About 30 years before the Civil War, David Walker went viral.

The son of a free mother and an enslaved father, Walker wrote an antislavery pamphlet that spread throughout the South in the pockets of Black sailors and by word of mouth. Literate Black people read it to scores of those who could not.

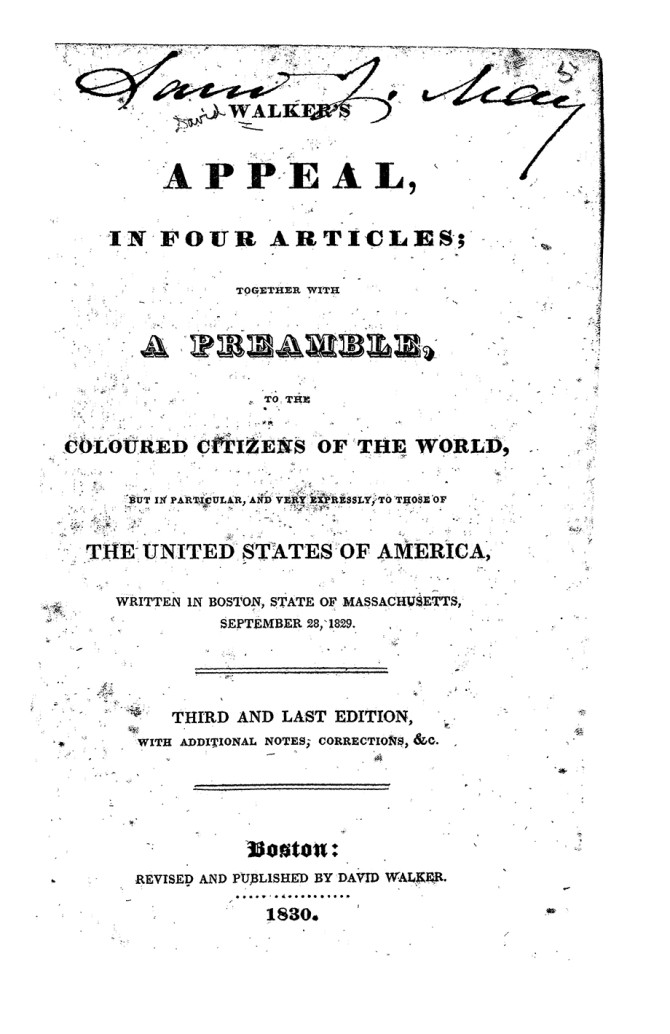

In three printings from 1829 to 1830, Walker’s incendiary “Appeal to the Colored People of the World” urged enslaved people to unite around an early form of Black pride and actively fight for their freedom. It became one of the most radical documents of the era.

In 1829, David Walker’s “Appeal to the Colored People of the World” urged enslaved people to unite around an early form of Black pride and actively fight for their freedom. It became one of the most radical documents of the era.

Caches of the pamphlet spread at least as far as Savannah, Georgia, by December 1829, and by early 1830 it had had made its way as far as New Orleans.

Walker’s “Appeal” enabled enslaved people to imagine freedom and why they deserved it, says Lenora Warren, assistant professor of literatures in English in the College of Arts and Sciences. “Words are one of our best ways to express the imaginary,” she said.

“So much of the process of enslaving people was trying to force them not to be able to imagine freedom. But it was literally impossible for the Slave Power to do that – it never succeeded in making people believe wholesale that they did not deserve to be free. Juneteenth is the culmination of that,” said Warren, a scholar of Early American and Early African American literature with a focus on literatures of abolition, insurrection and the politics of resistance.

The details of Walker’s early life are fuzzy, but it’s known that he was born in North Carolina around 1796, was free, and learned to read and write. He made his way north to Boston. There he became involved in the Massachusetts General Colored Association, which focused on increasing Black literacy and creating Black publications and reading rooms, and other organizations focused on antislavery views.

He started working for the Freedom’s Journal, the first Black-led publication in the country, based in New York. “And this is key, because he becomes one of their authorized agents, who sold subscriptions by going to cities and putting the newspaper in peoples’ hands,” Warren said. “And it’s believed this is how he started to circulate the ‘Appeal.’

“You have this wonderful confluence of this very potent document with the networks that the Freedom’s Journal had built to circulate the pamphlet,” she said.

Walker was writing at the time of the first Missouri Compromise, when Congress debated whether Missouri territory would be admitted to U.S. as a slave state, and when the African Colonization Society advocated for repatriating free Blacks to Africa. Walker was also responding to Thomas Jefferson’s “Notes on the State of Virginia,” in which Jefferson catalogues the supposed deficiencies of Black people and why they could never be citizens of America.

The “Appeal” is divided into four sections, Warren said, refuting racism, calling for equal rights, and urging the resistance of oppression with Black nationalism. “They say, ‘We are wretched because of our condition of slavery, we are wretched because of our ignorance.’ He’s building an argument of, ‘We’re not wretched because we are Black. We are wretched because of what has been done to us,'” Warren said. “It’s Black Pride before the 1970s Black Pride movements. It’s a document of him saying ‘They’re wrong, what they say about Black people.'”

The “Appeal” was especially controversial because of the militant language Walker used, including “kill or be killed.” He wrote:

“The whites have had us under them for more than three centuries, murdering, and treating us like brutes; and, as Mr. Jefferson wisely said, they have never found us out – they do not know, indeed, that there is an unconquerable disposition in the breasts of the blacks, which, when it is fully awakened and put in motion, will be subdued, only with the destruction of the animal existence.”

” … They want us for their slaves, and think nothing of murdering us … therefore, if there is an attempt made by us, kill or be killed … and believe this, that it is no more harm for you to kill a man who is trying to kill you, than it is for you to take a drink of water when thirsty.”

“That had not been done before, definitely not in the American context,” Warren said. “He seizes on the notion that African Americans have the right to revolt in pursuit of freedom, and uses Jefferson’s own words to underscore that point.

“He was viewed as a threat,” she said. “Some scholars see him as a precursor to figures like Marcus Garvey, for thinking of a kind of explicit militant Black nationalism.”

Of course, the colonists in the American colonies had done and thought the same thing during the Revolutionary, Warren said. “And he doesn’t incite insurrection. He just puts words to the insurrectionist feeling that already exists,” she said.

The message spread not only in print but also by word of mouth, as most Black people, both enslaved and freed, could not read. “People are reading it aloud so you have the potential for one pamphlet reaching multiple people,” Warren said. And it was reprinted over and over in other publications.

“It was very popular really fast,” Warren said. “But it was also scary to Southern authorities.”

They put prices on Walker’s head of around $10,000, equivalent to a six-figure number in 21st-century currency.

Black people in Charleston, South Carolina, and New Orleans were arrested for distributing the pamphlet and white Southerners’ fears about a Black rebellion came to fruition a few years later, during Nat Turner’s rebellion. That resulted in a backlash of laws restricting the movements of Blacks sailors and slaves and other laws against teaching slaves to read, write and gather in large groups.

“But that insurrectionist spirit doesn’t go away – it goes underground,” Warren said.

When she teaches Walker’s “Appeal,” it is one of the most popular texts of the period with students. “It never feels dated,” she says. “When they come into a class and they think, ‘What am I going to read from the 19th century that feels current?’ David Walker can feel really fresh for a lot of students.”