Syracuse, NY — Black babies in Onondaga County are more than 4 times at risk of dying than white babies, the latest data shows.

The gulf between Black and white baby deaths is now twice as bad as it was a decade ago, an analysis by syracuse.com | The Post-Standard has found.

That’s primarily because, since 2011, white infant mortality here has nearly been cut in half. At the same time, the Black baby death rate has grown worse.

The racial gulf exists across the country: Black babies die at a rate about 2.3 times higher than white babies.

Here, that gap is twice as bad: Black babies die at a rate 4.6 times higher than white babies, the analysis found.

Recent improvements in medicine, prenatal care and safe-sleeping education have lowered overall death rates among babies less than 12 months old. Pregnancy complications, if detected early, are more often solved than in decades prior, health experts say.

But the deadly difference between races persists because it’s about more than medical access, health officials and experts say.

Some Black families are more likely to face hurdles that make childbirth risky, advocates and experts say. Lack of transportation and childcare make it hard to get to appointments. Stress from violent neighborhoods plays a factor in pregnancies, as do fewer healthy food options, those local experts say.

At the same time, racial biases in delivering health care to Black mothers also contributes to the higher rate of Black infant deaths, two local doctors said.

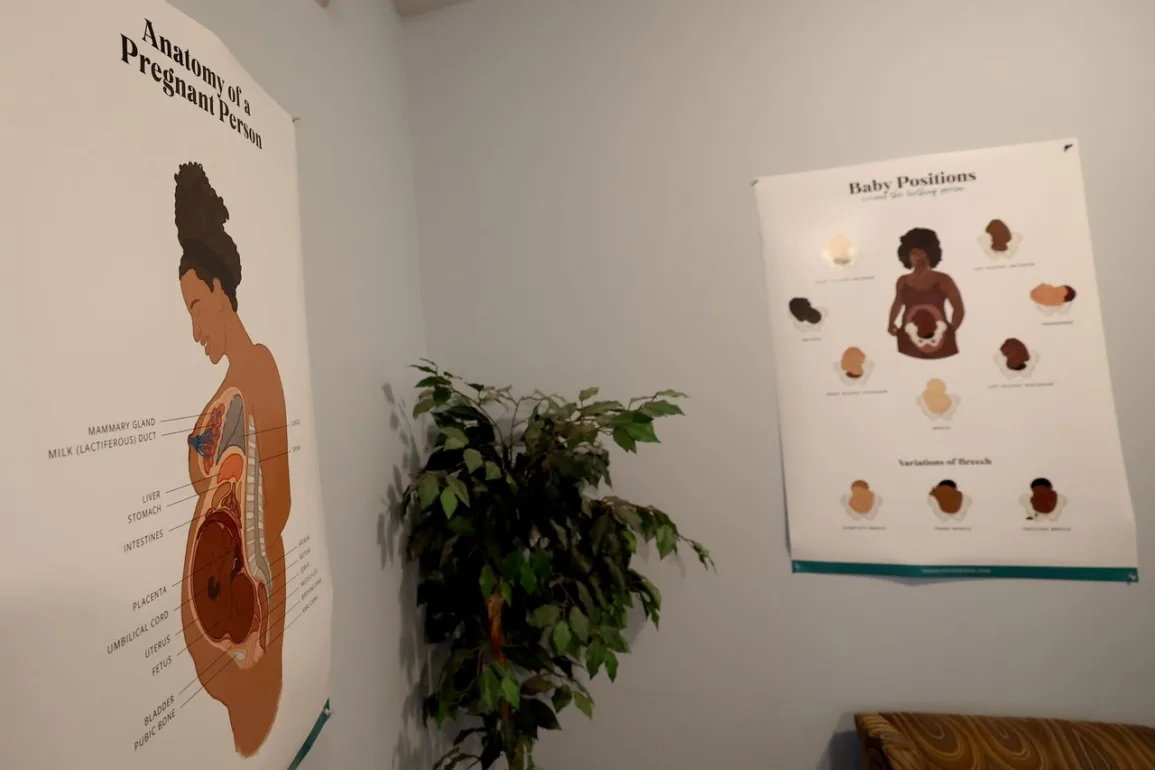

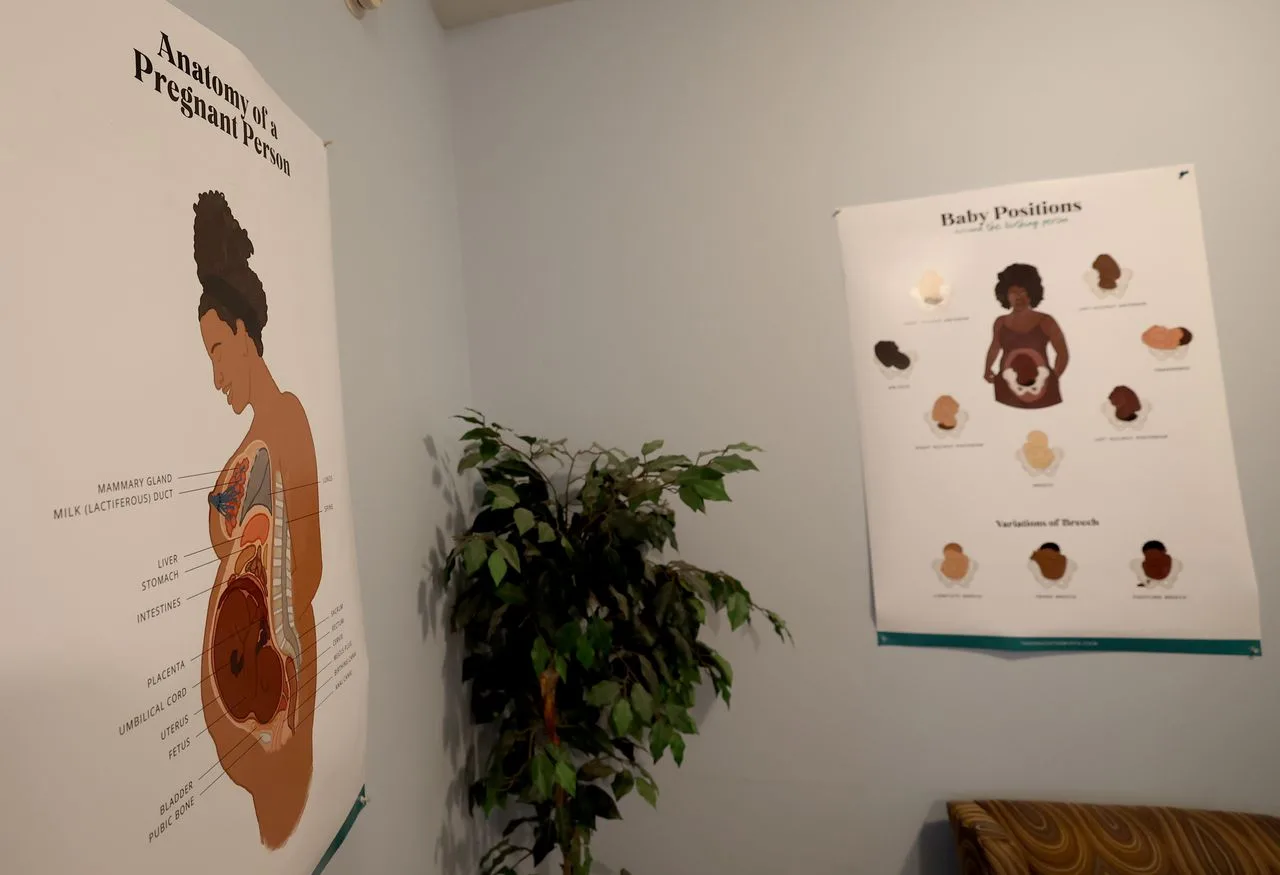

“It’s all about power,” said SeQuoia Kemp, a Black doula who seeks to reach pregnant women who feel cast aside by the system. She has joined forces with more than a half-dozen other Black doulas to open the Sankofa Reproductive Health and Healing Center, on South Salina Street.

There are simply too many Black pregnant women who are ignored or falling through the cracks, Kemp said.

This has led to higher rates of Black babies who are born too early and too frail to thrive on their own. A small percentage of those complicated births end in a baby’s death, often in neo-natal hospital departments.

Complications during pregnancy and premature birth accounted for 73% of baby deaths from 2017 to 2021, according to Onondaga County health department data. The other 27% of deaths were caused by sudden infant death syndrome, disease, sleep-related deaths and other causes.

The raw numbers also show how acute the problem is: 30 Black babies died in the county from 2018 to 2020, compared to 25 white babies in the same three years. That’s despite the fact the county delivers 3 times more white babies than Black babies.

