Dealignment Is Real. We Can Help Reverse It.

Matt Karp on how a political movement beating the drum for working-class populism can restore fraying ties between blue-collar workers and the Left.

Flags flown by supporters of Donald Trump are shown ahead of a rally featuring the former president at the Arnold Palmer Regional Airport in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, November 5, 2022. (Win McNamee / Getty Images)

American midterm elections are strange beasts. In a political system whose structures and symbols are rooted in executive and judicial power, purely legislative elections begin to feel like undercard events. A nationwide contest to decide which Congress will crank its engine while appointees, regulators, and judges actually make the laws? It hardly seems worth the time or expense.

And yet often in US history, a national midterm — not a single event but thousands of simultaneous and interlinked struggles — can mark a more distinct watershed than the clamor and color of a presidential election.

The Civil War, we know, was triggered by the victory of Abraham Lincoln and the Republicans in 1860. But the revolutionary crisis we call “the American Civil War era” really began with one midterm (1854), when a new antislavery party swept the North, and ended with another (1874), when the last live embers of Reconstruction were stamped out by Southern violence and Northern retrenchment.

More recently, the right-wing landslide in the 1994 midterms — which effectively created the red and blue maps we use today — did more to define its political moment than either of the Clinton-Perot presidential campaigns.

In the same way, it may be that the 2022 midterms — uneven and disjointed as they were — offer a better window into our own terrain than any of the Obama or Trump elections of the last two decades.

That landscape, familiar enough to anyone paying attention, is dominated by two central features. First, an intensifying polarization between the two major parties, expressed in high turnout, apocalyptic rhetoric on all sides, and partisan labels that communicate not just voter allegiance (“Republican” or “Democrat”) but social milieu, cultural value system, and moral habitus (“red” or “blue”).

Second, the gradual, uneven, and yet largely unabated march of class dealignment, in which downscale voters — with less education and lower incomes — move toward the Republicans, while upscale voters make a parallel and opposing journey toward the Democrats.

The 2022 midterms did not make this political order. But they do offer a convincing map of its topography. And they provide some telling hints about how the slow advance of dealignment might be beaten back.

Red Ripple

Before the elections, conventional wisdom favored a Republican rout. In recent history, new incumbent presidents — especially after replacing an opposing regime — tend to face a wave of annihilation in the midterms. The legislative agendas of Reagan, Clinton, Obama, and Trump were devoured in 1982, 1994, 2010, and 2018. The only exception came in 2002, when the aura of September 11 provided an unusual sanctuary for George W. Bush.

The emergent psychologies of Team Red — aggressive, careless, inclined to overcompensation — and Team Blue — besieged, fretful, lacking a proper estimate of its own strength — led both sides to forecast a GOP stampede. A range of misleading partisan polls, themselves not unrelated to this emotional divergence, only exaggerated those expectations.

In this climate the November results, though a plain reflection of the national stalemate — one party holding the Senate, while the other took the House — felt like a naked win for the Democrats. Party operatives did not stint in their exaltations: “Democrats were able to defy history this election,” declared Simon Rosenberg, one of the few partisan pundits who had confidently predicted a Republican fizzle:

The Democratic Party feels very strong right now. We’ve had 3 impressive elections in a row. Our candidates are now consistently outraising Republicans, sometimes by 3–4–5 to 1. Our superior field operations help drive a decisive early vote. . . . Our top 20–40 leaders are as strong as any point in my time in politics. We passed an agenda which will be making things better for Americans, helping us win the future, for decades.

In truth, 2022 was a very limited Democratic triumph. Blessed with a favorable map of Senate contests, and boosted by the Supreme Court’s hugely unpopular assault on abortion rights, Democrats managed little more than a defense of their existing encampments. John Fetterman’s victory in Pennsylvania must be weighed against defeats in Wisconsin, North Carolina, and everywhere else the party tried to break new ground statewide.

