I first met the New Haven, Connecticut, photographer David Ottenstein in the 1990s, and in the years since, I’ve kept up with his work—in particular, his long-running quest to visually document the decline of Midwestern family farms and the small towns they supported.

Every two or three years, Ottenstein would give a local public presentation of his latest photos from the agricultural heartland: evocative views of tired-looking barns, houses in need of paint, churches whose congregants had died off, gently rolling farmsteads that had been consolidated into huge holdings dependent more on machinery than on human residents. In 2017 Ottenstein’s Midwestern forays culminated in Iowa: Echoes of a Vanishing Landscape, a contemplative book of photos depicting what the anthropologist Jonathan Andelson calls a “landscape of loss.”

But Ottenstein has also headed in a different direction. From 2012 onward, he teamed up with another New Haven photographer, Robert Lisak, and over a 10-year span they captured buildings embodying American self-government at its grandest.

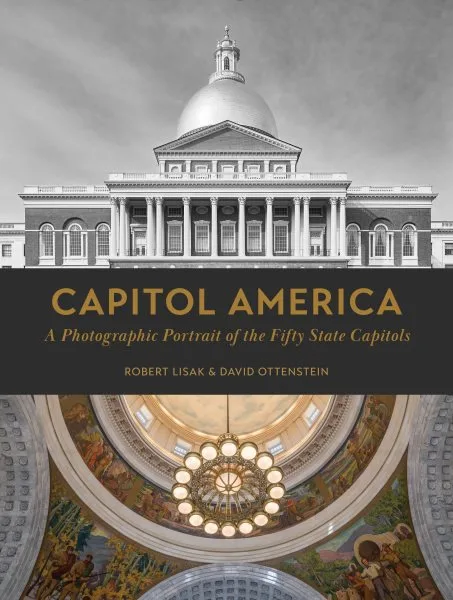

Their new book, Capitol America: A Photographic Portrait of the State Capitols (Schiffer Publishing), shows us buildings that have been, for the most part, diligently preserved, buildings that symbolize high collective aspirations. As if in response to today’s acrid political atmosphere, Capitol America’s 288 oversize pages offer a feeling of reassurance and calm.

Ottenstein and Lisak’s mission drew inspiration from Court House, a sumptuous 1978 book offering essays by six writers—including Phyllis Lambert, Henry-Russell Hitchcock, and Calvin Trillin—and images by 24 photographers who were commissioned to shoot more than a third of the 3,043 courthouses in the 48 contiguous states. Of the thousands of scenes those photographers generated, 348 were presented in the book, many at full-page size. Court House was an enormous undertaking, unsurpassed as a record of America’s county judicial buildings.

Ottenstein and Lisak at first traveled together to shoot capitols in the Northeast and get a sense of whether their ways of working would be compatible. When it turned out that they were, the pair divided the remaining capitols between them and set off on their separate courses.

A few scholars have previously produced deeply researched studies of state capitols. The best narrative history is Temples of Democracy, a hefty 1976 book by Hitchcock, a leading architectural historian, and William Seale, a historian who focused on the White House and other buildings associated with governments. Hitchcock and Seale saw state capitols and skyscrapers as “America’s unique contributions to monumental architecture.” The best book about state capitols from a social perspective—including how the buildings affect political behavior and what kind of impression they make on society—is Charles Goodsell’s thorough American Statehouse (2001).

What sets Capitol America apart from its predecessors is its rich color photography. The book contains a number of black-and-white photos, which do a good job of showing line and form and bringing out the humbler aspects of a building, but it’s the big color photos that are stunning; they explode off the page. The House chamber in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where legislators conduct business beneath Edward Austin Abbey’s towering mural The Apotheosis of Pennsylvania, is an extraordinary sight, crowded with ornament.

That building, an American Renaissance creation by Philadelphia architect Joseph Miller Huston, cost a scandalous $13 million (in 1901–06 currency) to construct and furnish. For lighting, there were gilded electroliers that, according to Hitchcock and Seale, cost roughly $2 million. Some of the huge expense has been blamed on bloated contracts overseen by the state’s Republican machine. No matter. On the day of its dedication, Oct. 4, 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt toured Pennsylvania’s new Capitol and declared it “the handsomest building I ever saw.”

