This story originally published online at The Guardian.

Alex Fields had not spoken to his nephew in four years. Not since the killing.

He had been preparing himself for months. Speaking with his counselors and siblings, seeking guidance from his church as he ran through what their first conversation would be like. But when his nephew Donald Fields Jr. finally appeared over Zoom from the county jail, Alex Fields was consumed by the moment.

“It just brought back all the memories,” he said. “It brought back that entire day.”

Don Jr. was charged with the murder of his father, Donald Fields Sr., in 2016. He faced a possible life sentence and had not spoken to members of his family since he was taken into custody in June that year. But today was the first step in a long journey that would see a tragedy transformed into a pioneering case of compassion in America’s punitive criminal justice system. It marked the first time that restorative justice—the act of resolving crimes through community reconciliation and accountability over traditional punishment—had been used in a homicide case in the state of North Carolina. And probably the first case of its kind in the US.

“Hey Don, how are you doing?” Alex Fields remembered saying to his nephew. “It’s been a long time.”

“Hey,” Don Jr. replied, holding back tears, “it’s good to see you.” He had never been known in the family as much of a talker.

“I just want you to know that what you did was horrific,” Alex said. “It’s been four years and your entire family is still suffering.”

“But I have to forgive you. I want to forgive you. And I want you to forgive yourself.”

It had taken Alex Fields the better part of three years to forgive his nephew.

Alex remembered seeing Don Jr. at his first court appearance the day after the killing. He had appeared in the Durham county court wearing an orange jumpsuit, his wrists shackled, avoiding eye contact while members of his family sat in disbelief, watching from the public benches.

Alex was shellshocked. It was a violent, bloody killing that had happened over something so seemingly banal that he could not fathom it.

According to prosecutors, Don Jr., then 24, had stabbed his father with a folding pocket knife during an argument triggered by the placement of a television set. It happened at the home they shared with other members of the family. The two had briefly argued and Don Sr., 54, had threatened to beat his son and kick him out of the home. That’s when Don Jr. pulled the knife.

An autopsy found 18 lacerations on Don Sr.’s body, including wounds to his heart, lungs, and humerus bone. The killing left the living room sprayed with blood, staining the carpet, the walls, and the chairs.

Lessie Vivian McGhee-Fields, Alex’s mother and the family’s matriarch, had been in her bedroom. At 93, she had dementia and was permanently bedbound. Her son had been killed by her grandson in the living room of her own home, one she had acquired through hard work and selfless sacrifice over many decades.

The thought of his mother, alone in her room while the whole thing happened, would come to haunt Alex. She was left for hours on her own in the house as the police cordoned off the scene.

Don Jr. had fled almost instantly. His cousin Brandon, who had witnessed the stabbing, had sprinted up the road to the local church where family members were wrapping up a Sunday service. They called 911. Hours later, Don Jr. turned himself in at a gas station as news of the murder blared on local television. He still had the knife in his possession.

As Alex sat in court the next day, watching his nephew bow his head, forgiveness was far from his mind. He was irate. And he couldn’t comprehend any of it.

As he tried to make sense of the situation, the familiar cogs of the legal system had already begun to turn, and Don Jr. was facing decades locked away.

It was one of 45 homicides in Durham that year.

