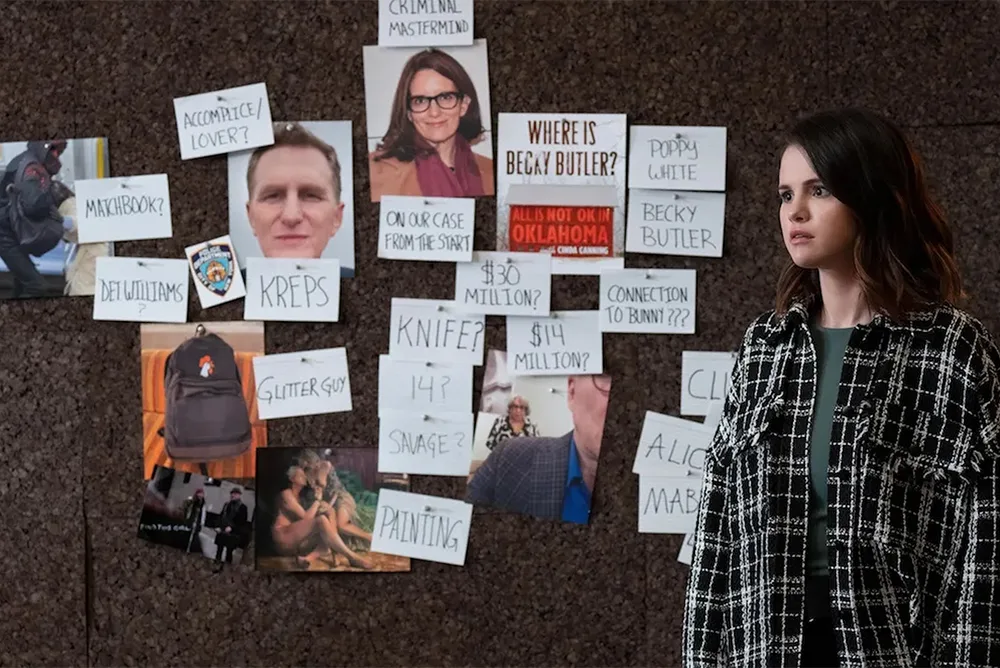

Can true crime be rehabilitated? In search of answers, culture class columnist Jackie Mansky looks to the origins of the genre—and finds a landscape of propaganda and promise. Courtesy of Hulu.

Recreating Mabel Mora’s look for Halloween this year was simple. All it took was a mini skirt, a sweater, some gold hoops, and knitting needles—items I already had lying around my apartment.

Slipping into costume as the youngest member of Only Murders in the Building’s trio of amateur detectives—who, for three seasons now, have been nosing and podcasting their way through the suspicious deaths that keep occurring in their Upper West Side apartment building—is easy, I suspect, by design.

That’s because Mabel Mora (played on the Hulu show by a deadpan Selena Gomez) is meant to personify a face in the crowd—one of countless creators responsible for the very real true-crime boom we’re living through.

Only Murders, like the also-recently-renewed Peacock comedy Based on a True Story, is a self-referential take on a current explosion of amateur sleuths. Nine years ago, journalist Sarah Koenig’s acclaimed investigative podcast Serial arguably launched this era of everyday people attempting to solve hot and cold cases, sharing their findings along the way to an eager public through documentaries, docuseries, podcasts, and more.

That we’ve become so saturated in true crime though should give us pause. As much as I’m a fan of Only Murders, enough to dress up as a character (albeit one I’m dubbing an off-brand SAG-AFTRA-supporting facsimile), the rise of this new meta-commentary subgenre is more proof of how ubiquitous true crime has become. That’s cause for concern. Because for all the promise of true crime, it also propagates dangerous stories that exploit pain for entertainment, and warps the narrative around crime and justice.

How we got here dates back, in part, to victims’ rights efforts that began in the 1970s. In Savage Appetites, the writer Rachel Monroe traces our modern true crime boom to a tangled Frankensteining of feminist rhetoric and tough-on-crime policy that came out of it. Though the victims’ rights movement identified serious failures of the justice system to protect crime victims, in the decades that followed, it went on to push legislation that disproportionally and devastatingly impacted people of color, from mandatory minimum sentencing to “three strikes” laws.

