Factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine confidence and access among youth experiencing homelessness

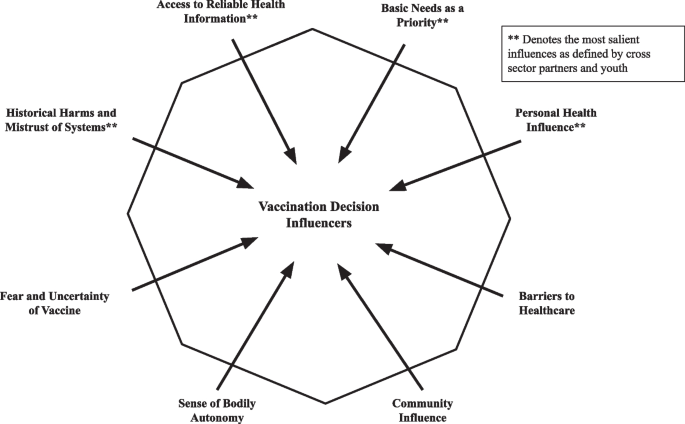

Our analysis revealed eight factors that influenced COVID-19 vaccine confidence and access among YEH: 1. historical harms and mistrust of systems, 2. access to reliable health information, 3. basic needs as youth’s priority, 4. personal health influence, 5. barriers to healthcare, 6. fear and uncertainty of the vaccines, 7. sense of bodily autonomy, and 8. community influence. The former four factors were identified as most salient by youth and cross-sector partners. Figure 1 illustrates these eight themes and how they may influence YEH’s decisions to receive the COVID-19 vaccine.

Vaccination Decision Influencers Identified by YEH and YEH-Serving Staff. Eight key themes were identified by youth and YEH-serving staff as factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine confidence and uptake among youth experiencing homelessness (YEH). Factors denoted with an asterisk were agreed upon by cross-sector partners and youth as being most salient for youth

Historical harms and mistrust of systems

Both YEH and agency staff articulated the influence of historical harms and the experience of marginalization and systemic oppression on their confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine. Mistrust of systems was particularly salient and emerged as an influence that likely impacted several of the other factors. Though we initially coded “historical harms” and “mistrust of systems” separately, the two codes were found to be intersecting and inter-related, and, based on input from our cross-sector community partners during the reduction process, we merged and re-coded as a single code. In interviews and focus groups, historical harms and marginalization by systems were demonstrated through elements of mistrust and uncertainty of healthcare delivery among youth, both within and outside of the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Both youth and staff frequently commented on the heavy impact that mistrust of the healthcare system had on their perceptions of the COVID-19 vaccine, resulting in rightful hesitancy to interact with healthcare, particularly as a person of color. For instance, one youth said, “They’re lying. You know, some people think it’s a population control attempt. You know, racist. Like, some certain drugs were made by the government to get rid of Black people. It happened.”

Staff, who spend a lot of time conversing with youth at their agencies note that the government’s role in vaccine communication is complex. A staff member indicated government mistrust as a multi-faceted influence for youth, describing, “There’s definitely distrust because it’s a systematically racist government, but I think also, they don’t trust it because it’s a government and they don’t have that rapport with it. So, I think it’s a combination of a two-sided coin and it’s on both sides.” Some staff members commented on the importance of recognizing healthcare’s historical harms in the context of vaccine discussions: “Even in the medical field, there’s been very unethical things that have happened in the past, and just acknowledging that and apologizing for that, but saying this is really important for our safety. And this is what it looks like.”

Several youth noted that the vaccine incentive system felt coercive and often augmented their skepticism about the vaccine:

– “Why are there incentives on it?”

– “Sorry, but if you give me money for something, that makes me skeptical on wanting to get it.”

– “I mean, if you’re paying me, is there something wrong with it?”

– “Why are they paying us to get the vaccine?”

Access to reliable health information

Young people were often stretched in many ways as they consumed opposing information, which impacted their perspectives on the COVID-19 vaccine. Youth noted that their information sources included word of mouth, anecdotal stories, social media, other online platforms, school, information in public spaces, and information from trusted people in their life. Many youth reported confusion about not knowing which information to trust, particularly as the COVID-19 pandemic continued to evolve. For example, one youth noted, “I don’t know, some people believe that the vaccine could be the virus, some people believe the vaccine could help you and protect you from it.”