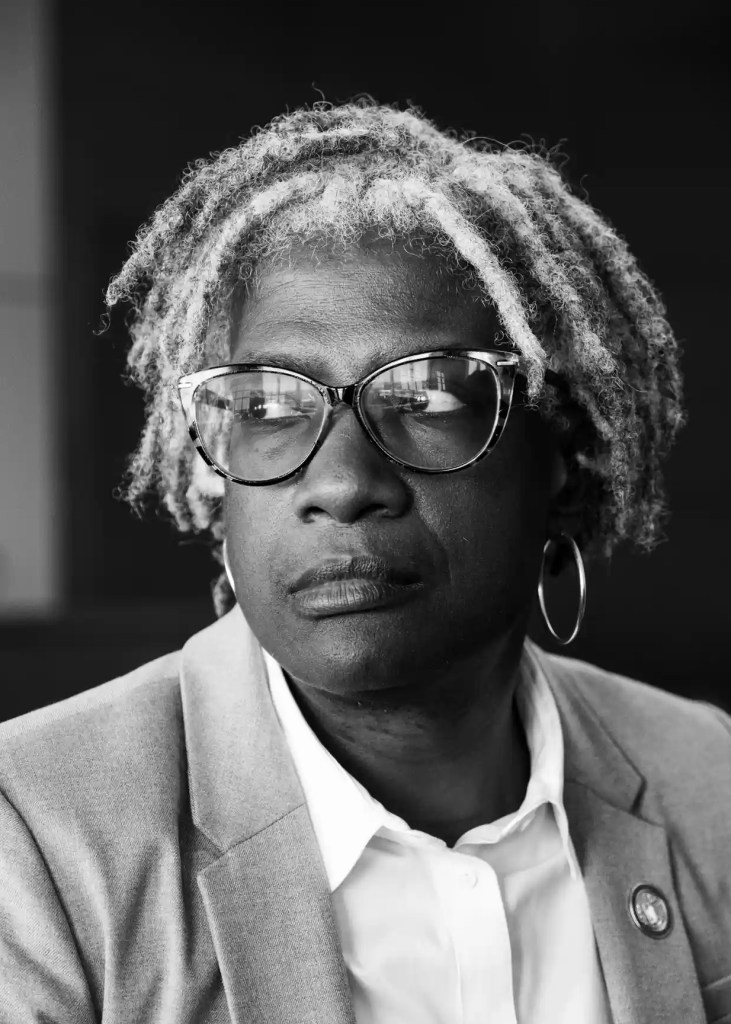

As a former defense attorney and the leader of a fair housing coalition, Satana Deberry was not a typical candidate for the job of top prosecutor. But her primary victory in May 2018 was decisive and seen as a bold move towards progressive reform in this left-leaning city, which sits in the center of North Carolina and is dotted with college campuses and tall church steeples.

“We need a culture change in Durham,” Deberry said during the campaign for district attorney. “We can’t continue to call ourselves the most progressive city in the south and over-prosecute people.”

Despite its liberal facade, Durham’s DA’s office has been marred by a series of scandals in recent years, from misconduct allegations and disbarments to wrongful convictions and the use of junk science during high-profile prosecutions. The city had cycled through six district attorneys, most career prosecutors, in just 12 years before Deberry’s election.

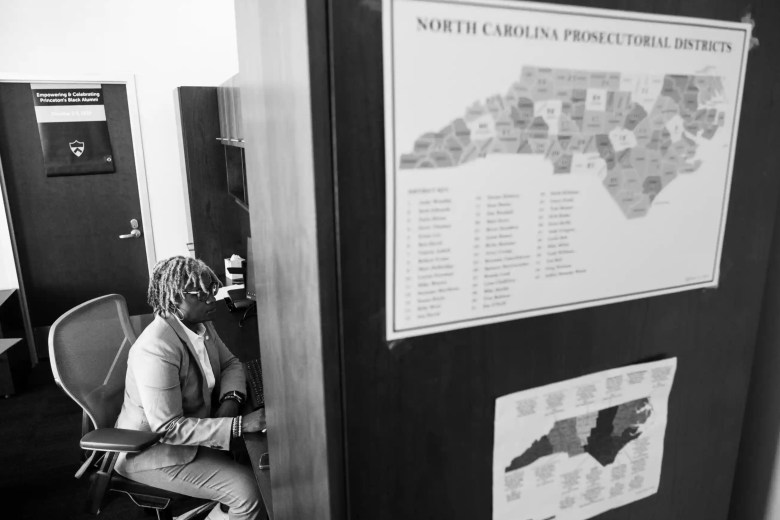

“For this community, there was no real continuity,” she said one recent afternoon at her office on the eighth floor of Durham’s towering courthouse. “No idea who was in charge, much less how the office worked.”

