- Over 1,800 families in the Chavez Ravine were promised public housing before city officials abandoned the plans to build Dodgers Stadium

- Lawmaker Wendy Carrillo introduced a reparations bill to ‘address the historical injustice’ they faced

A California state lawmaker has vowed to have reparations paid to over 1,800 families who were displaced by the building of the Dodgers Stadium.

Democrat Assemblywoman Wendy Carrillo introduced her bill, AB50, to ‘address the historical injustice’ of the building of the famous baseball stadium in the 1950s.

The throng of families kicked out of their homes in LA’s Chavez Ravine were predominantly Latino, and were led to believe they would return to improved public housing before the stadium was built on their properties instead.

‘Families were promised a return to better housing, but instead, they were left destitute,’ Carrillo said.

The area that now hosts the Dodgers Stadium, Chavez Ravine, spanned over 300 acres and was ‘home to generations of predominantly Mexican Americans’, Carrillo said.

She argued that those families who lost their homes are entitled to reparations as they were unceremoniously booted out by Los Angeles officials.

The city acquired the land through eminent domain intended to be used to rebuild improved public housing in the early 1950’s, a move that displaced thousands of families.

The project, named Elysian Park Heights, would have consisted of 20 apartment buildings and over 160 townhouses, as well as schools, a college and playgrounds.

Officials later rejected the plans and decided to sell the land to a private developer, who built the Dodger’s Stadium in the spot.

Construction began in 1959 and ended in 1962, costing $23 million at the time – the equivalent of over $236 million today.

However, getting the construction off the ground was far from easy, with almost all of the families in the area initially refusing to move – and some held out for years.

Early in the 50s, some families landed deals to sell their homes directly, before offers were reduced gradually to spark panic among those hoping not to move out.

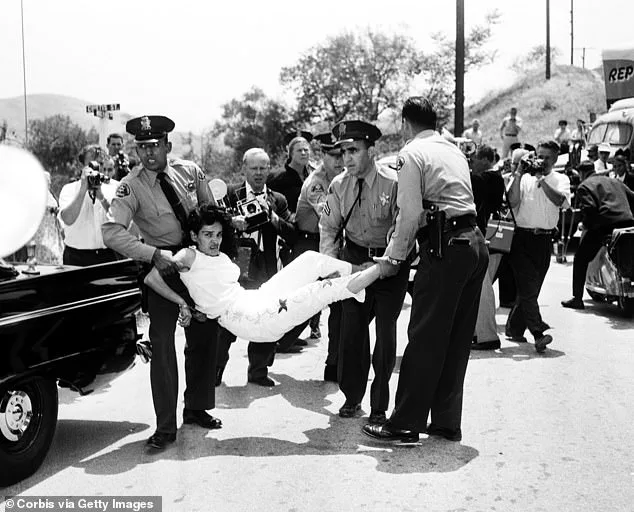

By May 1959, Los Angeles County Sheriff’s deputies were brought in to remove the last of the stragglers, as some vowed never to leave their homes.

This led to an infamous image of Aurora Vargas being hauled out of her home by deputies, kicking and screaming from her property.

Carrillo cited such scenes in a press release pledging reparations for displaced families, who were left ‘destitute’ though no fault of their own by the forced move.

Her bill is reportedly backed by the Buried Under the Blue organization, which says it works for justice for the families who were ‘forgotten and wrongly evicted from their homes and land.’

Alongside monetary reparations, the legislation would also construct a permanent memorial, and proposes ‘various forms of compensation, including offering City-owned real estate comparable to the original Chavez Ravine landowners or providing fair market value compensation adjusted for inflation.’

‘It also creates pathways for displaced non-landowning residents to receive relocation assistance, healthcare access, employment support, educational opportunities, and other forms of compensation deemed appropriate by a newly established Task Force,’ Carrillo’s press release said.

The lawmaker added at a press conference: ‘For generations, Chavez Ravine stood as a beacon of hope and resilience, embodying the dreams and aspirations of families who built their lives within its embrace.

‘With this legislation, we are addressing the past, giving voice to this injustice, acknowledging the pain of those displaced, offering reparative measures, and ensuring that we honor and remember the legacy of the Chavez Ravine community.’