The infant mortality gulf is more proof of how poverty and race have created disadvantages for babies from the very first breath, officials and community leaders said. Patients and families can be disillusioned and distrustful of health care providers after living through years of systematic racism.

Black women have reported feeling powerless or demeaned when seeking prenatal care. In a 2018 state-sponsored listening session, women described being convinced into care that they later regretted. One pregnant patient recalled going to an appointment, only to be told her husband wasn’t welcome because staff thought he might be a criminal. Another recalled going into labor at the hospital alone while staff threw a Christmas party outside her room.

“People have fear,” Kemp said, leading them to ask: “Why even go?”

Onondaga County isn’t alone when it comes to racial inequities in baby deaths across New York. In fact, Rochester’s home county has the worst Black infant mortality rate in the state, at 15.2 per 1,000 births from 2018 to 2020, according to state data.

The state infant mortality data for Onondaga County skews slightly higher than county numbers. That’s because some county residents die in other counties, which is not reflected in local data. But the story remains the same: Black babies die at a much higher rate.

Onondaga County’s Black death rate was 12.1 per 1,000 births from 2018 to 2020, according to state data.

Syracuse once had one of the worst infant mortality rates in the country. During the past three decades, a complex network of government and grassroots agencies have tackled the problem.

In Onondaga County, for example, six health department nurses do home visits for pregnant and post-partum moms, each helping 25 to 30 families at a time. There are more than a dozen other community health workers who strive to remove any barriers that might exist – from setting up pregnant women with bus rides to doctor appointments to arranging childcare while they’re gone – while also offering safe-sleeping education, baby formula and providing government-subsidized access to fresh foods.

The state funds one program, Healthy Families, while the feds fund another similar program, Syracuse Healthy Start. Each are run through the county, engage community partners, and aim at reducing infant mortality.

The county has two nurses who are fluent in Spanish and eight of the home visit workers are people of color. There’s also a network of non-profit groups, from Catholic Charities to area hospitals, who collaborate to reduce infant mortality under the Early Childhood Alliance.

Home visits, at the core of prevention efforts, were stopped during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, but have fully restarted, county officials said.

Sankofa Reproductive Health and Healing Center. The healing center at 2331 S. Salina St. provides pregnancy and reproductive care to Black women. It offers doula care, breastfeeding support, wellness counseling and advocacy. dnett@syracuse.co

These efforts have helped hundreds of moms each year who are looking for help. And it has had an impact: our overall infant mortality rate is better than the national average, even while our Black rate still lags.

None of the babies born under the Healthy Families home visiting program died from 2019 to 2021, records show.

There remains a steady flow of millions in federal, state and local money aimed at Syracuse’s high infant mortality – a product of the high rate of Black baby deaths. The inner-city federal program, Syracuse Healthy Start, started in 1991 and can continue getting funding until the city’s rate is below 2.5 times the national average.

But money alone hasn’t – and won’t – solve the problem from here, said Dr. Rob Silverman, who runs the regional perinatal system at Upstate University Medical Center..

“A lot of people have assumed if you throw money, we’ll fix it,” he said. “But it’s not just poverty. It’s implicit bias in healthcare. It’s people getting less-advantaged care.”

In a June 2023 report noting racial disparities in infant mortality, the state pointed out that people of color are less likely to receive routine medical procedures and experience a lower quality of care overall, even when controlling for insurance status, income, age and severity of conditions.

“I think we have to bring up the persistent racism and discrimination that we have seen that also drive these racial disparities,” said Dr. Marilyn Kacica, the medical director for the division of family health at the state Health Department, in a recent interview about the report.

That disparity in care has fueled Kemp’s mission as a Black doula to attract women who often feel abandoned or ignored by traditional healthcare providers. She gets referrals from both hospitals and word of mouth on the street.

Despite their reluctance, getting those women prenatal care and post-pregnancy care is important, Kemp said. That’s how problems during pregnancy are addressed, improving the chances of a successful birth.

In an example of government partnering with the community, Kemp is gearing up to be a mentor for other doulas through the Healthy Start program.

But no one knows how many women in Onondaga County are in desperate need for help during pregnancy and in postpartum. In other words, how many women aren’t reached by the dozens of health workers and myriad of government aid?

“We know there are a ton of people who are having kids who could use our services,” said Sunny Jones, Healthy Start’s program coordinator. “We want to get in contact with them.”

Staff writer Douglass Dowty can be reached at ddowty@syracuse.com or 315-470-6070.

Sunny Jones is program coordinator for Syracuse Healthy Start.