Though Republicans only gained nine seats in Congress, they won nearly 51 percent of the congressional popular vote, the party’s third-best result in the twelve elections this century. That figure was padded by the growing number of deep-red districts in which Republicans ran unopposed — and yet even this trend itself underlines the weakness, indeed the utter disappearance, of the Democratic Party outside its metropolitan strongholds.

After many cycles of frustration and neglect, the contested 2020 election appeared to convince Democratic leadership of the tactical significance of state legislatures. In 2022 Democrats made an unprecedented investment in state house races, and in many ways it paid off: this was the first election cycle since 1934 in which the incumbent party did not lose a single state chamber. Against expectations, Democrats actually won back the Pennsylvania House, the Minnesota Senate, and both chambers in Michigan.

Nevertheless, Republicans won more legislative seats in 2022 than they did in 2020, and still control over seven hundred more total seats than their rivals. At best, Democrats have only made a modest dent in the enormous state-house deficit they accrued in the Obama-Trump years. They did not lose a single chamber last fall, it might be said, because they scarcely controlled a competitive chamber in the first place. Between the coasts, Republicans remain the dominant party of state government in the United States.

Geographic Bunkers

The true story of 2022 was not Democratic triumph, but deadlock, entrenchment, and geographic consolidation. It is no coincidence that its major political fruit, for the first half of 2023, was a predictable and pointless partisan wrangle over the debt ceiling.

In many ways the November midterm election was not one election at all, but several different elections held on the same day. In Florida and New York, Republicans won a classic wave victory almost on the scale of 1994 or 2010. In Pennsylvania and Michigan, meanwhile, it was much more like 2002, with incumbent Democrats bucking history to gain ground in statewide, congressional, and legislative elections.

Other swing state results were more ambivalent: Democrats squeezed out what could be called defensive victories in Georgia, Arizona, and Nevada, but did little more than avoid obliteration in Wisconsin and North Carolina.

Almost everywhere else, the results told the same tale: a further acceleration of the existing partisan divides, as the red districts on the map grew more and more crimson, while the blues became an even richer shade of azure.

Across the upland South — West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas — already-dominant Republican parties gained thirty-three further state-house seats; in the mountain West, outside Colorado and Nevada, they gained another fifteen. Republicans won big in the swing states of the past, Ohio and Iowa, and extended their majorities in the purported swing states of the future, Texas and South Carolina. Somehow they even squeezed another five seats out of North Dakota, where (as in several other scarlet states) they now command nearly 90 percent of the legislature.

In blue America, it was the same story in reverse. New York saw an exceptional defeat, managed by a disastrously weak state party; California and Oregon too yielded disappointing harvests. But elsewhere, the blues got bluer. Democrats managed to flip thirty-six state-house seats in New England, a result aided but not wholly explained by the swing in New Hampshire’s oversized assembly: they also made gains in Massachusetts, Vermont, and Connecticut.

In Washington, Democrats cemented their control of the legislature; in Illinois they netted two congressional seats and five more in the state assembly; in Maryland, they took another five in the legislature; and in Colorado, now deeper blue than the Pacific Northwest, they added seven.

These consolidations bore the stamp of legislative redistricting, as both parties used the 2020 Census to lock down their prevailing advantages. Outside a dozen or so fetishized “battleground” states, American politics is a two-party system marked by one-party rule in the provinces. Over three-quarters of the US population lives in a state where the opposition party exists as little more than a token minority.

This structure has been engineered from above, but it both reflects and accelerates geographical polarization below. Rural counties from Central Florida to Eastern Washington, 60 or 65 percent Republican a decade ago, now routinely give 75, 80, or 85 percent of their vote to the GOP. Longtime liberal bastions, like Montgomery County, Maryland, or Boulder County, Colorado, were likewise 60 percent Democratic in the Bush era, 70 percent in the Obama era, and are 80 percent blue today.

If 2022 was a “stay the course election,” as Rosenberg and other pundits agree, the course points not toward Democratic hegemony but extended impasse — with both parties growing rich and fat inside their geographic bunkers, while increasingly unable to compete outside of them.

