The state of Florida is fighting back against a court decision that struck down a redistricting plan pushed by Gov. Ron DeSantis, announcing this week that it is appealing the ruling.

The notice of appeal, filed Monday by Secretary of State Cord Byrd, had been widely expected in response to a state judge’s decision Saturday in the legal battle over Florida’s congressional map. The appeal also puts the judge’s ruling on hold.

The new map, which was drawn last year, erased a congressional seat for a district where 46% of voting-age residents were Black. Al Lawson, a Black Democrat, represented the district and promptly lost re-election in the newly drawn seat.

The plan also increased the number of GOP seats in Florida’s 28-member delegation.

In his opinion, Circuit Judge Lee Marsh wrote that the DeSantis-approved map violated the state constitution by “diminishing the ability of Black voters in North Florida to elect representatives of their choice.” He ordered the Legislature to draw a new one.

Marsh’s ruling was a victory for voting rights advocates — including Black Voters Matter, Equal Ground and the League of Women Voters of Florida — who sued the state, saying the new map violated the state’s Fair Districts Amendments, which stipulate that new seats can’t “diminish” minority voters’ ability to elect politicians of their choosing.

The advocates argued that the new map was the reason Lawson failed to get re-elected last year, when he lost by nearly 20 points.

“You can’t take away a district or retrogress a district that allows for minority voters to elect a member of their choice,” said John Bisognano, the president of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, which has been supporting plaintiffs.

In a February 2022 memo, DeSantis and his office called the stretch of land previously known as the 5th District — housing the state’s only majority African American county — an example of a “racial gerrymander.” Two months later, at an April news conference, he promised: “We are not going to have a 200-mile gerrymander that divvies up people based on the color of their skin. … That will be litigated.”

DeSantis’ office intervened in the redistricting process, rejecting a map created by the Legislature and coming up with one that erased the Lawson district. DeSantis called a special legislative session and used his veto power to ensure his version was implemented.

Civil rights lawyers like Cecile Scoon found his actions surprising at the time and further disappointing once the Legislature capitulated.

“In the past, governors have kept their hands clean,” said Scoon, who is also a co-president of the League of Women Voters of Florida. “They’ve not drawn their own maps. … The governor’s actions were incredibly aggressive.”

Now, with the state’s appeal, the case heads to the Florida Supreme Court, which has a majority of conservative DeSantis-appointed members.

Despite the plaintiffs’ celebration over the weekend, Harvard law professor Nick Stephanopoulos said it is far from a done deal.

“It’s totally routine in redistricting cases for plaintiffs to win at the trial court level and then to have some higher court reverse the decision,” he said.

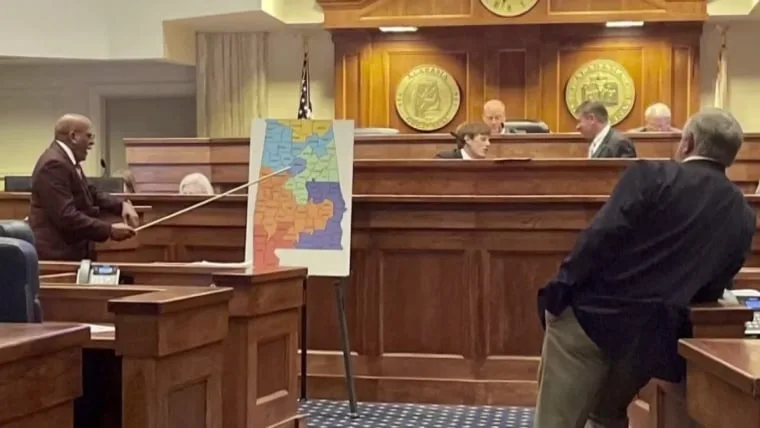

Bisognano said that with redistricting battles simultaneously making headlines in states like Alabama, Louisiana and Georgia, map challenges are the new normal.

“We have absolutely entered an era of perpetual redistricting. It’s a new time,” he said. “It’s a new moment in which we’re going to be continuing to fight these fights over the course of the decade instead of just a year or two years after a census.”

As for the case in Florida, both sides say they are eager to expedite the process to have their versions of a map ready in time for the 2024 elections.

Republicans have a narrow 222-212 lead over Democrats in the state House, and the outcomes of the latest congressional map battles could have big implications in Congress’ balance of power.