Our blended family took our very first road trip this Thanksgiving weekend to visit my wife’s father and stepmother in Memphis. The trip meant everything, as it was the last Turkey Day holiday with all four of us — my wife, children and myself — living under one roof.

Our 18-year-old twins, whom I inherited through marriage, are about to go away to college next year. Although I have only been their stepdad for almost two-and-a-half years, I feel excited for them as young Black people who will encounter the so-called “real world” with ample intelligence and opportunity within their grasp.

They are also fortunate, having been raised by a village of successful Black professionals with resumes, achievements, degrees and lifetimes upon lifetimes of wisdom and experience. They have a clear and distinct advantage over many of their peers, regardless of color.

But like every parent with teenagers about to meet the world head-on, I am fearful and protective over their lives. It’s hard for me and my wife to rest because we see the monsters under the bed they have yet to encounter.

In this country, there are forces at work that make denying, diminishing and disqualifying young Black people from opportunity a sport.

![]()

For as many kids of color who go on to succeed thanks to supportive, nurturing environments, countless others see their luminous potential dimmed because they had to contend with toxic and racist gatekeepers and environments.

For instance, they will go on job interviews where, no matter how many degrees, academic honors or qualifications they have, those things won’t really matter as much as the color of their skin or who they know.

Even when they get jobs or start their own businesses, there will be no panacea, no remedy for the problems they will encounter in adulthood.

But I am getting ahead of myself, way ahead.

I’m basing these assertions on my experiences, just as my parents did to me. But we know that to grow up Black in America is to face obstacles, racial resentments and prejudices that run on repeat like a syndicated TV sitcom, the same horrid show of racial hatred, marginalization and oppression playing on a loop, generation after generation.

To paraphrase the great James Baldwin, to be Black in America “and conscious is to be in a state of rage almost all of the time.” Indeed.

I would add the word “anxious” to that statement. It’s the kind of anxiety bred by this knowing that things could go left even amid a pleasant experience, even when you do good and play by the rules.

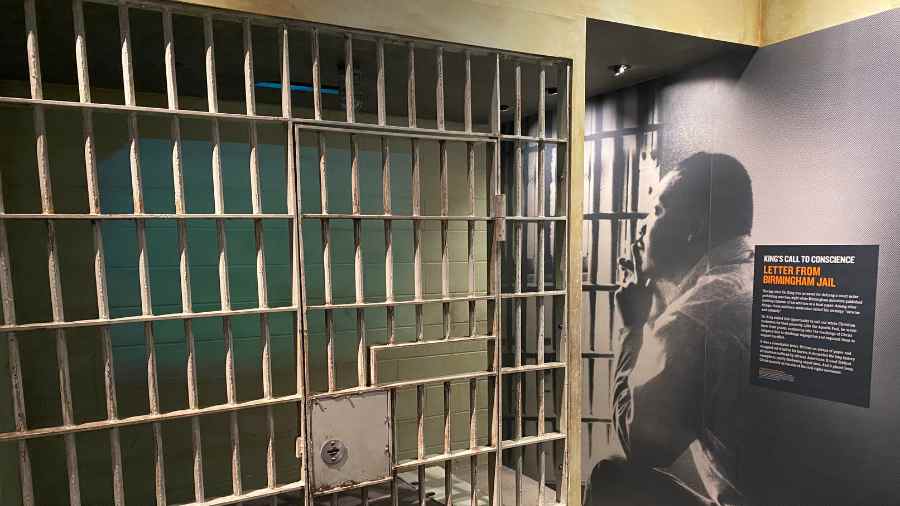

This anxiety was present for me when, on that same Thanksgiving holiday trip, we visited the National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel, the site where Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated.

When my wife and I first saw the iconic motel sign and the balcony where King was struck, with its faded aqua-blue railing, our stomachs were in knots.

I couldn’t help but wonder what this visit would mean to our teenagers, who are months away from leaving us.

For Our Children, Can the Hope Outweigh the Fear?

In an era when African American history is being whitewashed and legislated out of classrooms, the National Civil Rights Museum is an invaluable resource as it tells the story of Black people in America, from slavery to present times.

From the lynching of Emmett Till to the rise of the Black Arts Movement, the museum provides a baseline understanding of the influential events and figures that shaped the Civil Rights movement and the African-American struggle in America in general.

