TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Ron DeSantis’ policies toward the Black community are coming under fresh scrutiny after an avowed racist gunman killed three Black people over the weekend at a Jacksonville Dollar General store, an attack the Justice Department is investigating as a hate crime.

The white gunman, identified as 21-year-old Ryan Christopher Palmeter from neighboring Clay County, had more than 20 pages of writings that expressed open racism toward Black people found by his parents after the 11-minute rampage, which included Palmeter taking his own life.

“I know for a fact that he did not like Black people,” Jacksonville Sheriff T.K. Waters said at a news conference to address the shooting. “He made that very clear.”

Florida’s Black community and beyond have been vocally opposed to the DeSantis administration’s focus on wiping out higher education diversity programs, the teaching of institutional racism to public school students, scrutinizing African American history courses and drawing a redistricting map that erased northern Florida’s only Black-performing congressional seat, which included the city of Jacksonville.

In May, the NAACP even issued a travel advisory for the state of Florida, over DeSantis’ “aggressive attempts to erase Black history and to restrict diversity, equity and inclusion programs.”

“How much can we allow the governor to keep his foot on our neck and not say anything?” said state Sen. Shevrin Jones, a Miami Democrat who is Black. “This is the result of that stuff. It’s not only the result, but it gives individuals who committed this act a hall pass to make it seem like it’s OK.”

Follow NBC News’ live coverage of the deadly shooting

Issues of race and education are part of a broader culture war agenda that has defined DeSantis’ time in office and been a hallmark of his 2024 presidential campaign. The agenda regularly has him at odds with civil rights leaders who say his “war on wokeness” is a thinly veiled attempt to go after people of color and other marginalized communities in the state.

“He has had an all-out attack on the Black community with his anti-woke policies, which we know very well was nothing more than a dog whistle to get folks riled up in a way it just happened yesterday,” state Rep. Angie Nixon, a Black Democrat who represents Jacksonville, told MSNBC on Sunday.

DeSantis on Sunday said he would step away from his presidential campaign to return to Florida to focus on the response to Tropical Storm Idalia, which is expected to turn into a hurricane over the next 24 hours.

DeSantis’ office did not return a request seeking comment for this article.

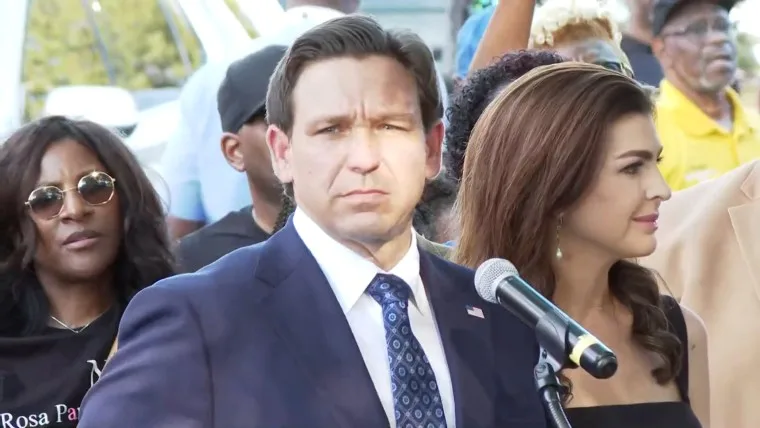

That mistrust between DeSantis and Florida’s Black community was on full display Sunday when the governor faced audible boos at a Jacksonville vigil for the three victims — jeering that continued until Jacksonville City Councilwoman Ju’Coby Pittman, a Black Democrat, asked the crowd to let DeSantis speak.

At the vigil, DeSantis called the gunman a “scumbag.” Jeffrey Rumlin, a Jacksonville pastor who spoke after DeSantis, was more direct.

“At the end of the day, respectfully, governor, he was not a scumbag,” Rumlin said. “He was a racist.”