Her campaign centered on transparency and the need to address the racial bias underpinning America’s mass incarceration epidemic. She sought reforms to the bail bond system, to limit the prosecution of juveniles as adults, and for greater use of restorative justice throughout the office. All are clarion calls that have echoed throughout the country as a wave of progressive prosecutors won elections in the wake of the prolonged racial reckoning after the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri.

There had been informal use of restorative justice in Durham’s criminal legal system before Deberry’s election, mostly confined to misdemeanor offenses. But just a few weeks before her victory, the office concluded its first use of the process in a felony case.

The incident involved the accidental shooting of an 11-year-old girl, who was injured after a single bullet struck her from above while she lay in bed. The offender, a man named James Berish, had been unloading a stolen handgun in his apartment when it accidentally discharged, piercing the floor. When he heard a child had been shot below him, Berish, a young father, handed himself in to the police and helped them recover the gun. He had faced up to 10 and a half years in prison, but was instead given two years probation after the family opted to pursue restorative justice. The sentencing occurred after a year-long process, which led to him apologizing to the girl in person and offering restitution, including the purchase of a new bed and a basket of art supplies requested by the girl, a keen artist.

The case was handled by a long-serving Durham assistant prosecutor named Kendra Montgomery-Blinn, one of the office’s earliest proponents of restorative justice. It taught her a number of lessons about how the process could work in cases of serious violence; that patience and time was a necessity, that prosecutors rarely knew all that victims wanted after a crime, and that accountability could extend beyond the parameters of a custodial sentence.

“I learned that the healing from the restorative justice process is more complete for survivors,” Montgomery-Blinn said. “They feel far more heard and involved.”

After the Berish case concluded, Montgomery-Blinn thought about another case she had been assigned two years previously, which was still mired in the adversarial formalities of a murder prosecution: the killing of Donald Fields Sr.

In July 2019, members of the Fields family filed into the DA’s office on the eighth floor.

They had been meeting regularly as the case progressed slowly through the system and had sat with Montgomery-Blinn to run though sentencing grids, where a charge and its commensurate punishment are laid out, as the DA carried out the standard process of navigating a plea deal to offer.

They had settled on a 20-year minimum sentence for a plea to second-degree murder, meaning a killing committed “utterly without regard for human life” but without premeditation.

Some members of the family wanted harsher punishment. Another of Don Sr.’s siblings had written to the presiding judge, describing the killing as a “monstrous/gruesome crime” and urging them to hand down “the maximum amount of years … without the possibility of parole”.

Nonetheless, the plea offer had not been accepted by defense, and the case was now moving towards a lengthy trial—a prospect Alex Fields was dreading. At the end of the process, Don Jr. could have received far more than 20 years of incarceration.

But on this summer’s day, Montgomery-Blinn took the first unorthodox step in the state’s handling of the case. She had sought permission from Don Jr.’s defense to share with the family a psychological evaluation his attorneys had commissioned. It was not, in her opinion, a piece of evidence that would change an outcome at trial, but it contained partial answers to some of the questions the family had been asking about why the killing had happened.

The document is not public, and the public defender who represented Don Jr. declined to be interviewed. But Alex Fields described it as an account of anger management issues his nephew had faced, and of a mental maturity that did not match his age.

The prosecutor left Alex and his two sisters alone to read.

“It read true,” Alex recalled.

He thought about previous episodes of violence he had witnessed between his brother and nephew, which had happened sporadically for five years before the killing. They would go at it “like a boxing match” on occasion, Alex said. Further, his nephew would have witnessed the physically abusive relationship between his parents before their separation when he was six years old.

Those who are victims of violence are far more likely to become perpetrators of violent acts later on.

“I knew that anger [in the report] was part of his childhood,” Alex said. “Naturally, he would have had anger.”

He thought too about how Don Jr. had left school before graduating. How he had never really found work and had remained dependent on his father, an electrician, into early adulthood.

“My brother, it was almost like he didn’t want his son to grow up.”

But he knew too that Don Jr. and Don Sr. loved each other deeply. “They really, really did when they weren’t fighting,” he said. “They were like two peas in a pod.”

After Alex and his two sisters digested the report, Montgomery-Blinn reappeared.