A history lover will likely know all about the events the museum covers and is likely to scrutinize each exhibit, looking for details that may have been left out.

But even the most astute scholar would be moved by the anecdotes of the individuals who lived through these incidents.

An exhibit dedicated to the Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954 features a row of wooden desks against a wall of full-sized photos of Black children in classrooms.

Embedded in each desk are artifacts from the period after the decision, when schools in states like Arkansas were slow to comply with the federally mandated decision to desegregate. They specifically chronicle the lives of the first Black students to enroll at Little Rock’s Central High School.

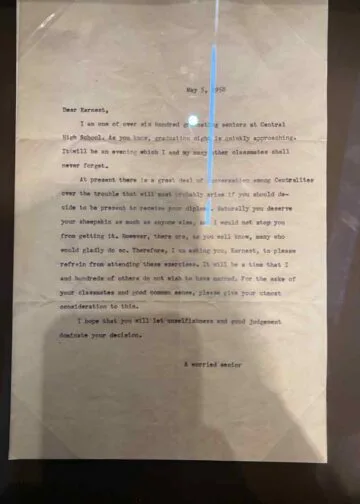

There is a typed letter dated May 5, 1958, from “a worried senior” to a student named Ernest Green, one of the nine Black teens at Central High known as the “Little Rock Nine.”

A White student pleaded with Green not to attend his own graduation and receive the high school diploma he was entitled to. The writer also misspelled his name.

“Naturally, you deserve your sheepskin as much as anyone else, and I would not stop you from getting it. However, there are, as you well know, many who would gladly do so,” wrote the concerned student.

“Therefore, I am asking you, Earnest, to please refrain from attending these exercises. It will be a time that I and hundreds of others do not wish to have marred.

The “worried senior” ends the letter this way: “I hope that you will let unselfishness and good judgement [sic] dominate your decision.”

Melba Patillo Beals, the daughter of one of the first Black graduates of the University of Arkansas and one of the “Little Rock Nine,” wrote about the daily abuse she endured while also attending Central High School.

One of the most flagrant incidents occurred when Beals was sitting in a bathroom stall, and a White female student dropped burning paper on her.

“I don’t know if I could put my children through that,” my brother-in-law’s wife said as our families wound their way through the exhibit.

“Me neither,” I said.

It made me wonder what drove the parents of those students to agree to have their children endure that hostility and hatred. Did the hope of a better education outweigh their trepidation over the hate and violence they faced?

Will my hope and optimism over my children’s futures be enough to eclipse the utter fear I still hold for them over a world where history and racist incidents repeat?

‘Heavy but Good’: Choosing Hope Amid the Silence

The National Civil Rights Museum tour concludes at the two Lorraine Motel rooms where Martin Luther King, Jr. and his party dwelled just before his assassination. One room contained a full-sized bed, and Room 306, where King stayed, had two twin beds.

An informational display recounts the well-known story of King being in a cheerful mood when he stepped out onto that balcony and asked saxophonist Ben Branch to play his favorite hymn, “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” at a meeting later.

Seconds later, a bullet struck him in the neck. Some accounts say it was his right jaw.

When we finished the tour and stepped outside, a staff member directed my family to a metal line embedded in the ground that crossed the width of the walkway, leading toward the balcony where King stood. The line, he said, represented the trajectory of the bullet.

He also directed our attention to a rooming house across from the Lorraine Motel where one of the three windows was slightly cracked. That was where the alleged shooter, James Earl Ray, fired the shot, he said.

On the drive back, the car ride was mostly quiet.

My wife asked the kids what they got from the tour.

“Heavy, but good” was the consensus. But with teenagers, their silence, what they choose not to say, always echoes loudly.

I thought each exhibit reinforced the fact that this country was not only unwilling to provide Black people equal access to opportunity but that even now — through its systems, politics and institutions — seems unwilling to recognize our personhood or grant us the full complement of rights and reparations we deserve. The tour remained a clarion call for all of us to keep fighting for justice, love, access, restoration and wholeness.

But I kept those thoughts to myself, opting for silence too.

With their graduations inching closer by the day, what matters more is that my wife and I’s hopes can keep those monsters at bay.

Here are some more photos from our trip:

The opinions expressed in this column are the writer’s and do not necessarily reflect those of The Chicago Defender.