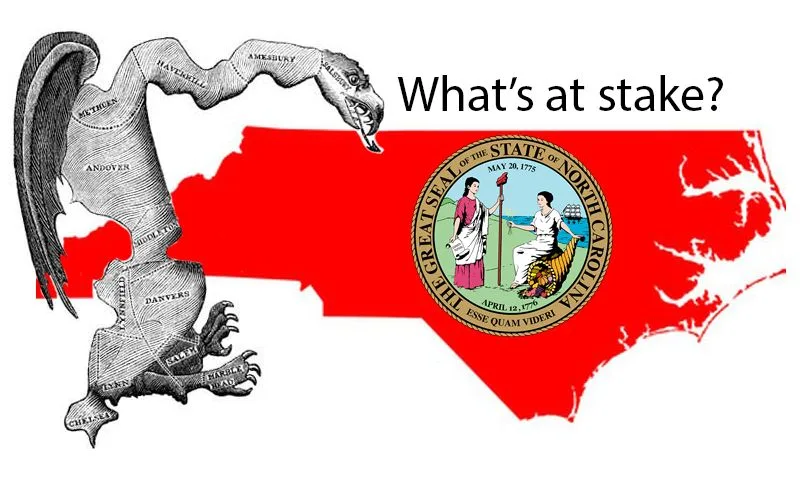

North Carolina’s new voting district maps were hatched in a way that brings to mind Macbeth’s calculation as he ponders murder: “If it were done when ’tis done, then ’twere well / It were done quickly: …”

In other words, it’s a nasty piece of business but if it’ll solve the problem then just get it over with!

Republicans who control the General Assembly figured, as usual, that their problem involved too many voters who might prefer Democratic candidates for Congress and the state House and Senate.

So, after getting the green light from a shockingly compliant state Supreme Court, legislative chiefs this fall redrew congressional and legislative district maps in a process that was rushed, secretive and brazenly Republican-friendly. It wasn’t their first assault on democratic principles, but it was one of their more brutal – “done quickly” with scant public input or accountability.

One could even imagine the perpetrators might have been ashamed, not unlike Macbeth, although that didn’t stop them when they feared their power was at stake.

The Supreme Court, which flipped to Republican control after the 2022 elections, reversed course in deciding that the state constitution couldn’t be read as barring districts drawn to favor members of one political party and to penalize its opponents.

With the path thus cleared for extreme partisan gerrymandering, the legislature approved congressional districts projected to give Republicans at least a 10-4 edge in U.S. House seats in next year’s elections, compared with the current 7-7 split. That’s despite overall vote totals showing approximate parity with Democrats.

Legislative maps to be used in 2024 meanwhile are skewed with the goal of maintaining Republican supermajorities that have rendered a Democratic governor’s veto stamp basically useless.

Even when Gov. Roy Cooper has tried to block Republicans’ cynical “voter integrity” measures aimed at making it harder for Democratic-leaning citizens to cast their ballots, veto overrides have kept voter suppression efforts cranking on all cylinders. Republican legislators like it that way, and no wonder: Checks and balances among co-equal branches of government? How quaint!

Diluted, devalued

If there’s a remedy to these redistricting schemes that are anchored in shameless partisanship, it presumably will have to come via one constitutional voting-rights guarantee that still holds water. That’s the 15th Amendment’s promise that citizens’ right to vote “shall not be denied or abridged” on account of race or color.

Discrimination against Black residents is in fact the charge in a lawsuit now challenging the new state Senate map as being gerrymandered to keep several Eastern North Carolina districts in Republican hands. That would be accomplished by diluting the influence of Black voters and undermining their ability to elect their preferred candidates, who might well be Black and Democratic.

Plaintiffs in the federal case are two African American residents of Halifax and Martin counties, whose attorneys describe how the Black population has been divided among Senate districts in such a way that white majorities are likely to control election outcomes.

Sen. Dan Blue of Raleigh, the Senate’s Democratic leader, issued a statement summarizing the configuration’s harmful effects.

“The plan enacted by the General Assembly in late October splits, cracks, and packs black voters to dilute their votes and blunt their ability to fully participate in the democratic process,” Blue said. “For example, there are eight counties in North Carolina that are majority Black in population, and they are all in eastern North Carolina (Bertie, Hertford, Edgecombe, Northampton, Halifax, Vance, Warren and Washington). The map enacted by the General Assembly divides these eight counties among four separate districts. This is ‘cracking’ on steroids.”

