Kansas, like many states, has heard considerable hullabaloo about banning books from libraries and schools. Taking the heat are books about LGBTQ+ people and U.S. history from the perspective of Americans of color, especially Black Americans.

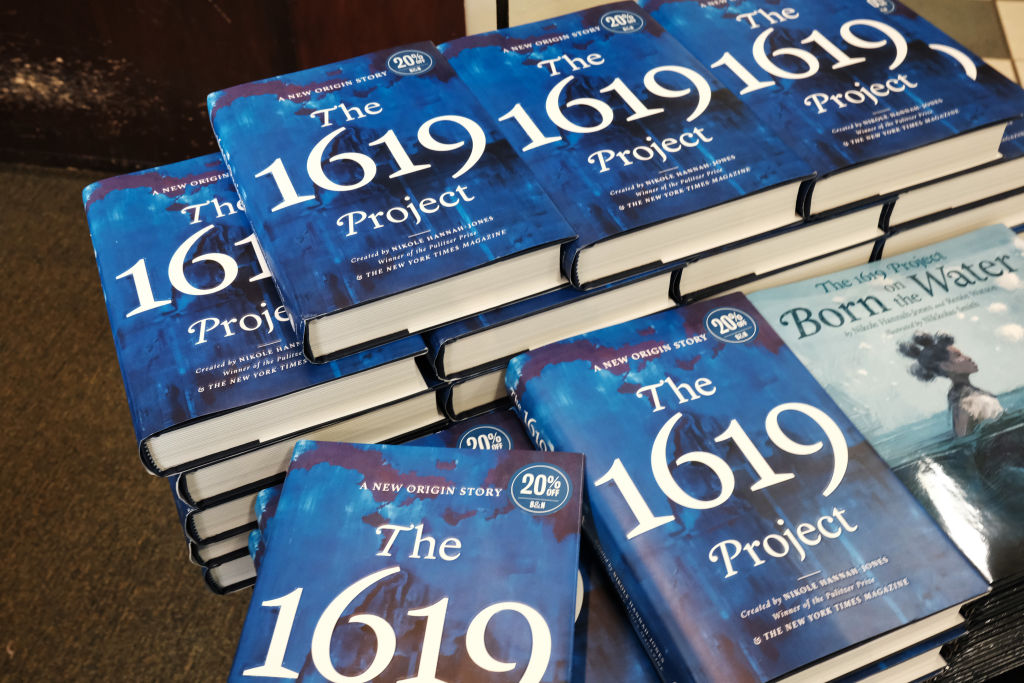

I decided to dig into one of the most vilified titles, “The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story,” edited by Nikole Hannah-Jones, Caitlin Roper, Ilena Silverman and Jake Silverstein and published by the New York Times and One World, an imprint of Random House/Penguin Random House. What I found surprised me.

The book is a series of historical essays arranged topically: Origins, Fear, Race, Democracy, Capitalism, Dispossession, Self-Defense, Sugar, Politics, Citizenship, Punishment, Inheritance, Medicine, Church, Music, Health Care, Traffic, Progress, Justice. Following each essay are literary pieces, often poems, that give a personal perspective on the essay’s topic. You don’t need to read them in order, although they are roughly chronologically arranged.

I am a scholar of African American History, earning a Ph.D. in American Studies from the University of Kansas in 1998, and I learned a lot from the essays.

I had spoken at KU with Carol Anderson of Emory University, author of the superb essay on Self-Defense. When I turned to the back to read her bio, I was struck by all the authors. Virtually every one of them had won Guggenheim Fellowships or MacArthur Genius Fellowships. These are the most coveted awards for scholarship, productivity and brilliance. From what I learned reading the essays, I could see why their authors had been selected to receive them.

Most Americans are oblivious to the fact that U.S. history through the early 1960s was considered the history of wars and presidents, white men almost without exception with nary a woman among them or a person of color.

– Gretchen Eick

Most Americans are oblivious to the fact that U.S. history through the early 1960s was considered the history of wars and presidents, white men almost without exception with nary a woman among them or a person of color. The Civil Rights Movement “woke” many young Americans to this major oversight, and that generation of scholars began researching what had been obscured. It wasn’t that historians had not studied African American History since the 19th Century; it was that those historians were usually Black people and not part of the white academy.

From the 1970s on, historians of diverse ethnicities were researching and writing about groups that had been left out of the American story: Black people, Indigenous people, Asian people, Mexican people, women. The pace of discovery of historical records has continued to produce new material.

Each discovery expands the body of knowledge. At the end of the 20th Century, for example, an African American novel written in French by a Black Louisianan in the 1830s was discovered in a Paris archive. Until that time, the body of knowledge identified novels written in English by Black Americans in the 1850s as the earliest African American novels, disregarding the Spanish and French past of the vast majority of U.S. land.

Multiply this one discovery by thousands and you can imagine how much new material now available to scholars and students, material that alters how we see our nation, its past and ourselves as part of the story.

If you are among the skeptics questioning whether this is merely “politically correct” history, take out “The 1619 Project” from your library and read some or all of the essays. “Sugar” and “Self-Defense” were two of my favorites. I guarantee you will learn a lot. And you will begin to understand why this history belongs to and should be taught to all Americans.

Gretchen Eick is an author, educator and publisher in Wichita. Through its opinion section, the Kansas Reflector works to amplify the voices of people who are affected by public policies or excluded from public debate. Find information, including how to submit your own commentary, here.