Dealignment Digs In

For both parties, these geographic frontiers are hard to separate from equally intransigent demographic limits. Republicans continue to struggle in most large metropolitan areas, chiefly due to their ever-declining support among well-educated, relatively well-off voters. Democrats, meanwhile, continue to lose ground with large swathes of the working class. Even in an election cycle where the party outperformed history and expectations, less-educated voters did not rally to the Democratic banner.

As observers like Ruy Teixiera, Timothy Noah, and David Sirota have all noted, Democrats fared worse with non-college-educated voters in 2022 than in either of the last two elections. Among white voters without a four-year degree, according to the AP-NORC VoteCast survey, the party’s deficit has now grown to a punishing minus-thirty-five points.

And by now, we know that the Democrats’ recent struggles go much further than the so-called white working class. Since 2012, according to the progressive data firm Catalist, the party’s support has waned significantly within every single subgroup of voters without college degrees. Among the “black working class,” congressional Democratic margins have dropped by eleven points; among the “Latino working class,” the margins have sank by twelve; and for the “Asian working class,” the number is eight points.

This slump can be easy to miss, because the Democrats’ overall support from these groups remains high. But across the last decade, the trends are notable. While Democrats have actually made gains with college-educated voters of color, according to Catalist, less educated African Americans, Latinos, and Asians (along with “Others”) have swung toward the Republican Party.

The general decline includes almost every group, and by some measures, as Teixiera points out, it is more dramatic than any movement within the “white working class.” It seems to be non-white, non-college-educated men that Democrats are losing at the fastest clip. In 2012, Catalist reported, that group gave Democrats a fifty-three-point advantage in congressional elections. In 2022, according to VoteCast, the same margin was down just twenty-three points. This thirty-point swing may be the most striking demographic shift of the decade — the piston turning the crankshaft of American class dealignment.

And even when Democrats win elections, their coalition looks rather different than it did ten years ago. A closer look at two states in which Democrats performed well in 2022 — Minnesota and Michigan, where they flipped state-house chambers — only underlines the party’s ongoing transformation.

The geography of dealignment was most vivid in Minnesota. In the blue-collar Iron Range, historically one of the most loyal Democratic regions in the country, the party got mauled, losing five legislative seats to Republicans. Defeated representatives included Rob Ecklund, who worked in a paper mill for thirty years before entering politics, and Mary Murphy, a social studies teacher who had served in the state house since 1977. Even these long-tenured and working-class legislators, the most resilient Democrats in the region, were not safe from the national trend.

Yet even as the mining towns north of Duluth slipped out of their grasp, Democrats grew their margins in affluent Twin Cities suburbs like Edina (annual household income: $115,000) Eden Prairie ($120,000), Lake Elmo ($160,000), Orono ($160,000), and North Oaks ($221,000). These and other metropolitan victories, partly aided by a new district map, were enough for the party to overcome its Iron Range defeat and flip the state senate from red to blue.

New maps offered Democrats a boost in Michigan, too, successfully breaking down an aggressive Republican gerrymander in both chambers of the legislature. Meanwhile, incumbent governor Gretchen Whitmer cruised to reelection. Boosted by a popular ballot measure to guarantee abortion rights, Whitmer ran ahead of Joe Biden, beating her own 2018 benchmark across the state. She trimmed Republican margins in much of the rural north, while slowing the tide of Democratic retreat in some working-class towns like Muskegon and Mount Pleasant. And in many of the more educated communities along the shores of Lake Michigan, from the Indiana border all the way up to Traverse City, she claimed new territory, often running ahead of Barack Obama in 2012.

