Earlier this month I attended the final ‘Faith in the Story’ conference at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, where I presented some of my work on how Christian privilege pervades and shapes the American public sphere – and why we should work to counter that privilege. Christian privilege in the West is reinforced by what social justice advocate and Jewish community activist Lee Leviter has accurately dubbed “the myth of Christian innocence” – a myth that, as he points out, fuels antisemitism.

Lately, and in connection with the outbreak of violence in Israel and Gaza, I’ve been thinking about how a variety of “myths of innocence” shape both American and global discourse and politics, dehumanising and/or erasing certain perspectives and blocking the pursuit of equality and justice.

America’s foreign policy towards Israel is shaped far more by Christian myths and narratives about the “holy land” and the awaited apocalyptic “second coming” of Jesus than it is by American Jews.

In New York Magazine, Sarah Schulman describes a narrative of innocent victimhood around Israel that elides how the population of modern Israel have “acquired state power and built a highly funded militarized society, and [are] now subordinating others”.

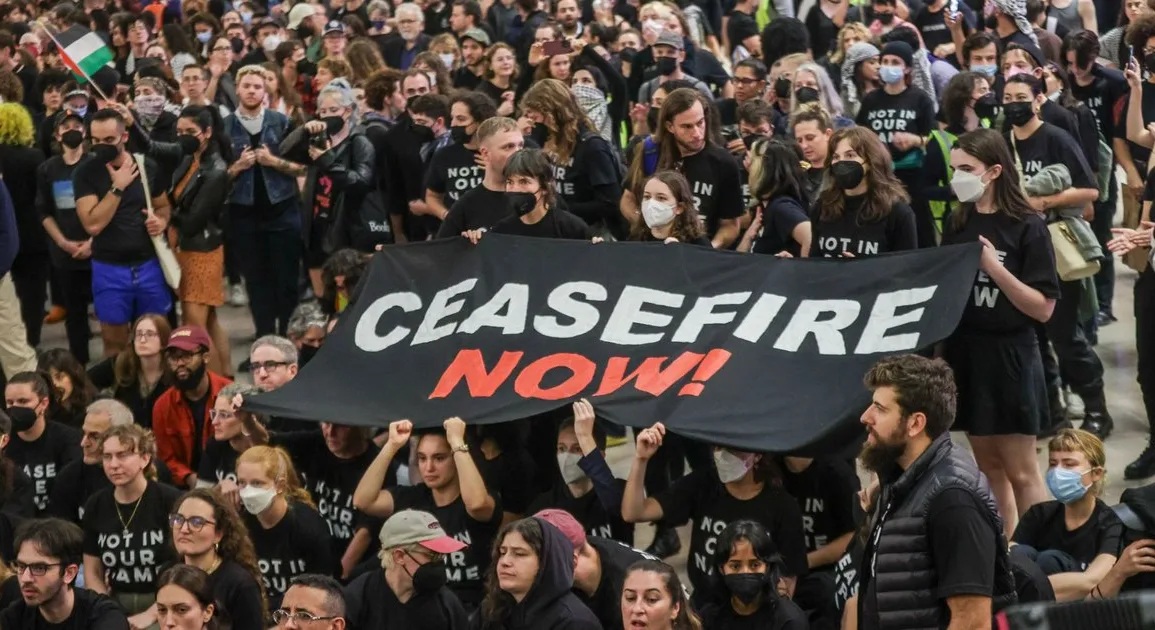

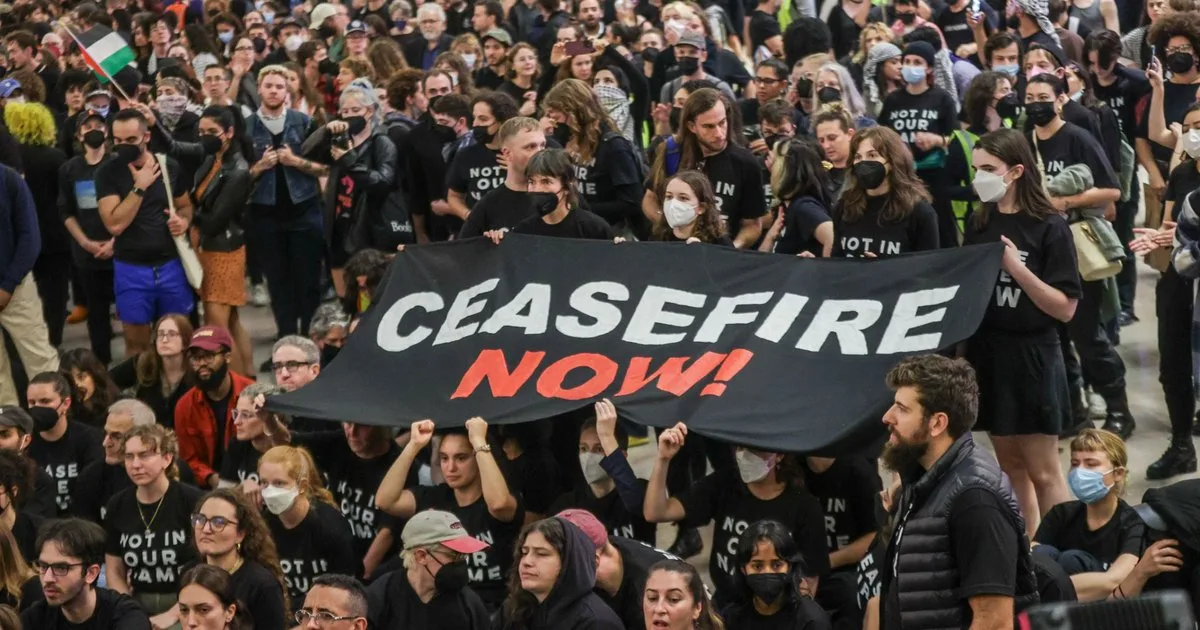

As a result of the manufactured consent around this narrative, says Schulman, Palestinians and their suffering at the hands of an oppressive and often gratuitously violent occupier “become unrepresentable”, and calls for non-violent action for justice along the lines of the BDS (boycott, divest, sanctions) movement are inaccurately and unjustly conflated with antisemitism.

Of course, none of this justifies the brutal actions of Hamas on 7 October. But we must view those actions in context if we hope to work seriously toward a just, stable future for the Jewish, Muslim, and other populations of Israel and Palestine. A black-and-white myth telling us who the “victims” and who the “terrorists” are is an impediment to any diplomatic solution, but the narratives constructed around myths of innocence are hard to shake. “Humans want to be innocent,” Schulman tells us, and further: “Better than innocent is the innocent victim. The innocent victim is eligible for compassion and does not have to carry the burden of self-criticism.”

Myths of innocence are both seductive and dangerous. The myth of the innocence of Benjamin Netanyahu’s Israeli government and military, bolstered by widespread Islamophobia, may be the only one currently present in front-page news, but other myths of innocence play a much larger role in (and beyond) American politics and society than I think many of us would like to admit.

