This story was originally published by NEXTpittsburgh, a news partner of PublicSource. NEXTpittsburgh features the people, projects and places advancing the region and the innovative and cool things happening here. Sign up to get their free newsletter.

As a Black business owner, James Carter says he faces issues that many non-minority entrepreneurs don’t encounter.

Among them: a lack of Black role models who are entrepreneurs.

“There was one business owner in my family when I was growing up,” says Carter, 52, who was raised in Youngstown, Ohio, and graduated from Thiel College in Greenville, Pa.

As studies show, Black entrepreneurs also have a tougher time obtaining capital to fund their businesses.

“You don’t have immediate resources,” says Carter, of Avalon, whose firm, C&J Financial Foundations, provides bookkeeping, payroll, cash management, business planning and other services. “So finding value and maintaining value in the business is a little challenging.”

Entrepreneurs Forever, a nonprofit with a mission to grow small businesses, is stepping up its efforts to assist more Black-owned firms like Carter’s.

The organization this year received a $250,000 grant from the Heinz Endowments to help boost the revenues of 36 Black-owned businesses that participate in its program.

“We want to rally around them and help them grow,” says A.J. Drexler, chief executive of Entrepreneurs Forever, which operates 29 peer learning groups in Pennsylvania, including 22 in Allegheny and other southwestern counties. It operates 20 cohorts in other states.

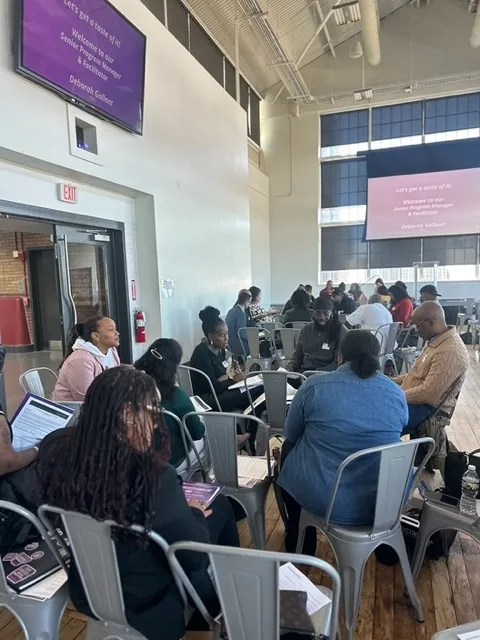

Each cohort includes 10 to 12 entrepreneurs from various business sectors who meet monthly to analyze specific challenges of running their enterprises. They are led by experienced business owners who facilitate discussions and provide hands-on exercises to help members work through issues. Since the Covid-19 pandemic, all groups have gathered virtually as well.

The Heinz grant will cover the costs for 36 Black entrepreneurs to participate for two years including facilitators, access to its digital platform and curriculum, and some monthly add-on sessions for participants to take “deep dives,” says Drexler. Those costs total $4,000 per year per participant, she says.

Entrepreneurs Forever does not charge fees to participants but seeks funding from foundations, government and individual donors to support its programs. It’s the signature initiative of the Mansmann Foundation, a charity founded by the late Joseph Calihan, a private investor whose grandparents owned Mansmann’s department store, a former East Liberty landmark.

Calihan credited his success to his experience in a peer-to-peer network for executives.

Last year, Entrepreneurs Forever received $1.2 million from the U.S. Small Business Administration to expand programming in Pennsylvania beyond the Pittsburgh region. In October, it held an information session at the Energy Innovation Center in the Hill District to sign on more business owners in Allegheny County with the SBA funding.

To be eligible, individuals must own a full-time business operating for at least one year with minimum sales of $30,000.

“I know it’s really hard to run your own business,” Drexler told audience members at that session.

She owned Campos, a marketing research and branding firm, until 2023 and previously co-owned an advertising agency.

Entrepreneurs Forever aims for 58% of its members to increase their company revenues during the first year they participate in the program and 90% in the third year.

The program also aims to help solo entrepreneurs generate enough revenues to hire additional employees.

“If you don’t become an employer business, the benefits of entrepreneurship don’t accrue for you,” says Drexler.

Carter founded his firm in 2007 as a side gig to help people file their annual tax returns.

He began growing it into a year-round bookkeeping business after he was laid off from his accounting job with a Downtown construction and design company.

In early 2020, he attended his first meeting of an Entrepreneurs Forever cohort based in Homestead.

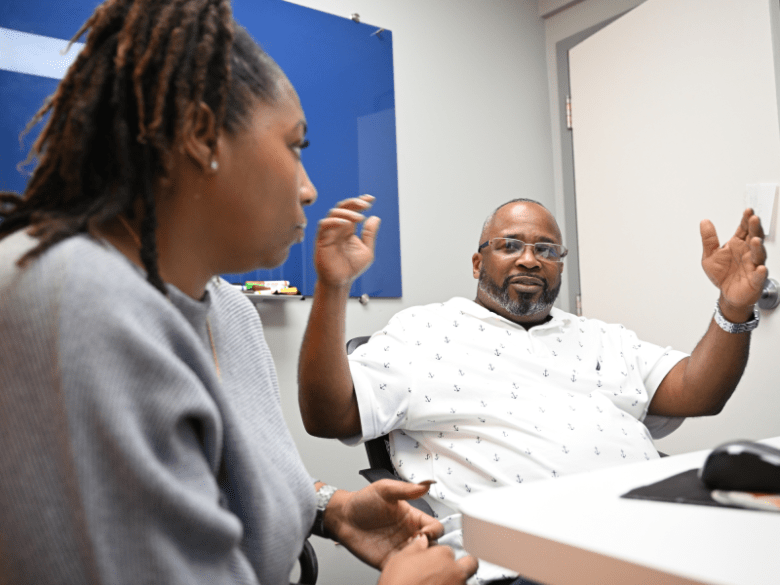

Carter quickly realized the group wasn’t a forum for traditional networking or a place to share sales leads.

The participants spoke frankly about day-to-day challenges — from messy personnel problems to marketing mistakes — then dug in to help each other craft solutions.

Since then, Carter says his peers in the cohort have become “trusted guides to each other.”

Danielle Wells, 40, a Black business owner based in Farrell, Mercer County, joined a cohort in March.

Her business, The Wright Agency, provides in-home care for elderly and disabled individuals.

“Being in the program has had a positive effect on me and the company,” says Wells. “It gives me a place to share the good and the bad of being a business owner in a supportive environment. I get really great tools to develop my business.”

She launched her firm in 2017 and has faced obstacles in getting financing that she attributes to racism.

While trying to sign up for a program for minority customers at one bank, Wells says an employee “kept withholding information and stringing me along.”

She eventually contacted the bank’s corporate office, received an apology, met with another employee — who was Black — and was enrolled.

“In banking, I feel that I have to work three times as hard to grow my business to scale,” she says.

Drexler says participants in Entrepreneurs Forever get “results from our model of motivation.”

“If you want to complain to the group, no. If you want to solve problems, yes.”

Joyce Gannon is a Pittsburgh-based freelance writer.