She asked if they would be interested in bringing the case through a restorative justice process. She explained how it might work—that the DA’s office would approach Don Jr.’s attorney to see if he would participate. That their conversations (or circles, as they are called) would occur away from prosecutors and defense lawyers, sanctioned by a court, but not within one. There would be no preordained outcome.

She told them that a local minister named the Rev. Annette Love—a facilitator with a group called Restorative Justice Durham—was sitting in the room nearby should they wish to proceed.

“I do not want to lose him [Don Jr.] to the system,” Alex said as he wept. “I do not want him to be another statistic. He would be swallowed up. So often, Black men, when they go to prison, they throw away the key or do not rehabilitate them.

“He can be rehabilitated.”

The Fields family agreed to move forward.

The Durham DA’s decision to offer restorative justice in violent felony cases makes the office an outlier in the US south, said Mona Sahaf, who monitors the expansion of the practice around the country as director of the Vera Institute of Justice’s reshaping prosecution initiative.

Sahaf pointed to comparable programs in Boston, Washington DC and Oakland but added that use of restorative justice in homicide anywhere in the country was “incredibly rare.”

“When we’re dealing with homicide cases, the pain and trauma for families is incredibly high,” Sahaf said. “Because you have lost a person you love so dearly for ever.”

“Victims want to feel some sense of control, and they want to feel some feeling of healing. And unfortunately our system doesn’t offer anything apart from criminal charges. We are taught from a very young age that justice in America means a criminal conviction. It means prison.”

Although principles of restorative justice have existed for centuries in ancient and Indigenous societies, its modern-day pioneer in the U.S. is Danielle Sered, who founded the Brooklyn-based organization Common Justice—the first in the country to help implement victim-influenced alternatives to incarceration in violent crimes. Still, the group does not take on homicide cases.

Sered, a sexual assault survivor, argues that in order to address the crisis of mass imprisonment, which has so disproportionately affected Black Americans, the narrative around justice reform must move on from solely addressing non-violent and drug-related offenses. Over half of those in America’s prison system have been locked away over acts of violence, so how can the world’s most incarcerated country engage in meaningful reform without addressing the fate of the majority of its inmate population?

“Just as we cannot incarcerate our way out of violence, we cannot reform our way out of mass incarceration without taking on the question of violence,” Sered writes in her book Until We Reckon: Violence, Mass Incarceration and a Road to Repair. “The context in which violence happens matters, as do the identities and experiences of those involved.”

Her approach argues that solutions must be centered on survivors’ needs. They also should be driven by accountability, with the perpetrator acknowledging harm and expressing remorse. Any resolution in a case should place public safety at its center and also be guided by racial equity.

There is increasing evidence that use of restorative justice lowers rates of recidivism.

Following Satana Deberry’s victory in 2018, her office began a book club and Until We Reckon became one of its first titles. The office significantly expanded its use of the practice as Montgomery-Blinn encouraged her colleagues to look for the so-called “green flags” that might make a case resolvable outside of traditional prosecution: were victims asking questions that were unlikely to be answered in a court setting? Had they experienced negative interactions with the criminal legal system in the past? Did an offender show early signs of remorse?

All could be signs that a case could be diverted from a traditional prosecution, where defendants are often encouraged to remain silent, leaving questions like “why did this happen?” rarely answered in full.

Last year, Restorative Justice Durham resolved 23 felony cases through the process, up from seven the year before.

Deberry, who was re-elected in 2022, is aware of the political pitfalls of such work, as violent crime remains a polarizing political issue. But she is direct in addressing them.

“We’re more worried about doing the wrong thing than we are about doing the right thing,” she said. “And if that makes me a target, you know, I’m a Black woman in America. I’m a target anyway.”

Annette Love met with members of the Fields family for the next six months, holding circles in the offices of a local church alongside an administrator from her organization and an independent attorney.

The group, which did not include Don Jr. at this point, would take turns talking uninterrupted, the speaker holding a small stone until they were finished. Alex spoke about the lingering loss he felt after the killing and thought deeply about the people and experiences that had shaped him.

