On the campaign trail in 2021, a majority of candidates for city offices supported shuttering the Boston Police Department’s controversial gang database and ending the department’s cooperation with federal immigration authorities.

Among those in opposition was Michelle Wu, who ran for mayor on a progressive platform. Now Wu finds herself standing in opposition to an array of civil rights groups, councilors of color and criminal justice reform advocates as she seeks approval from the city council for a three-year, $3.5 million grant that would enable the Boston Regional Intelligence Center (BRIC) to hire additional staff.

The Center maintains BPD’s controversial gang database and shares information with immigration agents.

“Expanding BRIC with these grants will expand its harms, which have predominantly impacted Black, Muslim and immigrant communities, as well as activists across the region,” said Fatema Ahmad, executive director of the Muslim Justice League, who testified during a City Council hearing Sept. 29.

Wu, questioned about her flip-flop on BRIC last week, told WBUR the agency has improved since she became mayor two years ago.

“There’s new leadership of the police department, new structures in place as well,” she said. “The city of Boston has since created and stood up OPAT, [the] Office of Police Accountability and Transparency. There’s also been the POST [Peace Officer Standards and Training] commission at the state, another mechanism for accountability of law enforcement statewide.”

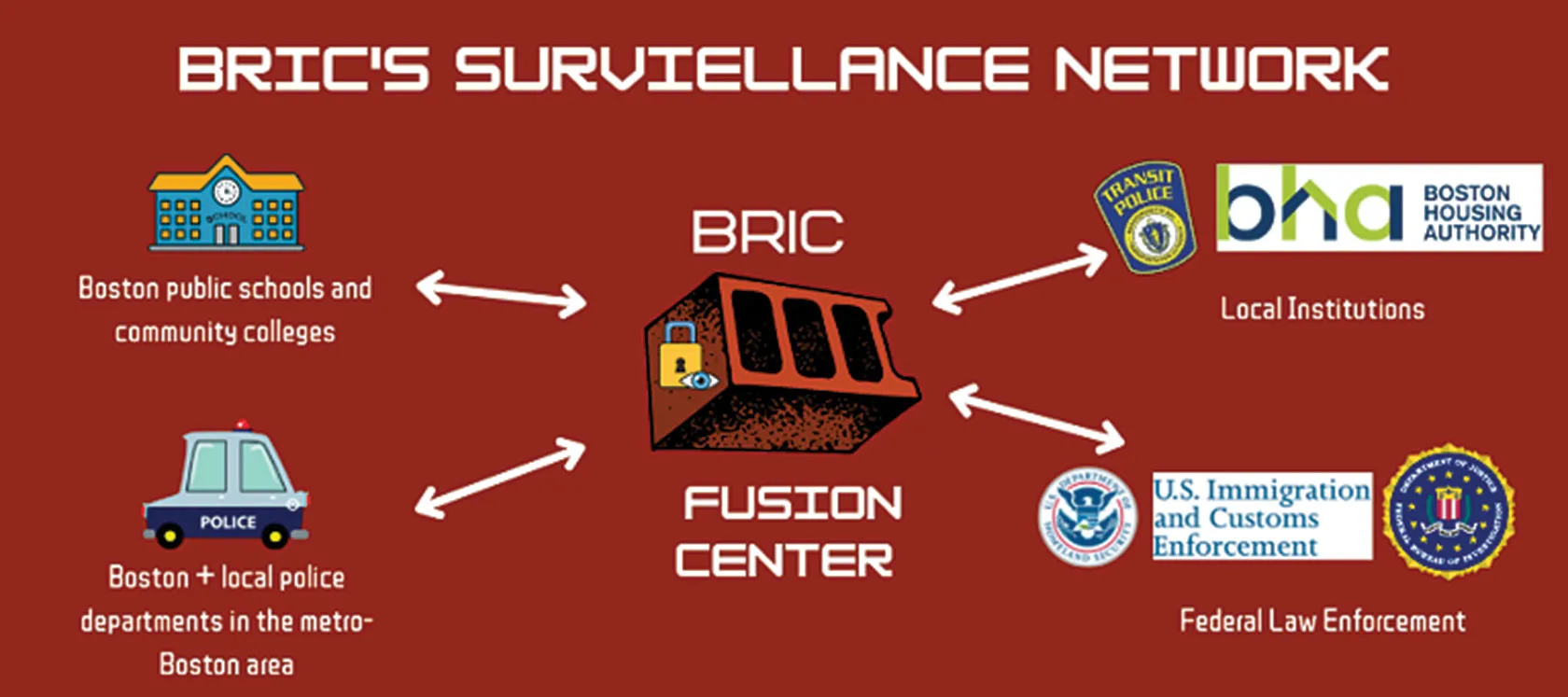

BRIC is a so-called fusion center, one of 79 recognized by the Department of Homeland Security, designed to facilitate information-sharing between local and federal law enforcement, intelligence and immigration agencies.