When I was a young reporter at the Harrisburg Patriot-News in the late 1960s, I loved gazing up State Street to the commanding flights of steps, the columned portico, and high green dome of the Capitol. (The dome was Huston’s homage to Michelangelo’s design for St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.) What moved me most was the great building’s placement as the focal point of a downtown street. Years later I would learn that urban designers referred to this as a “terminated/terminating vista.”

Many of the statehouses in Capitol America are well sited. Often they command a hilltop, like the Virginia Capitol, on Shockoe Hill in Richmond, modeled on a Roman temple in Nimes, France, that Thomas Jefferson had admired. Some sit above a body of water, like the Wisconsin Capitol, in Madison, which crowns an isthmus in Madison between Lake Mendota and Lake Monona.

From Ottenstein and Lisak we get rotundas, domes, legislative chambers, statuary, portraits, murals, and much else. “The state capitol buildings,” say the authors, “range in style and feeling from classical elegance, to robber baron ostentation, to practical simplicity, to symbolic modernism, to nondescript office buildings.”

Over time, capitols have changed profoundly. In the first decades of the colonial era, legislative bodies met in ordinary-looking buildings. By the end of the 17th century, however, England decided its seats of power in North America should impress with their stateliness. Toward that end, Virginia’s royal governor, Francis Nicholson, cut a broad street nearly a mile long through woodland and fields to the site of the colony’s second Capitol, in Williamsburg.

Completed in 1703, the “wilderness Capitol of Virginia” was, according to Hitchcock and Seale, “the first building in the New World to take its name from the Capitolium, the ancient Temple of Jupiter overlooking the Roman Forum.” It was “the first monumental structure built to house an American legislature.”

Eventually, a consensus formed about how to compose a capitol. The entrance would be beneath an imposing portico, a “temple front.” From the portico, visitors would proceed to an impressive central space—more often than not, the rotunda. To the left and right of the central building would be two balanced wings, housing the legislature’s upper and lower chambers. A spire or lantern might rise from the capitol’s roof, but in the 19th and early 20th centuries, what was called for was a tall dome.

Contrary to what many might think, statehouse domes were not initially modeled on the U.S. Capitol. In the early 1800s, few Americans were impressed with the muddy, marshy Washington, sited along the Potomac River. Citizens were more likely to visit their state capitol than go to the nation’s capital. The robust federal dome that today serves as a majestic symbol of American democracy wasn’t designed until 1854, by Thomas U. Walter, and it wasn’t completed until a dozen years later. The collection of symbols exhibited by most capitols was rooted in state buildings; between 1783 and 1820, the states energetically erected 17 capitols.

Jacksonians in the West built the first “Greek temple” capitol: Gideon Shryock’s creation in Frankfort, Kentucky, completed in 1830. Hitchcock and Seale observe: “For public architecture, Greek temples had two particularly desirable qualities—they were splendid to look upon, and they could be built to suit nearly any budget.”

Not everything stood up to the weather. The dome of the 1798 Massachusetts State House, an elegant structure by Charles Bulfinch on Beacon Hill, was covered in wood shingles, but they soon leaked. In 1802, the metalsmith and artist Paul Revere was consulted, and the dome was sheathed in copper. Afterward, it was painted for many years, but in 1874 gold leaf was applied, and it has remained gilded ever since.

In the latter half of the 19th century, Greek Revival gave way to other architectural expressions. Money for construction grew. The New York State Capitol, designed predominantly by H.H. Richardson and Leopold Eidlitz, testifies to that. Its Great Western Staircase, with magnificent materials, eye-catching arches, and columns with ornately carved capitals, appeared so extravagant that it was nicknamed the “Million Dollar Staircase.”

By the time the Albany building was completed in 1899, the project had gone on for roughly three decades and was estimated to have cost more than $25 million—“more by far than any preceding US statehouse,” Ottenstein and Lisak report. But, they assert, the Albany Capitol remains “an epic example of American architecture.”

The book’s splendid photos give us much to think about. Why, in some capitols, is there so much grandeur? One purpose may be to “impress upon legislators the magnitude of their task,” writes George Miles, longtime curator of the Yale Collection of Western Americana, in the foreword to Capitol America. “Humble desks sit tightly arrayed beneath spacious, vaulted ceilings, as if the architects set out to remind the legislators that their importance lay in their work, not in themselves.”