On Monday, DeSantis pledged $1.1 million to help beef up campus security at Edward Waters University, a historically Black institution near where the shooting took place.

“We are not going to allow our HBCUs [historically Black colleges and universities] to be targets for hateful scumbags,” DeSantis said. “I have directed my administration to use every resource available to ensure the Edward Waters campus is safe following this shooting and to help the impacted families as they mourn their loved ones.”

Jones said he is not impressed that DeSantis went to the vigil. He pointed out that DeSantis, then a congressman, also visited the scene of the Pulse nightclub massacre in Orlando in 2016, which left 49 people dead.

“He was there, and it did not change his response to the LGBTQ community. Him showing up in Jacksonville looked like a political stunt from someone running for president,” Jones said. “You can’t take three or four years of his actions and then show up to the Black community saying, ‘I stand with you.’ No, you don’t.”

The key to the DeSantis administration’s focus on the Black community has been in education, where he has pushed legislation banning diversity and equity programs in Florida’s higher education system, was among the first Republicans nationally to push for bans on critical race theory — the study of how systematic racism affects American society — and faced fierce pushback after his administration rejected an Advanced Placement African American studies course.

Most recently, DeSantis doubled down in defense of his Department of Education releasing education standards that include the idea that some Black people received some “personal benefit” from slavery.

For weeks, as he was trying to reset his presidential campaign after a slow start, DeSantis insisted that some slaves learned skills like how to become a blacksmith while enslaved. That position earned him a torrent of criticism from people who said the move was just another in a long line of politically motivated slights toward the Black community.

The DeSantis administration’s insistence on including the curriculum drew bipartisan rebukes, including from a number of Black Republican congressmen. Among the most notable was Rep. Byron Donalds of Florida, who was a longtime DeSantis ally but has now endorsed Donald Trump’s presidential campaign.

“The new African-American standards in FL are good, robust, & accurate,” Donalds tweeted in July. “That being said, the attempt to feature the personal benefits of slavery is wrong & needs to be adjusted. That obviously wasn’t the goal & I have faith that FLDOE will correct this.”

The tweet prompted several days of DeSantis supporters going after Donalds on social media, and framing the governor’s detractors as sympathizers of Vice President Kamala Harris, who traveled to Jacksonville to blast the new curriculum suggestions in the days after they became public.

“These extremist, so-called leaders should model what we know to be the correct and right approach if we really are invested in the well-being of our children,” she said at the event at the Ritz Theatre and Museum, which is in one of the city’s predominantly Black neighborhoods.

It’s not the first time Jacksonville has played a role in the at times open hostility between DeSantis and the state’s Black residents.

During the state’s 2022 redistricting process, maps drawn by DeSantis’ office erased northern Florida’s only Black congressional seat, which ran from Tallahassee to Jacksonville and was represented by Black Democrat Al Lawson, who lost re-election in a newly configured seat. The new map boosted the number of GOP seats in Florida’s 28-member delegation to 20, and helped Republicans maintain a slim majority in the House after a disappointing 2022 midterm cycle.

The state’s new congressional map sparked an immediate legal challenge from a coalition of groups, including Black Voters Matter, Equal Ground, and the League of Women Voters of Florida, who said the changes disenfranchise voters in northern Florida — a region that included several slave plantations — and violated Fair Districts, amendments in the state constitution that dictate new seats can’t “diminish” minority voters’ ability to elect someone of their own choosing.

During a four-hour court hearing last week in Tallahassee, Circuit Judge Lee Marsh openly expressed skepticism toward the state’s arguments about getting rid of the northern Florida seat.

The April 2022 passage of those maps sparked a sit-in on the Florida House floor led by Nixon, the Jacksonville Democrat, along with other Democratic lawmakers who wanted the Republican majority to draw a new congressional map that included a Black-performing north Florida seat.

“What we have here is a group of people who are worried and concerned and scared about the browning, about the darkening of our country,” Nixon said at the time. “They are trying to hold on to power so much that they are changing the rules.”