Illinois city to pay $25,000 in reparations to 140 elderly black residents and has committed to distributing $10 million over the next decade in ‘a test run for the whole country’

- 140, mostly elderly black Evanston residents, will receive $25,000 in reparations

- Chicago committed to $10 million over the next 10 years on local reparations

- Payments can come in either vouchers or cash and are funded by marijuana and real-estate transfer taxes. The program will be a ‘test run for the whole country’

A city in Illinois is expected to pay 140 mostly elderly black residents $25,000 each in reparations by the end of the year in what they’re calling a ‘test run for the whole country.’

In 2019, Evanston a city of 75,000 north of Chicago, committed to paying $10 million over the next 10 years in local reparations and they’ve started to deliver on that promise nearly four years later.

First approved in March of 2021, the program will benefit black residents if they, or their ancestors, lived in the city between 1919 and 1969 or if they can show they suffered housing discrimination due to the city’s policies.

It comes as black communities across the U.S. rallied to help compensate for the legacy of slavery and discrimination they believe has become entrenched within society.

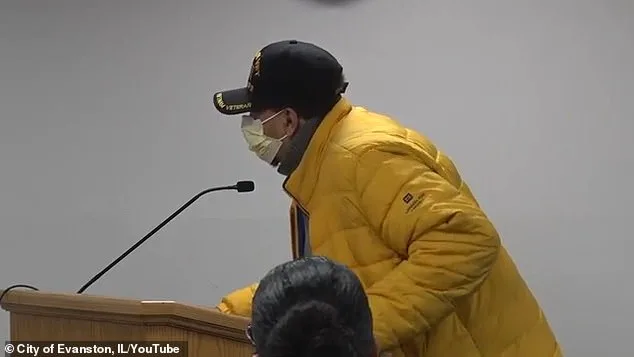

Speaking to the Wall Street Journal Louis Weathers – a recipient of the $25,000 – recalled the first experience he faced with racial prejudice.

The 88-year-old retired postal worker and Korean War veteran claimed the white teacher at his integrated junior high school would make it difficult for black students to show up their white peers.

‘Every time we raised our hand, she wouldn’t call on us, but when we didn’t raise our hands, she would—to make you look like a dummy,’ Weathers said.

‘We got onto that, though. When we didn’t know the answer, we raised our hands.’

Weathers will be among the first to benefit from the program which seeks to pay residents for discrimination and housing – but also works to address gaps in education and economic development.

The payments come in either vouchers or cash and are funded by marijuana and real-estate transfer taxes and is expected to lead the country, according to supporters.

‘I see it as like a test run for the whole country,’ Justin Hansford, a leading advocate for reparations at the federal and local level and head of the Thurgood Marshall Civil Rights Center at Howard University told the outlet.

Apart from his time in junior high, Weathers claims he was discriminated in many aspects of his life.

He recalls being excluded from the YMCA, living most his life in the historically black fifth ward – only being allowed to move to a predominantly white neighborhood in 1969 when the laws changed.

And when hoping to purchase a home in a white neighborhood being forced to threaten a complaint to the real-estate board if the agent didn’t allow him to purchase the home.

Weathers said that he gave his $25,000 to his son, who put it towards debt reduction and upgrades to his condo.

Last month, a task force in California recommended spending billions on reparations as proposals for the rest of the country sit idle.

Meanwhile, a federal bill introduced every year since 1989 that would establish a similar task force at the national level has never been voted on in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Evanston Mayor Daniel Biss told the Wall Street Journal that this hasn’t affected the city’s momentum on the issue.

‘Our job here is just to move forward and to continue being that example, to continue illustrating that a small municipality can make real tangible progress,’ he said.

Robin Simmons, the then-city council member representing the black fifth ward paved the road to reparations.

The fifth ward has historically faced challenges concerning distribution of resources in the City of Evanston, according to the city’s website.

A majority of the population within the fifth ward identify as people of color, while 12 percent of the population of the city is black.

Simmons mostly considered reparations a national issue dealing directly with slavery but later realized local policies such as zoning undermined predominantly black neighborhoods like the fifth ward.

‘We’ve done all forms of affirmative action and equity work that has been really good, but we have not repaired the past harm by the municipal government,’ she told the publication.

In November 2019, the city passed its plan to spend $10 million on reparations with more than 670 residents having applied.

In 2021, 16 people were chosen at random with the use of a bingo cage but it remains unclear when the first payments were made.

Siblings, Kenneth Wideman, 77, and Shelia Wideman, 75, were among the 16 – but while others received their reparations in a timely manner, the Widemans were somewhat left in the lurch – due to program architects’ decision to forgo direct payouts in lieu of grants to address diminished black homeownership at the time.

Since the siblings didn’t own any property, they did not qualify for two of three of the repayment options – to use the $25,000 either on mortgage payments, or home repairs.

The third option was a down payment for a new home – a choice the siblings flouted in favor of cash.

For months, they besieged members of the committee and city to reconsider their stipulations, leading them to toss them in May.

Evanston voted to allow the siblings to get cash payments of $25,000, making them the first in the US to receive direct money.

Wideman told the Wall Street Journal ‘we have not received real reparations, the 40 acres and a mule’ that were promised after the Civil War.

‘I wish people behind me would get that and more than what I got.’

Simmons said the new cash option has reduced the amount of staff work need to disburse the funds.

It has however questioned the affect it may have on recipients ability for other aid programs – an issue the committee are currently working through.

The committee is currently in the process of verifying more than 500 direct descendants of the initial 140 recipients.

Ramona Burton, 74, said she would use her $25,000 voucher for new windows, a new roof, chimney repairs and an updated electric system for her home.

‘I think it’s a good start,’ she said of Evanston’s program. ‘It’s better than a blank.’

Federal reparations efforts have stalled for decades, but cities, counties, school districts and universities have taken up the cause.

An advisory group in San Francisco recommended that qualifying black adults receive a $5 million lump-sum, guaranteed annual income of at least $97,000 and personal debt forgiveness.

San Francisco supervisors are supposed to take up the proposals later this year. But it is currently battling a separate set of problems, including an exodus of businesses in the downtown area amid crime, homelessness and drug abuse.

New York may soon follow in California by creating a commission to examine the state’s involvement in slavery and consider addressing present-day economic and educational disparities experienced by black people.

In California, the state’s Reparations Task Force – which released its 1,100-page final report and recommendations to the public on 29 June – and a University of California, Los Angeles study found that roughly two-thirds of Californians are in favor of some form of reparations, though residents are divided on what they should be.

Roughly two-thirds of Americans oppose the idea of reparations, according to 2021 polling from the University of Massachusetts.

The Pew Research Center found that more than 80 percent of black respondents support some kind of compensation for the descendants of slaves, while a similar majority of white respondents opposed, 2022 polling found.

Earlier this week, Native American groups joined the call for reparations centuries after hundreds of tribes had land taken from them by ‘land-grab universities and colleges.’

An estimated 10.7 million acres of land was taken from 250 tribes following the signing of the Morrill Act by President Abraham Lincoln in 1862.

This law converted tribal lands into initial sites for land-grant higher education institutions in many states.

Now, as several states and cities consider reparations for black Americans, the movement is serving as the impetus for Native American tribes who also believe they also deserve payment for the stolen land.