The Fields family had experienced many traumas over the decades. Alex was born in the Jim Crow era and attended a segregated school in the rural suburbs of Durham, his family suffering the manifold indignities and injustices of legalized white supremacy. He had lost two of his brothers in youth: three-year-old Ronald from pneumonia and 29-year-old Dwight after a ruptured pancreas.

The loss of Ronald made Don Sr. the youngest of the eight siblings, and Alex, 12 years his senior, became a father figure in Don’s life. The two looked almost identical as well, both handsome with slim jawlines and deep dimples. In their youth, they were the best of friends.

All the Fields siblings had been raised with strict moral guidance from their parents to always respect each other— even in disagreement—and to forgive.

He thought about his own sermons. As a part-time minister, he would regularly preach forgiveness from the pulpit on Sundays: “How can I preach it, if I don’t forgive my nephew for what he’s done, but yet I want God to forgive me for everything that I’ve done wrong?” he said.

After circling for months, members of the family asked Love to pass the message to Don Jr.: they still loved him, they were willing to forgive. As part of their formal mediation offer, known as a repair agreement, the family wanted Don Jr. to receive regular therapy while he was held in jail.

Love, who speaks with the rhythmic intonation of a seasoned minister, met Don Jr. for the first time in early 2020.

He was quiet, she said. “He did not want to open up to us, and yet he agreed to the process,” Love recalled. “He wanted to do it for his family.”

But the minister, who has worked with victims of violent crime for a decade, observed a calmness at odds with the severity of his offense. “He needed the therapy, the forgiveness,” she said. “He needed a sense of love and assurance.”

Don Jr. agreed to the repair agreement and a date was set for a first meeting with his uncle, who acted as the family’s sole representative in the first sessions.

It was the meeting that brought Alex Fields to tears. “I have to forgive you. I want to forgive you. And I want you to forgive yourself,” he had said.

They agreed to meet each other once a month in an effort to restore the relationship. The next four meetings went much the same; the emotions were so high. But gradually, as the uncle and nephew grew more acclimatized to each other’s presence, they edged forward.

Don Jr. acknowledged the harm he had caused; he committed himself to therapy to address his anger.

Eventually their conversation came to the question of why? It was not something Don Jr was able to answer in much detail.

“He wasn’t ready to talk about it. I think it’s so painful for him to know, first, that he committed such a horrific crime,” Alex said. “And then secondly, that it’s still a person [his father] that you’re supposed to love.”

He agreed not to address the topic any further until his nephew felt ready, but accepted that the killing had happened in a moment of rage, that the answer to “why?” may be something impossible to fully articulate.

By this time, the pair had been meeting regularly for a year. They would joke with each other, share stories, and look forward to their next session.

Alex invited other members of the family, including his two sisters and his niece Brittany Barbee, to their next session. Barbee, 29, had grown up with Don Jr. and saw him more as a sibling than a cousin. She had lost her father to a lengthy period of incarceration when she was seven years old, experiencing first-hand the devastating consequences of separation by long-term imprisonment.

She had no questions for her cousin about the incident itself. All she wanted to know was how he was after five years in jail, still awaiting an outcome in his case.

“Do I wish things would have been different? Yes, of course,” Barbee said. “But nothing, no question I can ask can change the fact, unless we’re talking about bringing my uncle back from the dead.”

“How are you? And how can we move forward? Those are my only questions at this point.”

After a year of family circles, Love believed they had brought the process to a natural close. Members of the family were talking again, laughing together, even. And Don Jr. was still receiving regular therapy.

But what did all this mean for the judicial process? A murder charge and the prospect of a trial still loomed.

The family reconvened with the DA’s office.

“We’re going to think outside the box,” Montgomery-Blinn told the Fields family as they sat in the DA’s office in 2021. “Anything you think you know about the justice system already, I want you to ignore it and tell me what you want next.”

The conversation turned swiftly to the central question: did Don Jr. need to remain incarcerated any longer? The assembled family members were in agreement that he did not. They had seen enough change. And they wanted him to gradually transition back to home, back to family.

This raised, for the first time, the prospect that Don Jr. could actually avoid being sent away to prison altogether, despite the severity of the charges.