On behalf of plaintiffs Rodney Pierce and Moses Matthews, the lawsuit argues that they could and should have been slotted into a Black-majority district where they’d have a better chance to help elect a Black senator – likely a Democrat as are the Senate’s nine current Black members.

Instead, their counties are included in a district that lumps three majority-black counties together with five that are majority-white, including populous coastal Carteret. It’s a shining example of the gerrymanderer’s art, winding from the vicinity of Norlina near the Virginia border down to Cape Lookout.

The lawsuit first sought a speedy decision on its request for an injunction against the Senate map, which could have led to a delay in the imminent filing period for candidates in the primary elections next March if districts had to be redrawn.

On Nov. 27, U.S. District Judge James C. Dever III denied the request, scoffing at any need for an accelerated court schedule. The injunction request remains alive, but for now candidate filing in districts that arguably muzzle the voices of Black voters will proceed, with a start date of Dec. 4.

Majority rules?

U.S. Supreme Court decisions, stemming largely from past redistricting controversies in North Carolina, have interpreted the 1965 Voting Rights Act as requiring so-called majority-minority districts under certain circumstances.

There has to be a group of minority voters who otherwise wouldn’t have a fair chance to elect candidates of their choice because of a pattern of racially polarized voting that works against them. Other historical factors signaling racial discrimination also come into play. The pending lawsuit asserts that the conditions triggering a Voting Rights Act violation under the Senate map – which fails to provide a single district where Black voters would be in the majority, despite their numbers in the population — have been met.

The plaintiffs’ case might seem rather straightforward, as Sen. Blue’s comments suggest. However, that fails to take into account that federal courts in some instances have yielded to pressures to narrow the scope of the Voting Rights Act.

No longer do redistricting schemes in states with histories of racial discrimination in voting need to be approved by the U.S. Department of Justice. Election rules that negatively affect certain otherwise protected voters can be okay if there was no clear intent to discriminate. Now comes another threat to the law’s application that could, in a worst-case scenario, end up pulling the plug on lawsuits such as the one before Judge Dever.

The threat, in a sense, stems from a provocative comment by Justice Neil Gorsuch as the U.S. Supreme Court in 2021 upheld new voting restrictions in Arizona despite how the Voting Rights Act previously had been interpreted.

Gorsuch, who was echoed by Justice Clarence Thomas, called it an open question whether private parties even had standing to bring lawsuits under the Act, as for decades they have been allowed to do. That amounted to inviting defendants in other voting rights cases to raise that argument and for lower-court judges of a right-wing persuasion to make such a finding. And that’s just what has happened.

Buckle up

First came the ruling of a Donald Trump-appointed federal district judge who dismissed an Arkansas redistricting challenge on grounds that the plaintiffs, including the Arkansas NAACP, lacked standing to sue. The lawsuit had alleged the same kind of Black voting-strength dilution also at issue in the pending North Carolina case. The judge in effect said his hands were tied because the Voting Rights Act didn’t specifically authorize such private-party lawsuits.

Then on Nov. 20 the dismissal was upheld 2-1 by a panel of the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, based in St. Louis. The opinion was written by another judge appointed under Trump and joined by a George W. Bush appointee. The court’s chief judge, also a Bush appointee, dissented.

Now the fun begins. Another federal Court of Appeals, the 5th Circuit based in New Orleans, recently agreed in a Louisiana redistricting case that private plaintiffs indeed can bring Voting Rights Act lawsuits. What this portends is a Supreme Court showdown, with Gorsuch presumably itching for a chance to have the last word.

If aggrieved citizens such as Rodney Pierce and Moses Matthews lose their standing to sue, then it would be up to the U.S. Department of Justice to seek enforcement of the Voting Rights Act’s ban on discrimination against minority voters.

A federal DOJ committed to upholding the right to vote might give that task a good-faith effort, overwhelmed as it was. But let’s not contemplate what likely would happen under an administration that actively wanted to discourage people of color from voting – if for no other reason than they might tend to vote Democratic. Certainly in North Carolina, we’ve gotten a taste of what a nasty business that can be.