A Massachusetts council woman has slammed Boston as the ‘most racist city in the country’ and called for a multimillion dollar reparations package so that black residents can improve their diets with organic food.

Julia Mejia, a Boston councilor-at-large, said the city had only spent $2.1 million to address the ‘historical trauma that’s been carried from generation to generation’ and that much more was needed.

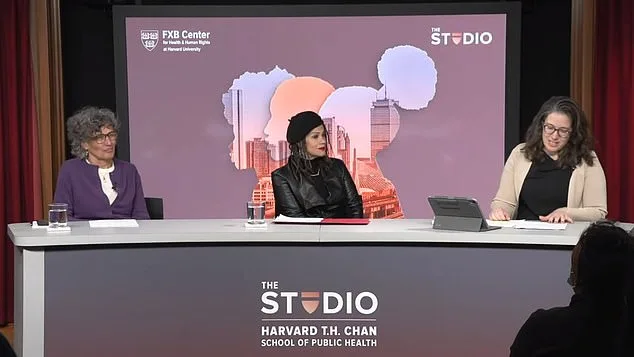

Speaking at Harvard University, Mejia, called for a $300,000 maternity clinic for ‘birthing people’ and payouts, so the descendants of slaves could shop at farmers’ markets for organic syrup and other healthy items.

Reparations activists in Boston seek $15 million to repay black residents for injustices against their slavery-era forefathers — an eye-watering sum that’s nearly four times the city’s annual budget.

Payouts for descendants of slaves are a hot-button issue in America’s culture wars. Reparations are popular among the blacks who stand to benefit, but not for the other groups who would shoulder the extra taxes.

Mejia, an ‘Afro-Latina’ Dominican immigrant who graduated from Mount Ida College, says they’re necessary in Boston because it’s the ‘most racist city in the country.’

She described how black Bostonians had struggled to buy properties, sent their children to ‘under-resourced schools’ and endured ‘underinvestment in black neighborhoods.’

‘The level of racism and segregation and trauma that exists here … has been carried from generation to generation,’ said the Democrat.

The funding that’s been agreed so far — $500,000 to launch the city’s reparations task force and $1.6 million for a commission on black men — was too little, she told the health panel in late March.

She seeks ‘millions of dollars’ in extra spending.

Some of it would tackle the ‘food deserts’ in which black Bostonians lived, she said, where they can only shop at ‘local convenience stores … filled with processed food.’

‘We’re lucky now that we start having farmers markets,’ said Mejia, where products like ‘organic syrup’ were sold.

‘Access to healthy foods also should be part of the conversation,’ she added.

She also called for $300,000 to open a maternity center in the Roxbury neighborhood as a form of reparations to benefit ‘women, or birthing people.’

‘I think we just need to have the political will to move things forward,’ she said

‘I’ve done more in my short time in office than most people who have been there for 20 years. It’s really about the urgency of this moment, and I think that the moment that we fall victim to the narrative of how toxic it is that we’ve lost.’

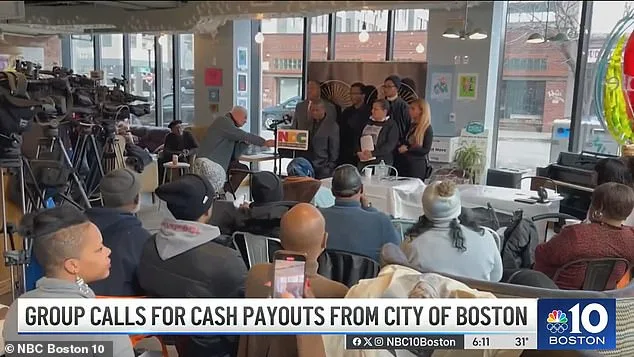

Mejia’s comments come as Boston activists push the city for $15 billion in reparations to black residents, stoking fears of a potential strain on resources amid cuts for cops and veterans in this year’s budget.

Rev Kevin Peterson, of the Boston People’s Reparations Commission, launched the appeal in February, saying the city was ‘built on slavery’ and should now ‘pay back’ black residents.

The sum includes $5 billion in direct cash payments to black Bostonians, a $5 billion investment in new financial institutions and $5 billion to fight crime and improve schools for black kids, the commission says.

Peterson is a leading racial justice activist in Massachusetts, including in the campaign to last year rename Faneuil Hall, a popular tourist site that is named after a wealthy merchant who owned and traded slaves.

Blacks make up about 22.5 percent of Boston’s 651 million-strong population, the US Census Bureau says.

Supporters of reparations say it’s time for America to repay its black residents for the injustices of the historic Transatlantic slave trade, Jim Crow segregation and inequalities that persist to this day.

From there, it gets tricky.

There is no agreed framework for what a scheme would look like. Ideas range from cash payouts to scholarships, land giveaways, business startup loans, housing grants, or statues and street names.

Critics say that payouts to selected black people will inevitably stoke divisions between winners and losers, and raise questions about why American Indians and others don’t get their own handouts.

While popular among black Americans, the other groups who would foot the tax bill are less keen.