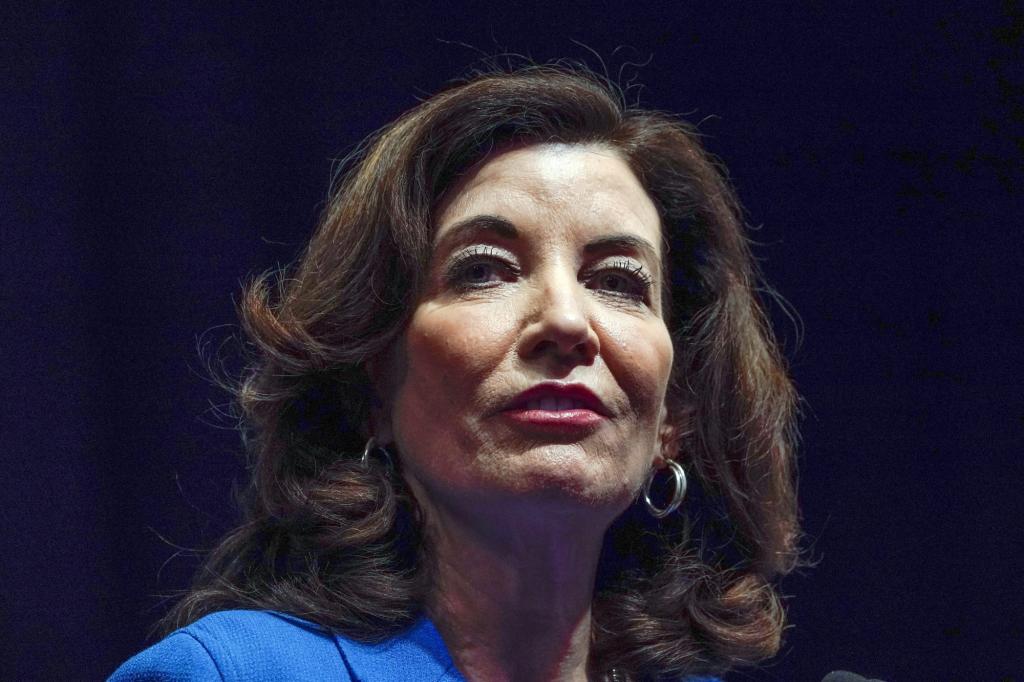

Before ending its session this year, the state Legislature passed the Jury of Our Peers Act; it’s critical that Gov. Hochul veto it.

The bill would repeal New York’s ban on felons serving on juries — going far beyond the current administrative process that allows New Yorkers with a single felony conviction to get their jury-service-eligibility restored.

The bill’s sponsors, state Sen. Cordell Cleare and Assemblyman Jeffrion Aubry, insist this would benefit black New Yorkers by shifting the racial composition of juries.

But in reality, the bill’s most consequential result would be to tilt the scales of justice yet further toward criminals.

Potential jurors who are convicted felons would still be unlikely to serve; instead, prosecutors would be forced to use some of their limited number of peremptory challenges during jury selection to reject them.

After all, would an assistant district attorney allow a gang member with multiple convictions to adjudicate a gang assault?

Restoring felons’ jury-service rights would thus create another advantage for defense attorneys, whose own peremptory challenges would remain undiminished.

Further, equating convicted felons with black citizens is misguided and, bluntly, racist.

Advocating in Albany, New York Civil Liberties Union executive Perry Grossman claimed, “For decades . . . our state’s jury ban has shut thousands of black New Yorkers out of civic engagement, denying people of color the ability to fully participate in our state’s democratic process.”

But elevating black felons isn’t a boon to the communities they prey upon.

Indeed, violent crime in New York City is predominantly intra-racial: Last year, 57.1% of murder victims and 57.0% of murder suspects were black.

Similarly, 65.6% of shooting victims were black, as were 65.6% of shooting suspects.

The bill’s sponsors argue that the jury service ban “helps perpetuate the cycle of mass incarceration that ensnares thousands every year,” and that “our criminal system is stacked against . . . low-income Black people.”

But why would a jury of exclusively law-abiding citizens be more likely to penalize innocent black defendants?

Anyone called for jury duty can attest to its melting-pot mix of a city’s racial and socioeconomic pool.

By insisting that the status quo “robs all of us of our right to a jury of our peers,” Aubry and Cleare are implying that felons are definitionally blacks’ peers.

Indeed, our system is stacked against victims.

Guilty pleas have fallen statewide from half of all disposed cases in 2019 to just over a third last year.

Even the number of trial verdicts fell from 2,663 in 2019 to just 1,737 in the same period of 2023.

In the city’s criminal court, guilty pleas have dropped further — to under a quarter of prosecuted cases as of 2022.

Meantime, dismissals have ballooned from 45% of cases in 2019 to a full two-thirds last year.

Crime victims — in the Big Apple, they’re disproportionately black — stand increasingly less chance of receiving justice.

With each “reform,” the deck is stacked higher against prosecutors.

Discovery reform in 2020, in particular, created an impossible compliance burden, requiring assistant district attorneys to triage their caseloads, dismissing hundreds of thousands of viable cases.

Of course, the loudest advocates of this bill are those whom it truly helps: felons too lazy to apply for jury rights through existing mechanisms or who have committed too many crimes to be eligible, and the attorneys who represent them.

One leading proponent is Neighborhood Defender Services of Harlem staff attorney Daudi Justin, who argued in US District Court this year that the jury-service ban is unconstitutional.

Per court documents, Justin, after his felony drug conviction, “chose not to avail himself of New York’s process for restoring jury service eligibility ‘after learning how burdensome and intrusive the process is.’”

Justin’s advocacy highlights how much easier his job would be if more potential jurors were past clients.

“The juries I see as a public defender in Manhattan do not share life experiences with people who have been charged with crimes,” he explained, “and this means that people I represent are not afforded a jury of our peers.”

It’s crucial that Gov. Hochul veto this bill, affirming that such patronizing racism has nothing to do with fairness.

True fairness is when crime victims — of any race — stand a fighting chance in court.

Hannah E. Meyers is a fellow and the director of policing and public safety at the Manhattan Institute. From City Journal.