As one youth noted, misinformation and lack of reputable sources was a problematic influence for young people: “Unless they cite their sources, unfortunately. It’s just– people can say whatever they want and people believe them, unfortunately. And it’s a problem.” Many staff echoed concerns regarding the inconsistent information being circulated to YEH. A staff member reflected on having a conversation with a young person who worried the vaccine would make her infertile: “They’re not actually pushing facts, they’re pushing fear tactics and so let’s talk about what that really means. And now she knows it’s not the truth, but where you’re getting your information from really matters and just having that conversation, really matters.” The information that youth gathered about the COVID-19 vaccine, coupled with their lived experiences, influenced their decision on whether or not to receive the vaccine.

Youth shared that they received their information from many sources, which we classified as formal and informal. Formal sources were sources that have been classically used to convey health information, including physicians and nurses, parents/family, YEH-serving agencies, libraries, and online or phone-line nurses and clinicians. One youth states, “My family is personally against it, being a Latina female. So, they wouldn’t take it.” Informal sources of health information were sources that youth specifically reported were accessible during pandemic, including anecdotal stories from peers, social media, and celebrity opinions through social media. One staff member said, “A lot of anecdotal trusted people in their lives. Anecdotal stories from a lot of people that are trusted people in their lives. I feel like it has led to a lot of people not getting vaccinated.” Misinformation contributed significantly to the attitudes towards health information for YEH. For example, staff commented on the videos youth would view from TikTok and other social media that disseminated false vaccination information: “The streams of information that is out there, whether it’s on social media, whether it’s in the social sphere, also plays a major influence and a decision they made, whether to or not get the vaccine.”

Basic needs as youth’s priority

Both youth and staff discussed that YEH prioritized basic needs, which often took precedence over receiving the vaccine or seeking information about COVID-19. These unmet basic needs included access to technology, transportation, childcare, and housing (Table 1). Other named conflicts that inhibited youth from accessing basic needs included employment and school time conflicts, interpersonal conflicts, and the hassle factor of planning and following through with vaccination.

While many youth indicated prioritizing basic needs over receiving healthcare or the vaccine, some youth mentioned that getting the vaccine, along with monetary incentives, helped them obtain basic needs. One youth shared, “It’s just scary. You know, I’m homeless, hungry. So, of course I did to get some money in my pocket, get some food in my stomach.” Interestingly, some youth also commented about monetary incentives feeling coercive at times, which could have augmented mistrust of the vaccine (see Historical Harms and Mistrust of Systems above).

YEH’s focus on accessing basic needs was a salient consideration when staff reflected on low youth uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine: “And also understanding that for homeless youth, this is not a priority for them. You know, they’re figuring out where they’re going to live, where they’re going to stay, what they’re going to eat.” Additionally, one staff member commented on several barriers to basic needs that were intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic, which impacted where YEH focused their priorities: “All the barriers still exist… people are experiencing super high rates of mental health issues, not being able to work, poverty, obviously, food insecurity.”

Personal health influence

Several youth commented about how their personal health impacted their decisions to get vaccinated. Pre-existing health conditions, history of allergies, and former vaccine-related side effects were some examples youth reported that impacted their uptake of the vaccine. Concerns about their personal health resulted in worries about receiving the vaccine: “I’ve reacted to just about every other vaccine of other sorts that I’ve taken, so, pretty afraid to take this one.” Conversely, some youth indicated an interest in vaccination as a way to protect their personal health: “A reason to take the vaccine, like, to ensure safety or just wanna make sure that they’re okay.” Staff indicated that many youth felt that the consequences of COVID-19 infection were not relevant to them, as they considered themselves young and generally healthy: “I would have to go back to how much they are aware of the severity of COVID. I think the general perception is that they’re young and they’ll be fine.”

Barriers to healthcare

Youth indicated barriers to accessing healthcare, such as the belief that the vaccine process requires insurance, costs money, or requests personal documentation, such as citizenship documentation or proof of address, which influenced their decisions about COVID-19 vaccination. Concurrently, for YEH, obtaining and maintaining identification may be a barrier in itself, contributing to perceptions of what health and social services they may and may not be able to access. Unclear messaging about what was required was noted as confusing and stressful for some youth considering the vaccine: “For me, it was specifically insurance. Because they’re like, ‘It’s free with most insurance!’ So that means you have to have your insurance all sorted out and have the right one.” Conversely, youth also reported that if they were certain that the vaccine would be free to them and not require any form of insurance, identification, or documentation, then this would positively influence their decision about vaccination. Staff even noted the importance of youth having a trusted primary care provider that youth can rely on for trusted vaccine information and administration: “A lot of them don’t have a regular doctor that they trust.”