A profusion of memorial art in the state capitols reveals what Miles calls “an omnipresent effort to link past to present, sometimes to honor fallen heroes, sometimes to acknowledge difficult truths.” There is an ongoing struggle to achieve the right balance.

The Kansas Capitol, in Topeka, designed by John G. Haskell and begun in 1866, incorporated artworks over the years, but the murals Kansas Pastoral and Tragic Prelude by the Kansas painter John Steuart Curry were rejected—a reaction to Curry’s negative depiction of farming practices that caused soil erosion, and to his seeming celebration of John Brown, who, with a band of abolitionist settlers, killed five pro-slavery settlers in front of their families near Pottawatomie Creek in eastern Kansas in 1856. (That event, the Pottawatomie Massacre, was Brown’s retaliation for a pro-slavery band’s sacking of the antislavery town of Lawrence and for a pro-slavery Southern congressman’s vicious caning of the abolitionist Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner.)

Curry’s murals, made in 1938–40, were not hung when he delivered them. They didn’t go up until after his death in 1946. Finally, in 1992, the legislature apologized for its treatment of the artist and purchased all of the murals’ preparatory drawings.

Whose portraits and whose histories should be valorized in a statehouse? The book shows, in a hallway of the Georgia Capitol, in Atlanta, a painting of Robert E. Lee and, in another part of the building, a portrait of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. It took a while for the portrait of the civil rights leader to be accepted into the building, but now it’s there, conveying a message much different from Lee’s.

In front of the Arkansas Capitol stands a group of bronze sculptures made by John and Cathy Deering and installed in 2005: The Little Rock Nine Monument, a tribute to the nine African American students who began desegregating Little Rock Central High School. The monument faces windows of the office from which, in 1957, Governor Orval Faubus mobilized the National Guard to thwart integration. The Little Rock Nine depiction also stands only a few hundred yards from a memorial to Confederate soldiers.

The same year that the Little Rock Nine monument was dedicated in Arkansas, a bronze figure of Sarah Winnemucca, a 19th century writer, lecturer, and school organizer, was installed in the Nevada Capitol complex, in Carson City. Winnemucca—a Paiute whose birth name, Thocmentony, means “shell flower”—published in 1884 what is considered the first autobiography of a Native American woman. Suffice it to say, Ottenstein and Lisak’s photos reveal the state capitols becoming broader in their art and memorialization.

Gradually, things change, and newer architectural expressions arrive. The Capitol of Florida, completed in 1977, is a slender 22-story Tallahassee tower designed by Edward Durrell Stone in cooperation with Reynolds, Smith, and Hills. Hawaii’s Capitol is a dramatic modern building that sits in a shallow reflecting pool, echoing the state’s Pacific Ocean setting. A central court open to the sky represents what Governor John Burns identified, during the 1969 dedication, as Hawaii’s essence: “the open sea, the open sky, the open doorway, open arms, and open hearts.” Designed by San Francisco–based John Carl Warnecke, in partnership with the Honolulu firm Belt, Lemon and Lo, the Capitol is constructed of concrete and cast stone, and has columns whose tops splay out, a bit like tall palm trees.

The third-newest state capitol, completed in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1966, is low and circular in acknowledgment of Native American influences. Local architect W.C. Kruger found inspiration in a Zia Pueblo symbol: a circle surrounding four equal radiating elements. This configuration, in Zia cosmology, represents a circular sun radiating in four directions, generating four seasons, four ages of life. Thus, four equally spaced entrance wings protrude from the main cylindrical volume. The building is known affectionately as the Roundhouse and is one of only 11 state capitols without a dome.

For all the innovations of recent decades, old capitols with classical-inspired architecture remain prized symbols for their states. Ottenstein and Lisak have assembled a generous, wide-ranging set of photos, evidence of what a government or a people can strive for. In his foreword, George Miles says, “At a time when American politics and governance seem deeply troubled, the images in Capitol America encourage us to ponder rather than to judge, to contemplate rather than pontificate.” He is surely right about that. This is a book that might, if widely distributed, lower the temperature of our politics a degree or two.