BRIC’s coverage area includes Boston and eight surrounding cities and towns. Critics of the fusion centers, which were originally intended to help federal authorities detect and track terrorist threats, say law enforcement agencies such as the Boston police have used them to track nonviolent social justice activists, including the Black Lives Matter movement, while ignoring threats from neo-Nazis and other white extremists.

While Boston police officers have tracked activists with Occupy Wall Street and other left-leaning groups, a white nationalist Proud Boys march in downtown Boston in July of last year appeared to catch Boston police flat-footed as dozens made their way through the city, at one point assaulting activist Charles Murrell. A year later, no one has been charged in connection with Murrell’s assault.

Police officials and civilians working with BRIC are responsible for maintaining the BPD’s gang database, where officers compile information on individuals that police determine to be gang members. The department’s cooperation with federal authorities drew attention in 2018 when agents from the federal Department of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) arrested an East Boston teenager BPD officials had identified as a gang member and began deportation proceedings.

In a 2022 ruling on the teen’s pending deportation, a panel of judges in the U.S. First Circuit Court of Appeals found that BPD’s system of determining whether people are gang members or gang affiliated was based on “an erratic point system built on unsubstantiated inferences.”

In May this year, Massachusetts Attorney General Andrea Campbell announced an investigation into allegations of bias in the BPD Youth Violence Strike Force, commonly known as the gang unit. African Americans, who make up 22% of the city’s population, account for 66% of those in the gang database. Whites, who make up 45% of the city’s population, account for 2.3% of those in the database, according to a WBUR analysis of data that the department released in 2019.

Ahmad said the 2018 case was just a part of the problem with the department’s gang database and its information-sharing with federal authorities.

“There are countless others impacted by BRIC who will not be able to testify to the Council — and many who may not know that BRIC played a role in their harassment, incarceration or deportation,” she testified at the Council hearing. “Expanding the Real Time Crime Center or any other parts of BRIC with these grants is a massive step in the wrong direction and would undo some of the progress made in 2020 by this Council in response to thousands of community members’ demands.”

Also testifying, Jillie Santos, community engagement coordinator for Citizens for Juvenile Justice, noted that Lawyers for Civil Rights found more than 140 incidents of BRIC sharing information about BPS students with ICE.

“A label of gang affiliation is a kiss of death in immigration court,” Santos said.

While BRIC and the gang database are unpopular with criminal justice reform advocates, several councilors appeared supportive. At-large Councilor Michael Flaherty, at an earlier Council meeting, moved to approve the $3.5 million in grants to BRIC without a hearing, but was countered by his colleagues, losing on a five-to-seven vote. Friday, Flaherty reiterated his support for BRIC.

“Public safety is paramount for our city,” he said. “It’s what separates us from other cities across the country.”

Boston City Council President Ed Flynn, too, said the agency is critical to keeping Boston safe.

“Boston [is] an international city,” he said. “Providing these grants — this money — will ensure that Boston police are able to continue their important mission.”

Others, including at-large Councilor Julia Mejia, noted that crime in Boston has been in a years-long decline.

“Because crime is down, why the urgency to secure this funding?” she asked Boston Police Superintendent Michael Cox.

Cox acknowledged that crime statistics have declined in Boston, but said increased funding and personnel at BRIC would be necessary to help the department respond to evolving threats.

“Crime and criminals — they develop, they grow, they change,” he said. “We’re just trying to keep up.”

During public testimony, Alex Marthews, national chair of the police reform group Restore the Fourth, complained about BRIC growing beyond its original anti-terrorism mandate.

“There’s not enough — in terms of threatening groups, in terms of terrorist groups — to sustain an office of 50 people,” he said. “What we’re seeing is a lot of ‘mission creep’ — surveillance of protestors, data-fueled harassment of young people of color, and a lot of what you might kindly call bureaucratic entrepreneurship, to extend the mission.”

The Council is scheduled to vote on the $3.5 million in grants to BRIC at its Oct. 4 meeting.