The law also distributed $1 million between three state agencies to commission memorials that mark the harm caused by forced or involuntary sterilizations. The process required consultation with survivors and advocates. However, a review of the state’s memorialization efforts by UC Berkeley’s Investigative Reporting Program and KQED revealed that after making minimal progress in its first year the state rewrote its contracts to eliminate community engagement requirements that it had apparently failed to meet.

This story’s reporting is based on multiple public records requests, more than 600 pages of documents, and interviews with lawmakers, public officials and prison representatives. In interviews, advocates and survivors told KQED they feel excluded and disrespected.

“[The memorialization process] echoes what we saw across the whole program, which was a following of the letter of the law and not the spirit of the law,” said Jennifer James, an associate professor of sociology at UCSF and member of CCWP.

‘Revictimized and silenced again’

The memorial funding went to the three state agencies that allowed the forced sterilizations to occur: the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, the California Department of State Hospitals and the California Department of Developmental Services. The agencies were charged with leading a collaborative memorialization process that would “acknowledge the wrongful sterilization of thousands of vulnerable people,” according to the legislation.

In their 2022 contracts with the California Victim Compensation Board, which oversees the reparations program, the state agencies were required to hold regular meetings, submit quarterly progress reports and create project teams that included survivors and advocates. Roughly one year later, the agencies had not fulfilled any of those requirements.

Instead of being held accountable by the compensation board, the agency’s contracts with the compensation board were rewritten.

The revised contracts reduced opportunities for community participation and transparency, according to KQED’s analysis of the original and revised contracts. For example, the requirement for agencies, survivors and advocates to meet “weekly or monthly to discuss and finalize the design, location and language that will appear on the markers or plaques” was deleted, as was the stipulation for agencies to provide quarterly reports.

When asked about the changes to the memorialization contracts, the compensation board said in a statement that “the contracts were amended to better reflect the roles and responsibilities of each department as described in state law. CalVCB’s statutory role is strictly fiduciary.”

Additionally, the funds originally earmarked for memorials have been almost cut in half to $550,000. It’s unclear how any unspent money will be used.

The state allocated $7.5 million to the two-year program, with $4.5 million earmarked for compensation, $1 million for memorialization and $2 million for program administration and outreach. Each individual whose application is approved receives $15,000. A second and final payment of $20,000, signed into law by Gov. Gavin Newsom in September 2023, will be processed by October. Up to $1 million of any remaining compensation funds could be extended for survivors if legislation is passed in the next few years.

When reparations advocates passed the legislation, they envisioned a collaborative and reparative process with the state where survivors, activists and community members could shape a memorial using the artists and materials they selected. Now advocates and survivors like Kelli Dillon, an advisor of the reparations bill, say they feel cheated.

“We thought we were going to be in partnership [with these agencies], and we were totally revictimized and silenced again,” said Dillon, who was coercively sterilized in 2001 at Central California Women’s Facility and was approved for reparations.

Records show that CDCR contracted Boules Consulting in July 2022 at $100 an hour to facilitate 30 hours of meetings between the agencies and the community, but only one meeting was held. Three days before it took place, the compensation board invited the eight survivors whose applications had been approved.

The meeting was a critical turning point. There was a tense back and forth between agency representatives and advocates, who shut down the meeting because only two survivors could attend on such short notice. A survivor-centered memorialization process, advocates argued, was contingent on meaningful outreach, opportunities for participation, inclusivity and accessibility.

Agency representatives postponed the meeting so more survivors could attend. Instead, according to records obtained through a public records request, CDCR’s Chief of Legislative Affairs, Sydney Tanimoto, emailed Boules Consulting to say there had been a “change of plans.” CDCR would move to a survey format instead of virtual meetings.

“The Administration pivoted to a survey model to address accessibility concerns raised by stakeholders as part of the initial stakeholder meeting,” Terri Hardy, a CDCR press secretary, said in a statement to KQED.

Survivors and advocates were deeply troubled by the decision.

