SB 1403 was a late addition to the CLBC’s priority package. It had the support of advocates who believed an agency, which would determine eligibility, was necessary to establish a viable reparations program.

“I don’t know of any other effort for reparations that did not come with some kind of new state or some kind of governmental institution that was set up to do all of the things,” said Chris Lodgson, lead organizer with the Coalition for a Just and Equitable California, pointing to the creation of the Office of Redress Administration to identify the Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during World War II and eligible for reparations.

SB 1331, which would have created a fund to implement reparations policies, found the same fate as SB 1403. SB 1050, which would have developed a state process for reviewing claims of racially motivated uses of eminent domain and providing compensation to eligible former property owners, passed without opposition and is awaiting Newsom’s signature. The fate of the bill, which was reliant on SB 1403 passing, is uncertain.

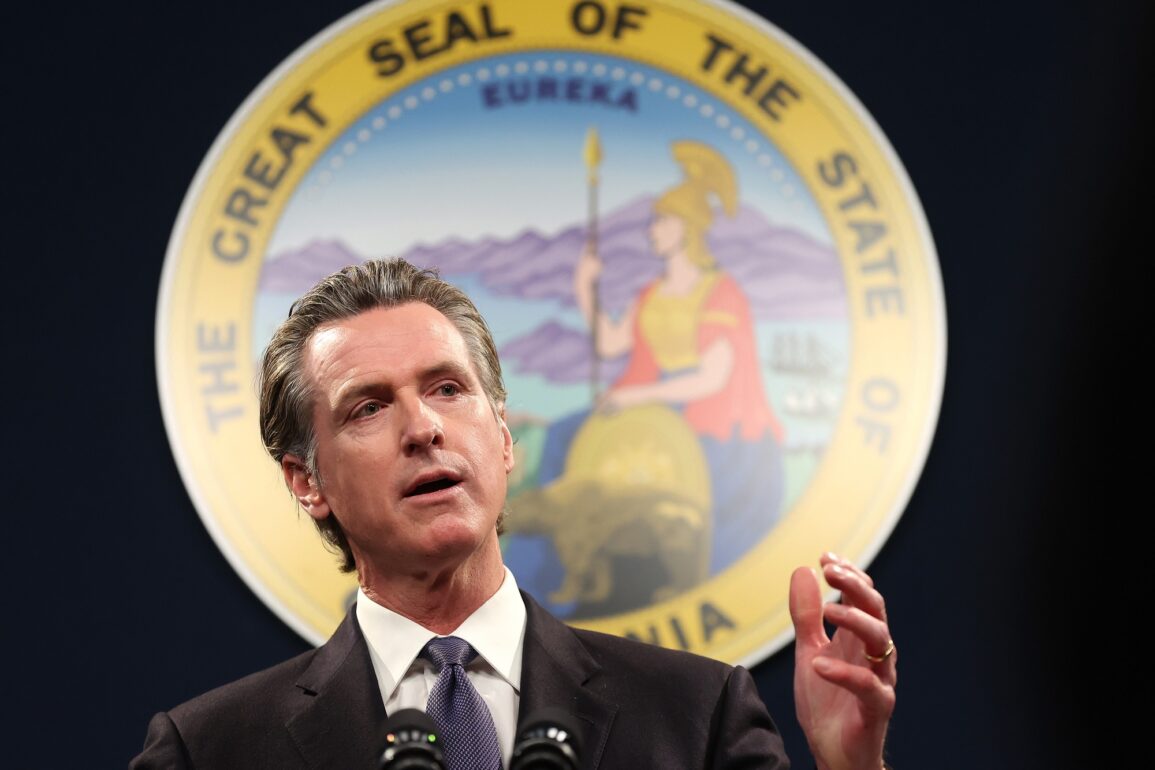

According to Bradford, Newsom was concerned that creating an agency would create a difficult, ongoing financial commitment. California managed to close a roughly $47 billion budget shortfall this year, but according to analysis by the Legislative Analyst’s Office, the General Fund faces a structural deficit in the tens of billions of dollars over the next several fiscal years.

