Black women account for one in seven women in the U.S. today and play an integral part of our workforce and communities. Despite making significant advances and contributions to U.S. society, Black women continue to face high levels of unfair treatment and systemic discrimination, making up disproportionate shares of people living in poverty and working in low-wage jobs. Reflecting the intersectional nature of their identity, Black women experience the combined impact of discrimination based on their gender in addition to their race. KFF’s 2023 Racism, Discrimination, and Health Survey is a major effort to document the extent and implications of racism and discrimination, particularly with respect to people’s interactions with the health care system. As reported in the overview report, a majority (54%) of Black women say they experienced at least one form of discrimination asked about in the survey in the past year, such as receiving poorer service than others at stores or restaurants.

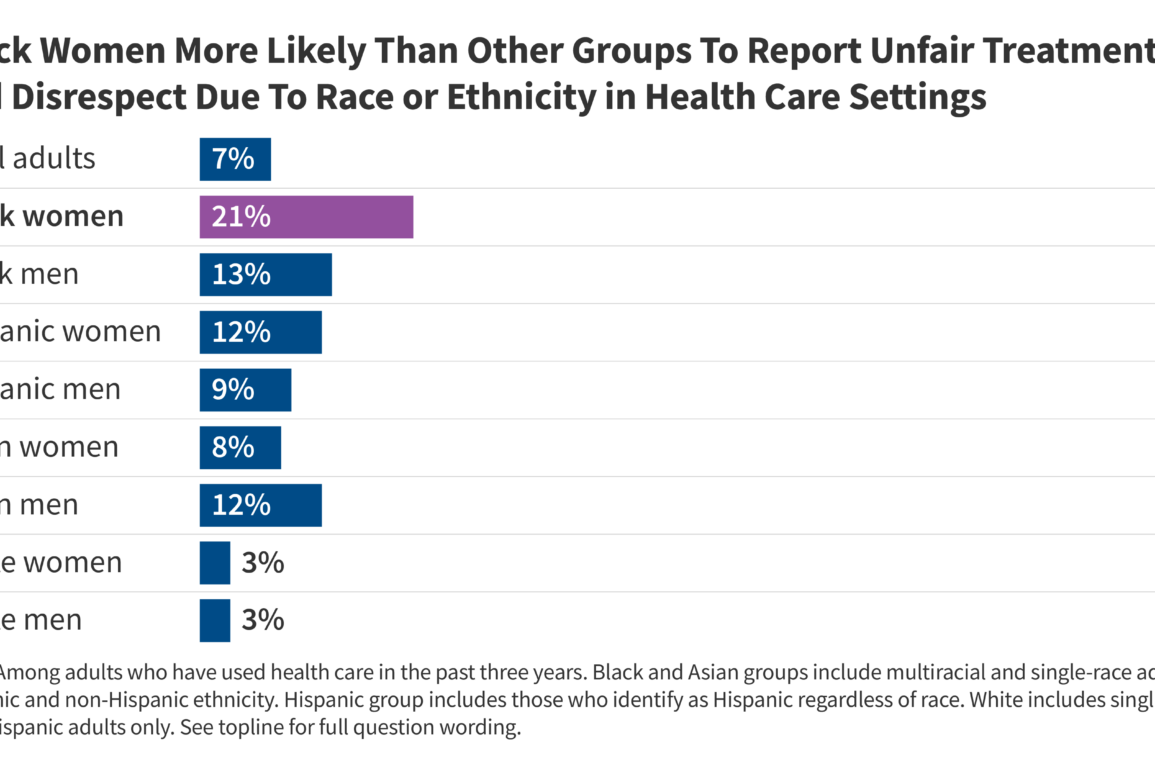

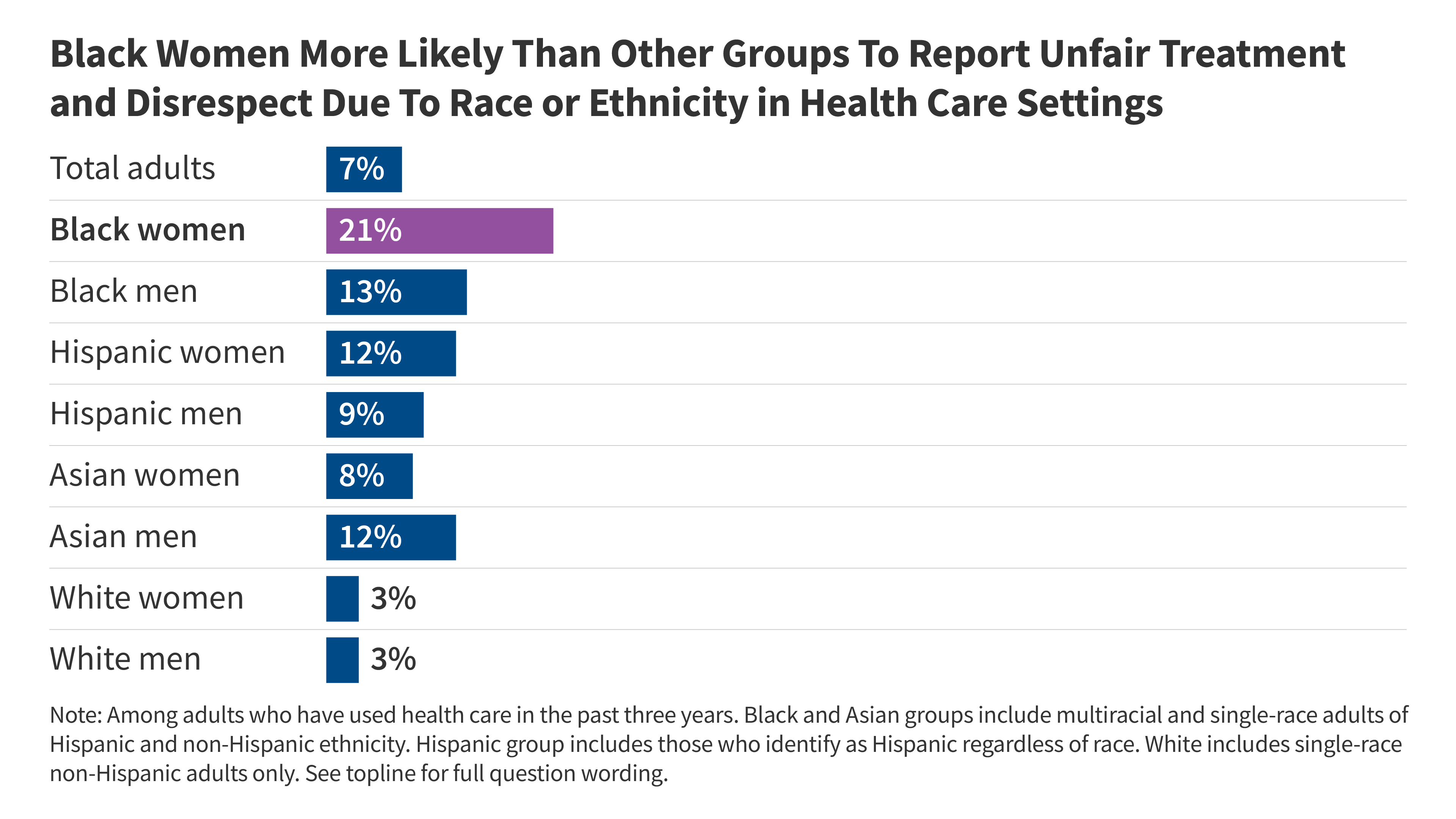

In addition to these everyday forms of discrimination, Black women also report experiencing disproportionate levels of unfair treatment in health care settings. For example, about one in five (21%) Black women say they have been treated unfairly by a health care provider or their staff because of their racial or ethnic background and a similar share (22%) of Black women who have been pregnant or gave birth in the past ten years say they were refused pain medication they thought they needed. These experiences may contribute to ongoing disparities in health for Black women, including stark divides in maternal health.