He had been held in jail for almost six years but had not been to trial or received a formal sentence. The decision to slow down the process had meant he stayed in the county’s custody rather than being sent away to a prison elsewhere in the state, which made it far easier to facilitate the dialogue.

The DA’s office forged a new plea deal, which offered Don Jr. the opportunity to plead guilty to voluntary manslaughter, which could see him sentenced to “time served.” The family worked on a new repair agreement, which was 13 points long and had conditions facilitating Don Jr.’s release.

He would not commit any new crime. He would continue to receive therapy. He would stay away from his grandmother’s home, and respect the boundaries of certain family members who still wanted him locked away. He would find a job and live in transitional housing.

If he did not fulfill the terms, he could receive a harsher sentence of up to 10 years. He would have nine months on the outside to prove he could uphold the conditions and transition back into the public.

The repair agreement was used as the basis of the plea deal. It was, according to five restorative justice experts and practitioners interviewed by the Guardian, the first time they had seen an agreement used this way in a homicide case.

On 16 June 2022 Don Jr. was released from custody. He was wearing an ankle monitor. The clock began to tick.

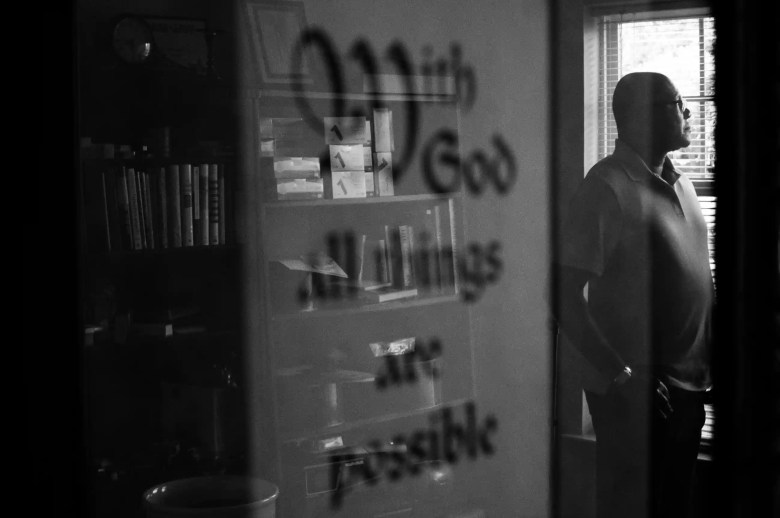

On Good Friday this year, Alex Fields stood in front of his congregation at the Faith Community Church International on the outskirts of Durham. Spotlights spun in unison and Alex preached with wild hand movements, bending his body in rhythm as the band crescendoed frantically. He drew from Luke chapter 23, verse 34: “Father forgive them; for they know not what they do.”

“Forgiveness is a powerful word,” he told the worshippers. “My family and I, we know what it is all about.”

He proceeded to tell the story of the killing.

“But the district attorney had a change of heart and says: ‘I believe he’s worth saving,’” he said. “I promise you, next Thursday he will be set free!”

Most in the congregation applauded, but a few seemed perplexed.

Earlier that day Don Jr. had stood on the porch of the transitional home as rain pounded the roof. He remained shy and retiring, declining to be interviewed in depth. It was just days before his final sentencing hearing, when a judge would determine whether he had met the conditions of his deal or would be sent to prison to serve more time.

“I try not to think about a lot of things,” he said. “Especially Thursday.”

The Fields case has become a transformational experience for the prosecutors involved, said Satana Deberry as she prepared for the hearing. While restorative practices in homicide remain rare, the instances of killings involving parties that have a pre-existing relationship is over 50 percent, according to FBI crime data.

Parricide accounts for about 2 percent of killings in the U.S., according to research, while in 2019 only 1,372 homicides occurred between strangers, equating to 19 percent of the 7,119 homicides where relationships were declared to the FBI.

The numbers, argues Deberry, mean that the process—despite the intensive resources it requires—can be replicated in other homicides and serious violent crime.

