The second World War was rightly hailed by the victors as a triumph for justice, liberty and democracy. Yet the Allied cause was fraught with embarrassing ironies that included the continued hegemony of European imperialists over half of the world. British, French, Portuguese and Dutch people retained their assumption of cultural and racial superiority. That prejudice often had an underlying religious motif. The Catholic Church, and others, are now dealing with that heritage.

The issue of colonial legacy is being addressed following a growing awareness on the part of victims. In this process, repentance by perpetrators is linked to reparation. Frequently, an apology is not enough. The survivors want compensation for the wrongs they suffered. That is particularly the case in countries which lost large numbers to slavery or to institutional abuse.

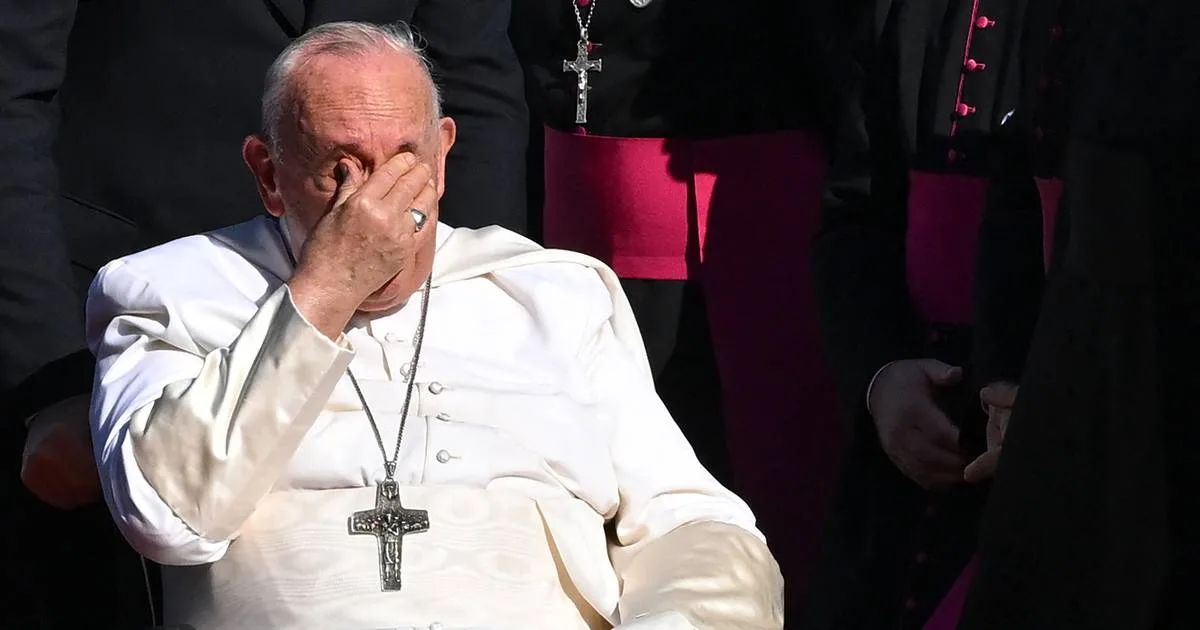

Repentance can take a long time too. The trip to Canada last year by Pope Francis recalled the cultural oppression of indigenous people there. He surprised many observers when he conceded the Church had supported cultural genocide. We now know that between 1870 and 1996, over 150,000 indigenous children were taken from their families there and kept in institutions run mainly by Catholic religious congregations. Those children were beaten for speaking their own language.

Such a frank confession by the Pope was clearly welcomed by relatives of the victims. Moreover, it came soon after a landmark concession by Canada’s prime minister Justin Trudeau. Earlier, his government agreed to pay €963 million to the Blackfoot tribe in reparation for the seizing of their lands at Alberta in 1909.

It is hard for some of us, at this remove, to understand how such a glaring injustice could have been perpetrated by Christians

The remarks by Pope Francis are a reminder of the worldwide destruction of indigenous communities. Slavery was the worst expression of that subjugation, and many of the controversies relate to former parts of the British Empire. That was brought sharply into focus when local people expressed their ire at a British royal visit to the West Indies last year. Local groups staged protests and made loud demands for British expiation. While Prince William recalled the terrible heritage, there were no undertakings given around atonement.

The transatlantic slave trade was among the largest forced migrations in history, and one of the most inhumane. The tide of protest about slavery has crossed the Atlantic Ocean. Ghana’s president Nana Akufo-Addo seeks reparation for Africans damaged by the slave trade. He has argued, based on UN statistics, that 20 million Africans were sold into slavery. He has also claimed that the subject of reparations is selectively discussed when it comes to Africa, noting that the so-called owners of enslaved Africans received reparations when slavery was abolished.

It is hard for some of us, at this remove, to understand how such a glaring injustice could have been perpetrated by Christians.

Like the Canadian government, Australia is committed to making amends for cultural oppression. In the 1920s and ‘30s, the Australian state took thousands of native children from their families. The intention was to assimilate Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders into white society. Campaigners say the trauma of separation has passed down to later generations, contributing to poor health, crime, drugs and abuse. An estimated 33,600 members of the stolen generations survive, with more than 142,000 descendants. The Australian government has promised a €121 million (200 million Australian dollars) reparation package for survivors. Each person would be entitled to compensation, along with a face-to-face apology from a senior government official. Such individual and personal engagement has long held a central place in the Christian tradition.

The question now is whether the Vatican will follow Pope Francis’s admission with compensation for people in Canada and elsewhere

Reparation is being extended to other aspects of colonial depredation. Eco-crime is coming to the fore and it can likewise involve destruction done many decades previously. Shell, the multinational oil company, has agreed to pay the Nigerian Ejama-Ebubu community €80 million over an oil spill that occurred more than 50 years ago in the Niger delta during the 1967-70 Biafran war.

These cases show us that the Pope’s remarks in Canada last year are part of a growing international agenda involving the righting of wrongs by earlier generations.

Over a decade ago Pope Benedict for the sexual abuse of children by priests in Ireland. The 2009 Ryan Commission found that Catholic clergy, over many decades, terrorised children within their institutions. Over 30,000 children were detained in those places and sexual abuse was endemic. In Dáil Éireann, then taoiseach Brian Cowen expressed revulsion at the acts reported by the Ryan Commission and called on religious congregations concerned to make “further substantial contributions by way of reparation”. They agreed to pay a further €353 million – yet, well over a decade later, two-thirds of that remains unpaid.

The question now is whether the Vatican will follow Pope Francis’s admission with compensation for people in Canada and elsewhere. It would be expected as part of the Christian tradition, in which repentance includes reparation.

Dr Diarmuid Ó Gráda is a planning consultant and author of Georgian Dublin: The Forces That Shaped The City (Cork, 2015)