“It could have been a historic moment where people who were greatly harmed could have gained a form of reparation through the process and that was lost,” said Cynthia Chandler, an attorney in Alameda County District Attorney Pamela Price’s office who helped draft the reparations law. “That can’t possibly happen through a survey.”

A short questionnaire was sent to a dozen advocates and survivors to assess their visual, auditory and language needs to participate in the survey process. Advocates with expertise in disability rights who had attended the meeting were not consulted, according to Silvia Yee, public policy director at Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund.

The first survey related to the design, location and language of the memorials was sent to 24 survivors whose applications had been approved. Based on six responses, the consultant wrote a final recommendation report suggesting the memorial be placed in front of the state capital and CDCR headquarters. A second survey, related to the language for the memorials was sent nearly five months later to 94 survivors. About a third responded.

Now, agencies say that they plan to install plaques, benches and gazebos at nine facilities where the sterilizations took place. As of March 26, the agencies had spent roughly $170,000. By the end of its contract, Boules Consulting had charged CDCR $9,900 for the work.

In response to KQED’s findings, the four state agencies sent a joint statement, saying that they “have worked together in partnership to meet and surpass the requirements established in the legislation.”

“All four departments recognized stakeholder input was a critical part of the process,” the statement continued. “Each department worked with CalVCB to actively engage in outreach efforts by using information collected and conducting targeted searches in hopes of reaching more survivors.”

Pulido said she never received a survey.

“It feels cold,” she said. “We should have been asked what kind of memorial we wanted.”

She said that if she had been asked, she would have replied that she’d like the memorial plaque to carry her name.

“I want them to know that I was victimized,” she said. “Remember me. Remember my fight and what I went through.”

Survivors of prison sterilization aren’t the only ones frustrated by the state’s memorialization efforts. Between 1909 and 1979, at least 20,000 Californians — disproportionately women and racial minorities — were forcibly sterilized while at state-run homes and hospitals.