To understand our current moment, though, it’s also instructive to look back even further, to 1800s England, when the first true crime boom launched the popular culture conception of the amateur detective. These early sleuths, notably, emerged out of a climate similar to the one we’re living in today, with a rise of ascendent technologies and media mixed with fear and anxiety around crime, policing, and punishment.

Looking back on the earliest true crime boom is a reminder that from the start the genre has existed in this uneasy paradigm of propaganda and promise.

The 1800s saw radical changes in British society, including the rise of industrialization, which dramatically shifted population centers from rural areas to urban cores. With urbanization came the modernization of law enforcement; the Metropolitan Police Act of 1829 created a standardized police system to replace the existing patchwork network of parish constables and town watchmen. The development of “the new police” was greeted with wariness: Would a centralized system prevent and detect crime, or assert more government control over working-class Londonites?

Alongside the new police force came new ways of gathering evidence. Although ancient forensic practices date as far back as China circa 425 BCE, the 19th century ushered in scientific approaches such as blood analysis, photographic documentation, fingerprint identification, and more. Modern forensics became a point of fascination among the public. They “demanded to know what methods were being used to solve crimes and took an avid interest in how such methods were applied,” scholar Sharon J. Kobritz notes in her research exploring detective fiction as a natural outgrowth of the Victorian period.

A booming press reported on all of this, and the tenor of what was printed varied widely. Some was critical, like Charles Dickens’ early nonfiction work about incarceration. In 1836’s “A Visit to Newgate,” he documented intolerable conditions inside the notorious London prison, which would help inform later fictional works of social criticism like Little Dorrit.

Then there were the endless sensationalist takes emphasizing the gruesome and horrific.

The 1830s invention of the penny press fueled tabloid-like coverage that advanced an unfounded belief that London was experiencing an explosion in violent crime and murder. (Crime rates, in fact, dropped between the 1840s and the 1870s.) In “Common Misperceptions: The Press and Victorian Views of Crime,” historian Christopher A. Casey argues that such perceptions had chilling real-world consequences. From the 1820s into the middle of the century, early crime reformers standardized the system and made it less harsh. But fear-mongering in the press provoked a sharp reversal of course, leading “directly to a re-evaluation of contemporary criminal policy,” Casey writes. Notably, sensationalistic reports helped sink a movement to completely abolish capital punishment, which had previously been gaining steam. (One 1850 petition in favor of ending the death penalty, for instance, received over a million signatures.)

It was the coverage of the police in the press that seems to have birthed the fictional amateur detective we’d recognize in print today. Reporting on law enforcement grew increasingly critical as scandals engulfed its fledgling detective arm in the latter half of the century. Crime fiction scholar Samuel Sanders has made the case that this poor perception of the police in the periodical press “led to the rise of private detectives in periodical detective fiction.” Principal among them: Arthur Conan Doyle’s iconic character Sherlock Holmes, who made his debut in Strand Magazine in 1891. The introduction of the first amateur sleuths at a moment when public trust in the system was low is significant. These characters may have offered a kind of fan fiction for readers disillusioned with the system: a glimpse of alternative paths to justice.

Looking back on the earliest true crime boom is a reminder that from the start the genre has existed in this uneasy paradigm of propaganda and promise. Just as stories shed light on a justice system badly in need of reform, they also played into the fears and anger that propped up that same system of power. But the invention of fictions also offered a space for reimagining crime and punishment.

This feels like one of the most hopeful takeaways for today.

Like many, I started watching Only Murders not for the murders but for the chemistry between Mabel and her fellow true-crime enthusiasts—co-conspirators Oliver Putnam (the soft-eyed, washed-up Broadway producer played by Martin Short) and Charles-Haden Savage (the unlucky-in-love actor portrayed by Steve Martin). But now I’m also watching to see how the show, and others like it, navigate and reckon with our true crime moment.

With one in three Americans saying they consume true crime content once a week, the genre isn’t in danger of losing steam anytime soon. But more self-aware true crime programming that pushes back against the worst tropes could point a way forward and help rehabilitate a genre that’s become all-too-synonymous with advancing harmful and inaccurate narratives about crime, race, class, and gender. That’s important because for all the bad, true crime at its core has the potential to serve as a vessel for change—reminding each of us in the crowd that by being engaged citizens, and championing observation, communication, and critical thinking, we can work together to agitate for a better world.