Below are five key facts about Black women’s experiences in health care drawing on the survey. The findings highlight that while overall most Black women report positive interactions in health care settings, experiences with discrimination and unfair treatment due to race are pervasive among Black women of all backgrounds. Having more health care visits with a racially concordant provider is associated with increased reports of positive experiences in health care settings among Black women, illustrating the opportunities to increase high-quality and culturally competent care which may mitigate disparities in health.

Although overall most Black women report positive experiences receiving health care, they are more likely than other groups to report being treated unfairly by a health care provider due to their race and ethnicity and to say they prepare for possible insults or must be very careful about their appearance to be treated fairly during health care visits. Overall, similar to other groups, the majority of Black women report positive interactions when receiving health care in the past three years, such as a doctor spending enough time with them during their visit or explaining things in a way they can understand. However, compared to other groups, Black women are more likely to report being treated unfairly by a health care provider in the past three years. For example, Black women (21%) are more likely to say they have been treated unfairly by a health care provider because of their racial or ethnic background than are Black men (13%) and are seven times as likely to say this than are White women (3%). In another example, about six in ten (61%) Black women say they are very careful about their appearance or prepare for possible insults when seeking health care, similar to the share of Black men (57%), but roughly twice the share of White men (28%) who say the same.

Reports of unfair treatment by a health care provider due to race and ethnicity persist among Black women with higher incomes and are particularly high among those who are younger and those with darker skin tones. Across income groups, at least one in six Black women say they have felt they were treated unfairly or with disrespect because of their race or ethnic background during a health care visit in the past three years. There are some differences in experiences with unfair treatment among Black women by age and skin tone. Younger Black women are more likely than older Black women to say they have had this experience, with about a quarter of Black women ages 18-29 (23%) and 30-49 (26%) and one in five ages 50-64 (19%) reporting this compared with about one in ten (11%) Black women ages 65 and over. Black women who describe their skin tone as “very dark” or “dark” are also more likely to report these experiences compared to those who describe their skin tone as “light” or “very light” (27% vs. 17%).

Black women who are younger or who have self-reported darker skin tones are more likely than their counterparts to say they prepare for possible insults or feel they must be very careful about their appearance to be treated fairly during health care visits. Vigilant behaviors, such as preparing for insults or considering one’s appearance, are sometimes adopted by people who experience discrimination as a means of protection from the threat of possible discrimination and to reduce exposure. Research has shown that heightened vigilance is associated with poor physical and mental health outcomes, including hypertension, sleep difficulties, and depression. While about half or more Black women regardless of income, age, and skin tone say they do one or both of these things at least some of the time, the share of Black women who report these vigilant behaviors is higher among those who are younger and have darker skin tones. For example, seven in ten (71%) Black women with self-reported darker skin tones say they have to be very careful about their appearance and/or prepare for insults at least most of the time, whereas about half (56%) of Black women with self-reported lighter skin tones say the same.

About one in three (34%) Black women who used health care in the past three years report that a negative experience with a health care provider resulted in worse health (13%), them being less likely to seek care (19%), and/or them switching providers (27%). Younger Black women are more likely than those ages 65 and over to report that a negative experience resulted in one of these consequences. In addition, Black women who describe their own physical and/or mental health as “fair” or “poor” are more likely than those who report better health to say that a negative experience resulted in worse health, being less likely to seek care, or switching providers in the past 3 years.

Black women who had at least half of their health care visits with a racially concordant provider report more positive interactions with their health care providers. For example, Black women who had at least half of recent visits with a provider who shares their racial or ethnic background are more likely than those who have fewer of these visits to say that their doctor spent enough time with them during their visit (80% vs. 66%), explained things in a way they could understand (90% vs. 82%), involved them in decision-making about their care (84% vs. 76%), understood and respected their cultural values or beliefs (84% vs. 75%), or asked them about social and economic factors (39% vs. 27%) during recent visits. However, about six in ten (63%) Black women say that less than half or none of their health care visits in the past three years have been with a provider who shared their racial or ethnic background. This suggests that increasing the diversity of the health care workforce may help increase positive interactions for Black women and points to importance of training and education among all providers to provide culturally competent and respectful care.