Fear or uncertainty of vaccine

Several youth commented on their fears or uncertainties specifically related to receiving the COVID-19 vaccine, which influenced their confidence and uptake. Youth frequently reported fear of vaccine side effects, fear of vaccine composition and development, and fear of needles. Youth reported significant worries about both the long-term and short-term side effects from the COVID-19 vaccine, some of which was misinformation specific to the COVID-19 vaccine that they heard through various channels:

“I have seen many different crazy side effects: deformities, people coming out and not being able to speak, some people coming out being paralyzed, all different side effects that’s unique to different people… And just that kind of uncertainty makes it even less likely for me to even think about getting it.”

Staff often remembered youth worrying about vaccine side effects. Some staff mentioned that youth have voiced concerns about fertility-related vaccine side effects, noting: “That’s something that I think some youth have brought up. They worry about fertility.”

Several youth also noted that their fear of needles influenced their decision about COVID-19 vaccination. One youth commented, “That’s the main part where the needle bothers me because it’s going into a muscle. Like that’s, ouch, because of the longer-lasting pain with that needle versus other needles.” Fear, particularly in the context of youth-directed vaccine messaging, was also highlighted. For example, one staff member explained, “So a lot of the concerns, paranoia, the aversion to the vaccine is stimulated not so much by reasoning, but I would say, it’s on an emotional level. It’s fear.”

Sense of bodily autonomy

Many youth spoke about the importance of bodily autonomy when making their own decisions about COVID-19 vaccination. Youth expressed desire to be in control of what happens to their own body. When discussing how COVID-19 testing and vaccination specifically affect young people in shelters, one youth reported feeling exploited: “They’re lab rats, to be honest.” Another youth similarly indicated how being in shelter can specifically affect their sense of autonomy: “Most homeless youth shelters probably want you to get the vaccine or either get tested every week or every two weeks, I think. So, by them not really having a choice of living, the agenda would be pushed more on them since, you know, it’s more of a public space than inside your own home.” The staff were similarly mindful of young people’s desire for bodily autonomy: “If you feel like you’re being really pushed or coaxed into something, you have that reaction to push back. Just to say, it’s okay to have hesitancy. It’s okay to really think through this, and honor and give space for that.”

Community influence

Young people’s relationships with others, both on an individual and community level, was a factor for many youth when deciding to get vaccinated. Protecting their loved ones or protecting their community by getting vaccinated was important to several youth: “People might want to be vaccinated to protect people around them or their loved ones. People might want to be vaccinated to ensure their safety, make sure that they’re okay.” Community was also noted to be incredibly important for YEH, which includes protecting their community by limiting the spread of COVID-19 through vaccination, as well as youth being able to attend school or community recreational events through proof of vaccination. Staff also report this multi-factorial element of community influence: “I’ve had a good number of young people who were in full support of getting vaccinated… as a way to protect themselves and their loved ones and one step to returning to a ‘new normal,’ if you may, just to be able to do things that they once enjoyed.”

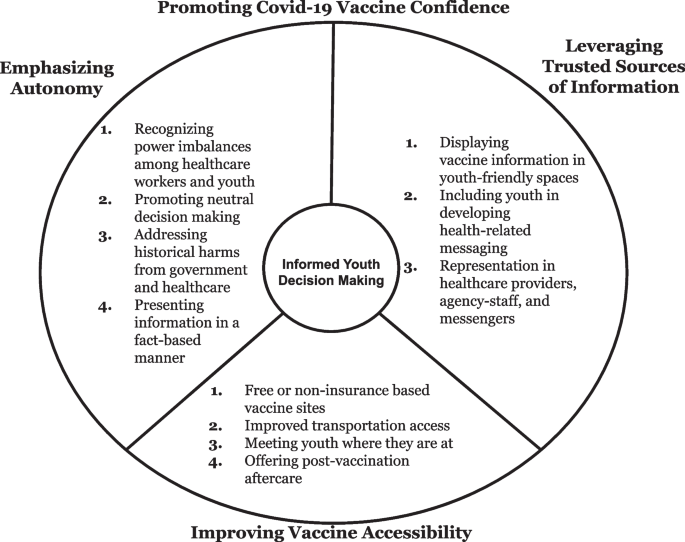

Opportunities to promote COVID-19 vaccination among youth experiencing homelessness

When asked about ways to support YEH interested in learning more about or receiving the COVID-19 vaccine, youth advocated for strategies that could improve vaccine messaging and outreach. These youth-driven opportunities to promote COVID-19 vaccine confidence and access included: 1. promoting autonomy and agency, 2. utilizing trusted sources of information, and 3. improving vaccine access (Fig. 2).

