anyone to smuggle drugs into the jails so long as they gave him one-third of their product, which his subordinates then sold. Landa-Rodriguez has pleaded not guilty and has yet to go to trial.

But Torres realized he could make more money by reducing supply, said a law enforcement official who was not authorized to speak publicly. Only his underlings could bring in drugs, which were then sold at inflated prices, the official said.

A view of Men’s Central Jail

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

At the retail level, heroin is divided into tiny smears called “papers” and sold for $50 to $100. Unable to possess cash, inmates instruct a relative or associate outside of jail to purchase a Green Dot or similar prepaid debit card. The number on the back of the card is sent to a person on the street, who cashes out the balance and tells a dealer inside the jail to give the customer his product.

It is difficult to gauge how much money the jails generated, but authorities estimated in a recent trial that Torres’ lieutenant was collecting about $12,000 a week from drug sales and the kitty in 2017.

A gang member familiar with his operation said Torres used some of the money to open businesses in the San Fernando Valley, including a hair salon, a tow truck company, a tattoo parlor, and a flower shop. Public records and a LinkedIn page show his relatives owned a flower business and managed a beauty salon.

For his part, Torres claimed in divorce paperwork that he had no assets whatsoever.

Torres won favor with other Mexican Mafia members by allowing them to send drugs into the jails on a rotating basis, cashing them out with payments of $15,000 to $20,000, according to gang members familiar with the jail drug trade.

He also settled their scores. An underling was recorded telling an inmate to give a “birthday hug” to another prisoner whose sister had insulted a Mexican Mafia member. “Let him know that this homie Psycho from Santa Monica said to tell his sister to not put his name in her mouth anymore and she better leave the city,” he said on a recorded jail phone.

Twenty minutes after the call, deputies found the inmate covered in blood, his nose broken and his right eye swollen.

By sharing the money and doing favors, Torres’ standing in the Mexican Mafia grew. But wiretapped calls suggest others in the organization were glad to have him as a lightning rod to draw the attention of law enforcement and front the internal strife that came with running the jails.

“It’s a good spot, homes,” Piña told Gonzales, “but you got to deal with — you got to put out a lot of fires, homes, you know? Constant drain on attention.”

Piña proposed that he and Gonzales “put some stuff in there” and “deal with individual people,” but he didn’t want his name on the marquee. “Whose ever name’s out there,” he warned, “is going to be top f—ing in the middle of all them damn people investigating that.”

Torres, he said, was “willing to deal with all the headaches and the heat.”

‘Something that will be addressed’

In 2017, Robert “Dopey” Hinojos was booked into the county jail for murder. A member of a Paramount gang called Brown Nation, Hinojos had been sponsored for membership in the Mexican Mafia by Torres, according to testimony at his trial last year.

After his arrest, Torres held a conference call with leaders of four Paramount gangs and told them to raise money for Hinojos’ legal bills. “I already put a payment down of 11 grand,” Torres said in the recorded call.

Because Hinojos was being held in solitary confinement, Torres said he and another Mexican Mafia member would collect the monthly tax from Paramount’s gangs. “Once he has — he has access, then we’ll get everybody on the line and officially hand it over to him,” Torres said. “Until then everything remains the same.”

This arrangement would open a rift between Hinojos and his sponsor. Not only was Hinojos cut out of his hometown’s rackets, he was sidelined in the jails as well.

By tradition, a Mexican Mafia member has the right to run the facility where he is being held. But when Hinojos got to Men’s Central Jail, Torres declared that “everything stood the same,” a witness told detectives. “Everything would continue to work the same way it was. Just because any brother shows up doesn’t necessarily gonna give him the — the rights to go ahead and take over.”

After five years in what he called “the dungeon,” Hinojos was released from solitary in 2022. He called an associate and launched into a 20-minute rant, recalling the time he told his girlfriend he was not being “taken care of.”

“She’s like, ‘Well, maybe they don’t take care of you because you don’t ask.’ And I said, ‘I shouldn’t have to ask for what’s mine.’ I said, ‘What’s mine should just be given over.’”

Hinojos hinted the money from the jails was not being shared. “I don’t know where all those funds are, homie,” he said. “I really don’t.”

Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Pitchess Detention Center.

(Los Angeles Times)

“There’s a lot of people stealing. There’s a lot of people doing foul s—,” Hinojos said, adding, “I’m like, ‘Do you guys understand that this is going to come out?’”

“Whether it’s me going back out to the streets or if I get f—ing benched out and have to do life upstate,” he said, “it’s something that will be addressed.”

Convicted of murder and sentenced to life without parole, Hinojos was sent to state prison in June.

By then, another Mexican Mafia member was muscling in on the jails from state prison, according to law enforcement officials. The sources said Torres had lost Men’s Central Jail and Twin Towers but was still holding onto the Wayside complex when, on July 6, he was stabbed to death.

Authorities identified his assailants as Ray Martinez, 49, and Juan Angel Martinez, 47. Ray Martinez is a Mexican Mafia member from MS-13 called “Cisco,” law enforcement sources said. He and Juan Martinez, who are not related, were already serving life in prison for murder.

Eight days after Torres was killed, San Fernando police were called to a home on Kewen Street that belonged to Torres’ mother.

Detectives had searched the house 20 years earlier, finding bundles of cash in the crawl space and letters Torres had mailed home from prison.

On July 14, police found Stephanie Rodriguez, 38, dead from a gunshot wound. Rodriguez was said by a law enforcement official to have been acting as Torres’ “secretary,” collecting his money and relaying his orders. She sometimes held herself out as his wife, but Rodriguez was not legally married to Torres, the source said.

Lt. Daniel Vizcarra of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, whose detectives are investigating the case, said he could not confirm a connection between Torres and Rodriguez.

In a strange turn, Torres’ niece, Evelyn Torres, 34, was arrested at the scene on suspicion of Rodriguez’s murder. Both Rodriguez and Evelyn Torres lived in the home where Rodriguez was killed, Vizcarra said. Asked whether a dispute precipitated the shooting, he said: “That is unknown at this time. That would be hearsay.”

It’s unknown if Rodriguez’s death was collateral to Torres’ killing, or if the timing was simply a coincidence. But Torres, who had a history of using women to manage his affairs, understood the risk of bringing her into his world.

In 2016, Torres held a conference call with five other Mexican Mafia members. “Look, OK, hey,” one of the men said. “Your ruca, your hyna” — slang for woman — “whatever, gets involved, starts acting like, like she’s a carnal, she’s getting in our business? Hey, we treat her the same.”