Yet on the whole the election told the same old story. Whitmer’s largest gains came in Michigan’s most prosperous metropolitan counties: Oakland, containing Detroit’s toniest suburbs; liberal Washtenaw, home to Ann Arbor; Kent, around thriving Grand Rapids; and Livingston, Michigan’s single wealthiest county, where Detroit’s traditionally Republican exurbs have trended blue across the decade. In these places — as in much of the United States — an easy rule of thumb applies: the more educated and affluent the precinct, the more pronounced the Democratic swing. In Oakland County as a whole, for instance, Whitmer’s margins grew by six points. But in Birmingham City ($137,000), Whitmer turned a thirteen-point win in 2018 to a twenty-five-point rout last year.

By contrast, the places where Whitmer lost ground nearly all fall below the state median in education levels, household income, and home price. Across most of the Upper Peninsula, as in Minnesota’s neighboring Iron Range, former Democratic strongholds received another coat of red paint: in Gogebic County ($42,000), a narrow Whitmer edge in 2018 became an eight-point shortfall last year. In places like Mecosta County in central Michigan ($48,000), or Tuscola County on the thumb ($55,000), where Obama trailed Mitt Romney by about ten points in 2012, Whitmer’s deficit ballooned to over twenty or twenty-five points.

These are rural and largely if not overwhelmingly white districts. But evidence of dealignment was available elsewhere, too: in the small, plurality-Hispanic town of Bangor ($46,000), in southwestern Van Buren County, Whitmer’s margin declined twelve points since 2018. More generally, throughout Michigan’s twentieth-century industrial core, sagging Democratic turnout and Republican defections dropped the governor’s margins. Whitmer netted fewer votes from working-class African Americans in Detroit and Flint than in her first campaign, while Republicans closed the gap in Saginaw and Bay counties. In Bridgeport charter township ($44,000), for instance, a diverse, working-class area outside Saginaw, her advantage shrank by over five points.

For perspective, this may have been Michigan Democrats’ most successful cycle in decades. It produced a gubernatorial reelection, majorities in Congress and the state legislature, and a landslide ballot victory for reproductive rights.

Yet in victory as well as in defeat, the Democratic playbook seems clear: in well-educated, relatively prosperous communities, usually suburban, the party aims to run up the score. In downscale areas, on the other hand, Democrats can do little better than slow the pace of retreat.

The Promise of Populism

Many Democrats, of course, see no problem with this new alignment: some national leaders, from Chuck Schumer to Hillary Clinton, can claim it as their own conscious handiwork. But others recognize that any attempt to fulfill the party’s own stated commitments — on issues from universal health care to the right to organize labor unions — requires winning a far larger share of working-class voters.

The current Democratic strategy has proven effective, in 2020 and 2022, at staving off the worst of the right wing. But it is not a recipe for governance. What does it say about a political party when it records a historic election “victory” and still loses control of Congress?

In their current incarnation the Democrats are very far from a party that can actually govern — that is, a party capable of winning majorities that can deliver meaningful national reforms. Voters without college degrees and household incomes under $100,000, after all, make up the vast majority of the electorate. Democrats, even in very good electoral cycles, are simply not winning enough of them. And when they have to face voters without the assistance of a popular abortion referendum, Democrats seem likely to get pummeled.

The electoral left, insofar as it can be distinguished from Democrats at all, shares the same dilemma. There is no path to an effective redistributionist coalition that does not go through a robust working-class majority. The rightward trend of less-educated voters in struggling communities — from Saginaw to South Texas — is a problem for socialists, too.

Given the persistence of class dealignment across the last decade, it is reasonable to ask: can individual politicians or campaigns do anything to change this pattern? In 2021, the Center for Working-Class Politics (CWCP) and Jacobin released a report suggesting that the answer is yes.

Surveying over two thousand Americans without college degrees, the CWCP found that these voters strongly prefer candidates who hail from working-class backgrounds, focus on bread-and-butter issues (especially jobs), and espouse economic populist (but not activist-flavored) rhetoric.

This spring, a second major CWCP report examined which kinds of economic policies and populist messages resonate most with working-class voters. This new study, which explored “class” by detailed occupational category, rather than education or income, has deepened and enriched the findings in the first report.