Take, for example, the myth of the “real Americans”, the rural “white working class” folks whom we liberals and leftists just need to find more empathy for, according to the punditocracy’s conventional wisdom. Of course, that is a false solution to a falsely framed problem – the Americans who voted for Donald Trump were not mostly working class – about the racist white Americans who have embraced Trump along with wild, socially destructive conspiracy theories. Disappeared from this narrative are Indigenous Americans and African Americans, but the myth of the rural, white American’s innocence has powerful appeal all the same, even to many American liberals and leftists.

For many white Americans, who may not be too many generations removed from the farm, it seems to me that the myth of rural white innocence is appealing because it preempts the possibility of self-criticism regarding how we have benefited from, and continue to benefit from, systemic injustice. It also helps us to keep the peace with bigoted relatives and to avoid having to think too hard about the overt racism of our forebears.

It seems to me that humans generally do want to be innocent. More broadly, humans – most of us, anyway – want to be good people, and innocence is one measure of goodness. Wanting to be good is not a bad thing. We get into trouble when we allow our desire to be good to become a deep-seated emotional investment in the already achieved status of being a good person, which renders any valid criticism an ego threat.

That individual desire to be good, and to be seen as good, also inevitably becomes wrapped up in our social identities, civic engagement, culture, and institutions, and this has consequences. Myths of innocence that fuel real power in the world exact an unimaginably high human cost – and I mean that more or less literally in the sense that, when state and institutional power mobilises myths that turn human victims into villains, we become less capable of imagining their humanity and their suffering.

On the individual level, it seems to me that the best response to this problem is to cultivate the attitude that goodness is always a work in progress, and never a fully attained status. Collectively, it seems to me that the more aware we become of the power of myths of innocence, and the more we are able to raise awareness in the public sphere by demanding the inclusion of marginalised voices and refusing to accept simplistic narratives, the greater the likelihood we will be able to counter the power of these myths so that context, history, nuance, and multiple perspectives can be heard in the pursuit of both local and global justice.