Emphasizing autonomy

Youth reported a desire to have the ability to choose if they receive the COVID-19 vaccine, when and where to get vaccinated, and which type of vaccine to receive. When expressing their hope to be informed about their options and to decide their vaccination status on their own volition, one youth reported: “They just want to have the options. It shouldn’t be – It shouldn’t feel like it’s being pushed.” Many youth commented on their hope to have autonomy in their vaccine decisions, but also to respect the vaccine decisions of others around them. For example, one youth commented, “I gotta see how it’s gonna play out and stuff like that and I didn’t really give my opinion because as time went on, everyone thought of it as political or other things, and I just thought that it’s like a regular flu shot. You can either get it or not get it, it’s your decision.”

Leveraging trusted sources of information

Using trusted spaces to display vaccine information

Youth and staff identified spaces effective at conveying COVID-19 vaccine information and outlined strategies to promote health and vaccine literacy in these spaces. YEH commented that trusted vaccine information should appear on mass transit, a space where agency information is frequently displayed: “You guys are on the buses. That’s why I was like put it by all the [agency] advertisements.” Youth identified several other spaces, as well: “Having information in frequently visited locations such as tobacco stores, liquor stores, the libraries.”

The people conveying COVID-19 vaccine messaging were important to YEH, coupled with familiarity and trust within YEH-serving agencies. One staff member discussed the importance of involving YEH-serving agency staff members in this process. “I think sometimes staff who already have a relationship with young people can be the right messenger. And, yeah, it’s hard, but again I feel like our space is one of the only spaces maybe where they are going to have access to solid information, and we are someone they trust.”

Including youth in developing health-related messaging

When we showed YEH existing COVID-19 vaccine messaging from external sources, they broadly stated the messaging did not resonate with them. When asked their opinions on these videos, youth imagined different ways to present this information to youth: “It would have been better if they had, like, 50 people that were vaccinated and 50 people that were unvaccinated go through these questions…Cause all we looking at right now is statistics and their data that they’re providing us.” Youth also stated the importance of diversity in the people whose experiences were being presented: “I feel like they should have had teens and elderly people and young adults. Like, they can say what their different side effects were or something like that, or how it worked for them. And people with different races.” One staff member identified YEH as being the best source of vaccine information for other YEH. “Getting other young people to join with other scientists or doctors and those young people maybe being trained in and educated about the vaccine…because you have to have that relatable aspect there…”.

Representation and trusted COVID-19 information sources

When YEH were asked about strategies to disseminate information to other YEH, one youth suggested that a phone line staffed by YEH would better equip YEH to make informed vaccination decisions. “I say a youth line. A youth line answered by youth.”

YEH and staff discussed the existing lack of representation in health information messengers and the importance of messaging from people with shared experiences and identities, including racial identity. A staff member noted:

“Well, for sure I think for our youth, it’s really important to see people who look like them sharing the message. Because, maybe this is really blunt, but if you see a bunch of old white doctors talking about it, youth are gonna be like, why should I listen to them? Versus seeing people who are really representational and experts in the field.”

This lack of representation presented concerns about racial representation in vaccine development; for example, one youth mentioned “lack of testing—like the subjects in the trials mostly being white. How can we be sure it’s not gonna affect different people of color differently? And lack of POC doctors, as well.”

A staff member discussed the importance of education in trusted spaces and the burden that falls upon healthcare providers and public health messengers in tackling misinformation.

“It’s really the education component. Our youth are not really getting consistent information and it’s not the right information a lot of the times. So a lot of the barriers are really trying to push out all of the false information that they have to get them to a point of comprehension and comprehending that this is actually going to benefit you and actually going to help you and the people around you.”

Improving vaccine accessibility

By addressing structural barriers, like insurance and transportation, and addressing concerns about managing short-term vaccine side effects, YEH in this study suggested creative, youth-centered strategies to improve vaccine confidence and uptake among YEH. They suggested developing improved vaccine access by addressing structural barriers, which included being clear about not requiring insurance or personal documentation in the future, offering transportation to vaccine sites or bringing the vaccine sites to places where youth already interact, and offering vaccine aftercare for young people. One youth suggested,“I think that if they made the vaccine completely free and not insurance-based or anything else like that, or they had COVID-related vehicles that went to people, such as elderly or youth, or stuff like that. I think that would be a real game changer.” Another youth suggested, “Just COVID information stations and COVID vaccine stations.”; when asked to clarify, they specified, “…You have a section where you can go and read all your information about it and then choose whether you want to stay and get the vaccine or if you want to take some time to think on it.”

Post-vaccine aftercare was also suggested by several youth: “Help them, if they have adverse reactions, like a fever or something the next day, be able to make sure that they can access medication to control the fever, if they’d want to.” A different youth specifically recalled, “When I went to get mine, CVS let me use their chair. They had a designated chair where you had to sit for a period of time after you got your COVID shot. I didn’t really think much of it at the time, but it was helpful.”