The results this time around were particularly striking among manual and lower-skilled service workers. Even when tested against a range of Republican messages, working-class voters lean toward non-elite candidates who address primarily economic priorities in class-conscious language. Again, universal rather than highly targeted or activist-derived rhetoric wins the most support.

Strikingly, the report found that many of these class-based preferences extend across lines of race or ethnicity. Working-class white voters strongly favor non-elite candidates, while upper- and middle-class whites do not. Similarly, black working-class voters strongly favor economic populist rhetoric, while black managers and professionals do not. Support for an aggressive, social democratic jobs policy, meanwhile — a federal guarantee for a stable job at a living wage — won huge support from working-class voters of all races.

As Jared Abbott, executive director of the CWCP, has argued in Jacobin, these findings illuminate the potential of a coherent left populist politics in America. The CWCP results suggest that despite the larger trends that have driven dealignment at the polls, individual campaigns may successfully win over working-class voters — including groups who gave majorities to Trump in 2020.

The 2022 midterms offered a chance to assess a few varieties of this approach in the real world. In a heavily Hispanic congressional district outside Chicago, Delia Ramirez built her campaign around an unapologetic, perhaps old-fashioned form of class politics. That meant, as Politico reported, “telling working-class Latinos the party is going to fight for them against the ‘rigged’ economic system that favors, as she puts it, ‘a bunch of riquillos,’ or rich people.”

For Ramirez, the key to winning Latino votes was “a straightforward economically progressive message — not threats to democracy or rhetoric on social justice issues but pocketbook issues such as health care and housing.” Last fall, she won her district by thirty-one points, beating projections by double digits, and running ahead of popular Illinois governor J. B. Pritzker in some key working-class neighborhoods.

In more competitive districts, a range of congressional newcomers like Marie Glusenkamp Perez and Chris Deluzio, along with veteran incumbents like Marcy Kaptur and Matt Cartwright, embraced elements of a progressive populist strategy.

Glusenkamp Perez, a former Bernie Sanders voter who owns an auto repair shop, put jobs and working-class identity at the center of her campaign in southern Washington. Cartwright, a member of the Congressional Progressive Caucus and a sponsor of Medicare for All, has built his reputation on protecting local workers and fighting unfair trade deals. His victory in November, in a Scranton-area district that national Democrats haven’t won in years, showed once again that a left populist message can win in Trump country.

Most prominently, Democratic challengers for Senate in Pennsylvania and Ohio mounted campaigns that resembled varieties of the CWCP model. It would be a stretch to call either John Fetterman or Tim Ryan a “left” populist, though Fetterman was an early Sanders ally, and few national Democrats have had stronger ties to organized labor than Ryan.

Despite the differences between them, there was a reason why many analysts — from Jennifer Rubin to the New Left Review — have grouped Fetterman and Ryan together as economic populists. Both put heavy emphasis on their non-elite backgrounds, attacked the Washington establishment, and aggressively pursued rural and working-class voters, campaigning in all sixty-seven counties in Pennsylvania and all eighty-eight in Ohio.

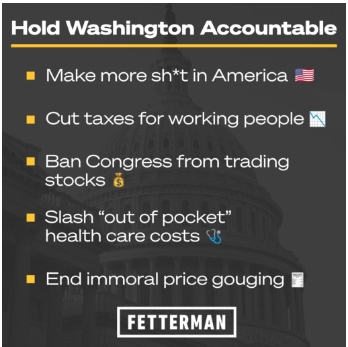

Fetterman’s blunt five-point agenda to “Hold Washington Accountable,” at the center of his messaging all year long, featured none of the national Democrats’ key talking points (regarding Republican extremism, election integrity, and abortion rights). Instead, it was economic populism all the way down:

Ryan, too, organized his campaign around jobs and trade deals, with an intensity of focus seldom matched by contemporary Democrats.