Cost was not the only barrier. Lawmakers in the Democratic-controlled Legislature showed little appetite for measures specifically benefitting Black residents. Bills aimed at targeting state grants toward Black Californians were abandoned, as was a proposal to prioritize Black applicants to state licensing boards.

Changes aimed at state prisons also proved challenging. While voters will have a chance to change prison labor rules in November, a bill to ban solitary confinement did not move forward. And Assembly Bill 1986 would have initially given the Office of the Inspector General the power to reverse book bans in state prisons. The bill now lets the Inspector General publicize the bans and voice disapproval.

“Much like this bill, that [reparations] package was designed to be the first step,” said AB 1986’s author Assemblymember Isaac Bryan (D-Los Angeles). “We know that reparations, repair for the harm that’s happened across California is going to take many, many years. It didn’t happen overnight and it’s not going to be solved in a single legislative session.”

Attention now turns to Newsom, who has to sign or veto the nine reparations bills on his desk before Sept. 30.

Newsom signed the bill creating the reparations task force in 2020, and has spoken supportively of the CLBC’s early efforts to turn task force recommendations into the law. Earlier this year, he set aside $12 million in the budget for reparations programs, though the money is currently not designated for any specific fund or program.

“I haven’t read [the Reparations report] — I’ve devoured it,” Newsom said during his Jan. 10 state budget proposal presentation. “I’ve analyzed it. I’ve stress tested [the ideas] against things we’ve done, things we’re doing, things that we’d like to do but can’t do because of constitutional constraints. And I’ve been working closely with the Black Caucus.”

Dr. Marcus Anthony Hunter, a UCLA professor of African American studies and sociology, said Newsom’s continued engagement will be a crucial factor in determining the success of reparations efforts in California moving forward.

“He could have disengaged at the very beginning,” Hunter said. “So now we’re in it to see: How far is he willing to go?”

Hunter said he’ll be watching to see if Newsom uses his national platform and connections with a potential Kamala Harris administration to tout California’s reparations process nationally.

“I would like to see a push by the governor toward as many things that are possible in a package of reparative justice,” he added. “But also for that push to be a national call on the president to join and lock arms in this and see what is possible across the country.”

To reparations advocates, Newsom’s proposal to amend SB 1403 was an indication that his support for reparations had faltered.

According to an analysis by the Government Operations Agency, the agency would cost $3 million to $5 million annually to operate. In a letter sent on Aug. 20 to the Black legislative caucus by CJEC, the group advocated for using some of the $12 million to start the agency. SB 1403 was added to the CLBC’s priority list after the $12 million set aside made the agency financially feasible.

“We felt like at that time, with the early commitment from the governor and the pro tem and the speaker of this house of allocating $12 million to reparations, that we could potentially get it across the finish line,” Wilson said.

During the Democratic National Convention, Bradford said he began to hear that the Newsom administration had concerns about the cost of a reparations agency.

On Aug. 26, Newsom’s staff asked Bradford to pivot. Instead of creating a reparations agency, Newsom’s staff suggested creating a second study, according to Bradford, who will term out of the Legislature this year and is currently running for lieutenant governor. The study would have further researched the task force recommendations and produced a report designing a process to determine eligibility for state reparations programs.

Newsom’s office said he does not comment on proposals in the Legislature.

Bradford, who also authored SB 1331 and SB 1050, rejected Newsom’s amendment request.

“I spent two years of my life studying reparations,” he said. “We didn’t need any more study and it was now time for action. It was now time for implementation,” he said.

Under SB 1403, a genealogy unit within the agency would have established standards for proving eligibility, something the task force recommended. There was concern within the caucus that Newsom might veto SB 1403 if the bill was sent to his desk without the amendments, according to Bradford.

The bill was awaiting a final vote in the Assembly, where Bradford is not a member. It was assigned to Assemblymember Reggie Jones-Sawyer (D-Los Angeles), a CLBC member who served on the state’s reparations task force, to present the bill for a vote.