“It’s not so much stranger danger, as we like to say it is,” Deberry said. “Especially in cases of violence, people often have long-term connections with each other somehow, whether they are family members, or they are members of the same community, same neighborhood, young men who’ve grown up together, and ended up in these situations.”

It was a scorching spring afternoon when Donald Fields Jr. came to court with his uncle for the last time. They prayed together before the hearing, and Don Jr. pushed his uncle’s wheelchair as they entered the room.

Alex, a sharp dresser, wore a navy suit jacket. His nephew came dressed in a smart white polo shirt, wearing his thick glasses. The public benches were packed from the front to back, and included the police officer who had arrested Don Jr. in 2016, the facilitators of the restorative circles, the managers of the transitional home he had been living in, and members of the Fields family.

Deberry appeared wearing a necklace with the word “mercy” emblazoned in silver.

Montgomery-Blinn informed the court that Don Jr. had continued to meet all of the parameters of his deal. After months of searching, he had finally found a job—a cashier’s position at a local Burger King. It was the last condition of his plea that the court required.

She invited members of the community to speak before the judge.

First was Acie Bell, Don Jr.’s mother.

“When things happen to our children, they happen to us,” she said. “When they hurt, you hurt. When it’s the middle of the night and you don’t know what to do, you cry many tears. But sometimes things are not in our control. Life happens to us.”

“And I just want to thank you, all of you, for taking the chance. For helping him.”

Don Jr. watched and wiped a tear from his eye. His cousin Brittany was among the last to speak.

She paid tribute to her uncle Alex, for reaching out across a generational divide to save his nephew. “Thank you,” she said through tears. “The fact you wanted to do this for someone in my generation, in our family.”

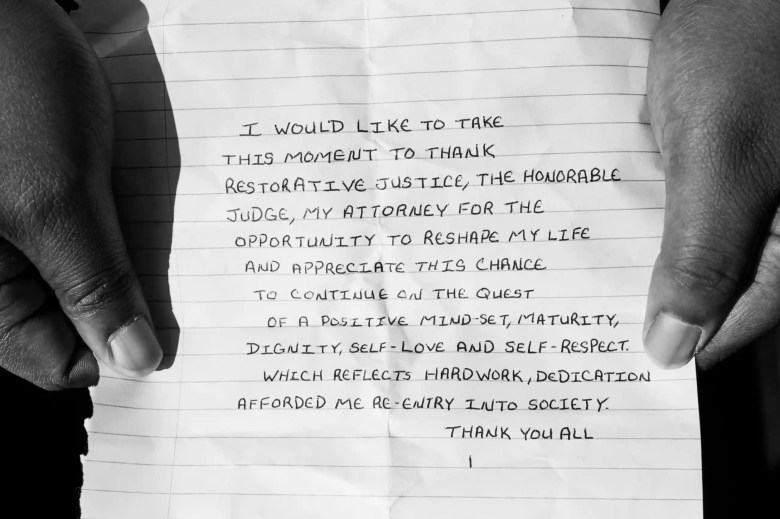

Don Jr. did not speak. But his lawyer read a brief statement to the court.

“I would like to take this moment to thank restorative justice, the honorable judge, my attorney for the opportunity to reshape my life and appreciate this chance to continue on the quest of a positive mindset, maturity, dignity, self-love, and self-respect,” it read.

As the proceedings wrapped, the judge sentenced Don Jr. to time served. He was free to leave. The courtroom erupted in a round of spontaneous applause. Cake was served by the judge’s bench.

Montgomery-Blinn, the prosecutor, and Don Jr., the defendant, shook hands.

As the process concluded, Montgomery-Blinn reflected on the other homicide cases she had tried in her career—10 of which had ended in sentences of life without parole.

“Every single one of those cases sits in my heart. And they should do for prosecutors,” she said. “But this case is in my heart in a really different way because I think we did something better.

“I hope this is the beginning. I hope this is the snowball rolling down the hill.”

Comment on this story at backtalk@indyweek.com.

Support independent local journalism.

Join the INDY Press Club to help us keep fearless watchdog reporting and essential arts and culture coverage viable in the Triangle.