Though Fetterman and Ryan rejected certain activist rhetoric, neither retreated in substance from mainstream Democratic positions on immigration, policing, or LGBTQ rights. Confronted with right-wing attacks on these points, both tended to reject the culture war and attempt to bring the conversation back to economics, where they could denounce Republicans as tools of wealthy special interests.

In November, Fetterman won convincingly in Pennsylvania, while Ryan’s campaign ran aground in Ohio. Yet in many ways, Ryan’s defeat was as impressive as Fetterman’s victory. With Pennsylvania now established as the most valuable battleground in the country — essential to any would-be Democratic president — the party invested heavily in the state, making both the Senate and gubernatorial races the most expensive in national history. The Democratic Senate Majority PAC donated $42 million to Fetterman alone; altogether, Democrats (including outside groups) spent well over $200 million in Pennsylvania.

Fetterman was also fortunate in his opponents: not only the tone-deaf TV doctor Mehmet Oz, but the election-denying extremist Doug Mastriano, Republican nominee for governor, whose presence in the race repelled swing voters and juiced the Democratic base. In some ways, Fetterman ran on the coattails of Josh Shapiro, who won a fifteen-point landslide in the governor’s race.

Ryan had no such advantages. Since 2012, Ohio has become something like a Republican bulwark: in the last decade, the only Democrat to win a statewide election was incumbent senator Sherrod Brown in the very blue year of 2018. Though Ryan raked in small-donor contributions and remained competitive in polls, the Democratic Senate Majority PAC declined to invest in his race — even after his opponent, the memoirist-turned-MAGA intellectual J. D. Vance, received $28 million from Mitch McConnell’s Senate Leadership Fund.

More than most Democrats, Ryan actively sought to distance himself from the national party. This surely did not help his case with the Senate Majority PAC, but it is a move that the CWCP findings suggest is particularly effective with blue-collar and working-class voters — a group that recognizes that the infinity war of red and blue does not serve its interests. It’s no coincidence that Vance’s chief line of attack did not target Ryan’s populist economic plans, but his supposedly “100 percent” voting record with Biden, Nancy Pelosi, and national Democrats.

With nearly 47 percent of the vote, Ryan posted the second best mark (after Brown) of any Ohio Democratic candidate for senator, governor, or president in the last ten years. His fellow statewide candidates in 2022 — for governor, attorney general, secretary of state, and state auditor — all lost by somewhere between seventeen and twenty-five points. Ryan lost by just six.

Any contrast between the Pennsylvania and Ohio races, however, should not disguise the broader parallels between them. As Krystal Ball has written, Fetterman and Ryan both showed that a populist message can make a real difference in key swing states.

Unlike all but a handful of Democratic Senate candidates, all incumbents, both Fetterman and Ryan ran ahead of Biden in 2022. Both, too, did particularly well with working-class voters. While other successful Democrats (like Mark Kelly in Arizona or Maggie Hassan in New Hampshire) ran up the score with well-educated white voters, Fetterman and Ryan gained most among whites without a college degree.

All this was visible on the map. In Pennsylvania, Fetterman essentially held serve in the prosperous Philadelphia white-collar counties, equaling Biden’s benchmarks there. But all over rural Pennsylvania, his margins were significantly better: in southwestern Fayette County ($48,000), he improved by eleven points; in northeastern Carbon County ($57,000), he gained nine; in Erie County in the far northwest ($57,000), he gained eight.

In the evocatively named borough of Industry, Pennsylvania ($58,000), near the Ohio border, Trump beat Clinton by twenty-six points in 2016 — part of a historic landslide victory across once-Democratic Beaver County. In 2018, incumbent Democrats made a partial recovery, but Trump again crushed Biden, this time by twenty-eight points. This year, though, Fetterman cut the deficit to thirteen points — a fifteen-point gain on the president.

The old coal-country town of Nanticoke ($50,000), outside Wilkes-Barre in Matt Cartwright’s congressional district, is a classic “Obama-Trump” turf, giving 60 percent of its vote to Democrats in 2012, but falling to Republicans in 2016 by a double-digit margin. Biden closed the gap, but still lost by six points. Fetterman managed to flip it all the way back, winning Nanticoke outright.