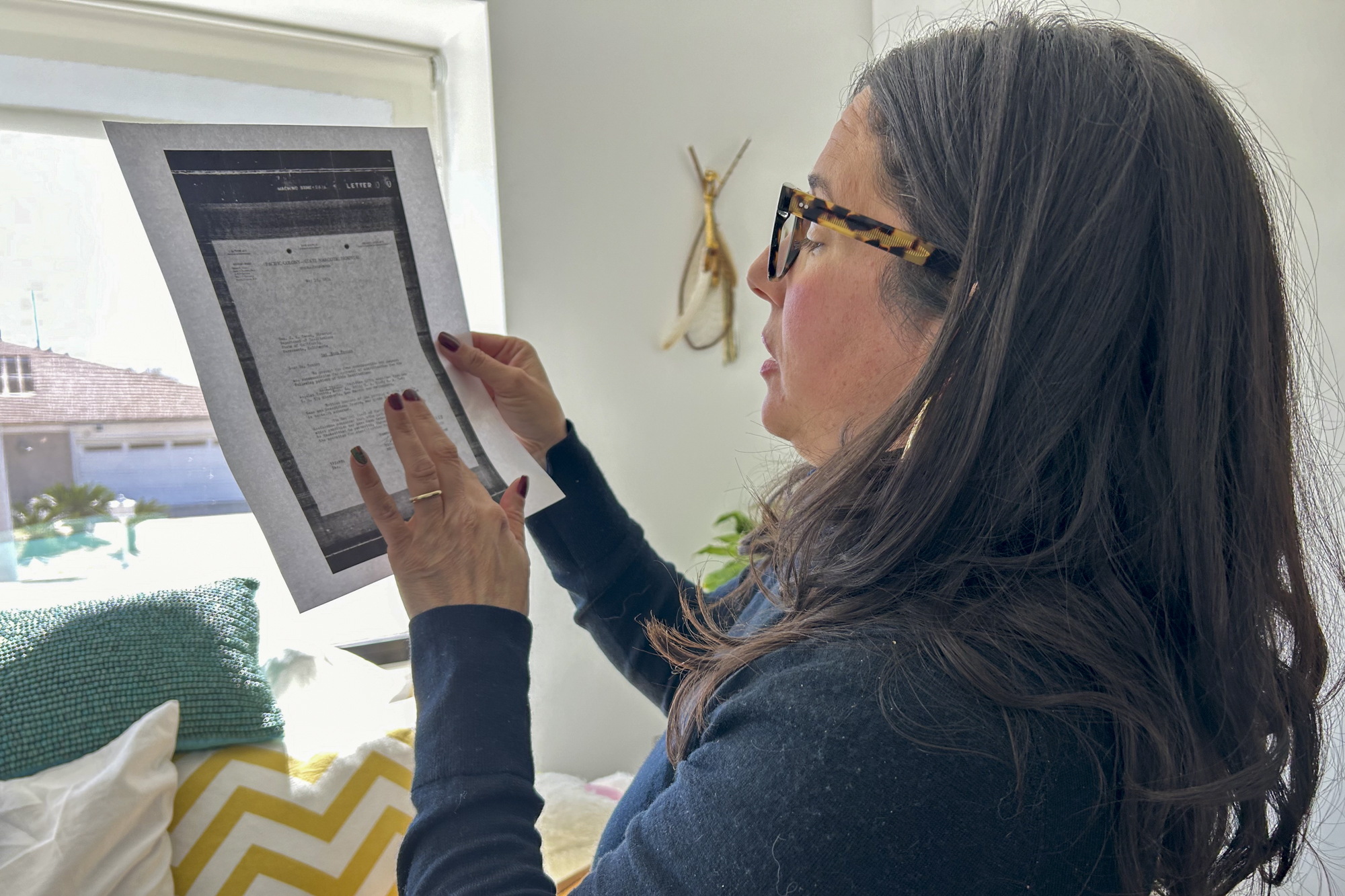

The state’s memorialization plans don’t include any markers at Pacific Colony, a former state hospital. This upsets Stacy Cordova, whose great-aunt, Mary Franco, was sterilized when she was 13 at Pacific Colony in 1934. Franco had been institutionalized after being molested by a neighbor. She was labeled a “sex delinquent” and “low moron,” according to facility records reviewed by KQED.

Cordova said she never received a survey. “Why have I never been contacted?” she said. “It really makes me sad that this promise has gone unfulfilled.”

Cordova, a special education teacher who lives in Azusa, made her own memorial. She created a historical radio project titled “American History EugeniX” to be used as a curriculum in high school and college classes. She will share the histories of people who were sterilized in the 1920s and 1930s based on eugenics records she found in the California State Archives. She hopes to launch the project this month.

‘You have to gather stories’

After the reparations law was passed, advocates and researchers tried to guard against the exclusion many now feel. They prepared a guidance document for the state agencies to follow as memorials were created, noting that including community input, specifically from survivors and their descendants, was crucial to the process.

An omission of survivor input, the document stated, “conveys not only an ugly message about state power, but ultimately will constitute a failure of contemporary agencies to properly acknowledge their role in past wrongs and harms.”

The document provided examples of memorialization projects from around the world, which are seen as successful because survivors were “active partners in the conceptualization and placement.” Advocates pointed to Los Angeles General Medical Center’s “Sobrevivir,” which recognizes hundreds of survivors who were forcibly sterilized at the hospital during the 1960s and 1970s.

Artist Phung Huynh made “Sobrevivir,” a monument with roses and praying hands etched into steel, with a budget of roughly $100,000. The flat disk is in the medical center’s courtyard. Huynh said she spent a year gathering input on what her piece should look like through open forums and correspondence with descendants of survivors and activists.

“You have to gather stories, be sensitive and thoughtful because it’s going to live in the community that it’s serving,” Huynh said of public art. “They have to feel like it represents who they are and the specific history that we’re trying to remember.”