In Ohio, Ryan did little better than match Biden in Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Columbus, along with their educated blue suburbs. But in the industrial areas along Lake Erie, he made larger strides, besting the president by five points in Sandusky County ($56,000), Lorain County ($62,000), and Ashtabula County ($47,000). In the rural southern half of the state, Ryan ran even further ahead: nine points in both Belmont County on the West Virginia border ($51,000) and Adams County on the Kentucky border ($44,000).

By definition these were marginal gains: a limited swing of votes, often in areas where the absolute total remained heavily Republican. It’s true, as Justin Vassallo notes, that neither Fetterman nor Ryan transformed the political geography of their states, which remain essentially divided between blue cities and red countryside.

Yet this too is in line with the CWCP’s findings, which point to marginal rather than wholesale benefits in an economic populist approach. The premise is not that campaign strategy in one race — candidate backgrounds, priorities, and rhetoric — can blot out a historical process whose roots reach back for decades, and whose momentum has accelerated in virtually every national election since 2012.

What the midterms do suggest, however, is no less powerful. In the time of Obama and Trump, no American political figure, movement, or idea has more convincingly embodied the course of History than the ever-rising tide of class-and-party dealignment. The world spirit on horseback, in the 2020s, is Wolf Blitzer pointing excitedly at a red-and-blue map.

To reverse that apparently invincible trend — even among a few hundred voters in an obscure, working-class place like Industry, Pennsylvania — is no mean feat.

The populist playbook is no magic formula for victory in every race. In Wisconsin, Mandela Barnes offered another version of progressive populism, running well statewide but falling just short — especially among working-class black voters in Milwaukee.

Nor is economic populism the only way for Democrats to win statewide: Whitmer in Michigan, Kelly in Arizona, and Raphael Warnock in Georgia all emphasized bread-and-butter issues, in their own ways, but it would be a stretch to call them populists.

Yet among statewide Democratic candidates, only Fetterman and Ryan made their most significant gains with the working-class voters the party needs — the voters necessary to create a robust majority capable of sustaining a redistributive agenda.

Since the midterms, Biden himself seems to have digested this insight. His State of the Union, which called for a “blue-collar blueprint to rebuild America,” signaled a conscious effort to fight for working-class voters in terms similar to Fetterman and Ryan.

Whether the whole of the Democratic Party is on board with this program, however, remains doubtful. The generation of leaders waiting behind Biden — including Kamala Harris, Pete Buttigieg, and Gavin Newsom — have shown little inclination to move beyond red versus blue, and even less interest in economic populism.

In Congress, when swing-district Democrats met to pick a “battleground representative” in the party’s leadership caucus, they chose Abigail Spanberger, from the affluent and highly educated Northern Virginia suburbs, over Pennsylvania populist Matt Cartwright.

Even in the Midwest, populism has struggled to keep a foothold. Elissa Slotkin, the former CIA agent elected to Congress in one of Michigan’s wealthiest districts, recently announced her candidacy for Senate in 2024, to replace the retiring Debbie Stabenow. She has already been embraced as the “consensus candidate” by Democratic power brokers. Even in the old Rust Belt, Slotkin seems more likely to embody the party’s future than Fetterman or Ryan.

But for any left-wing political movement that aims to change the United States, rather than simply administer it in comfort, the 2022 midterms offer an unusual ray of light. Of course, populist campaigns are no panacea. The chief hope for any transformation in the American economy lives — as always — with workers themselves, in the labor movement.

But electoral politics are a key front in this struggle. And, for the first time since 2016, it seems we may have a battle-tested weapon in the fight against dealignment. With a political movement beating the drum for working-class populism in every election cycle — with a thousand Cartwrights and Ramirezes, from Industry, Pennsylvania, to the Pacific coast — it is just possible to imagine making a real difference.