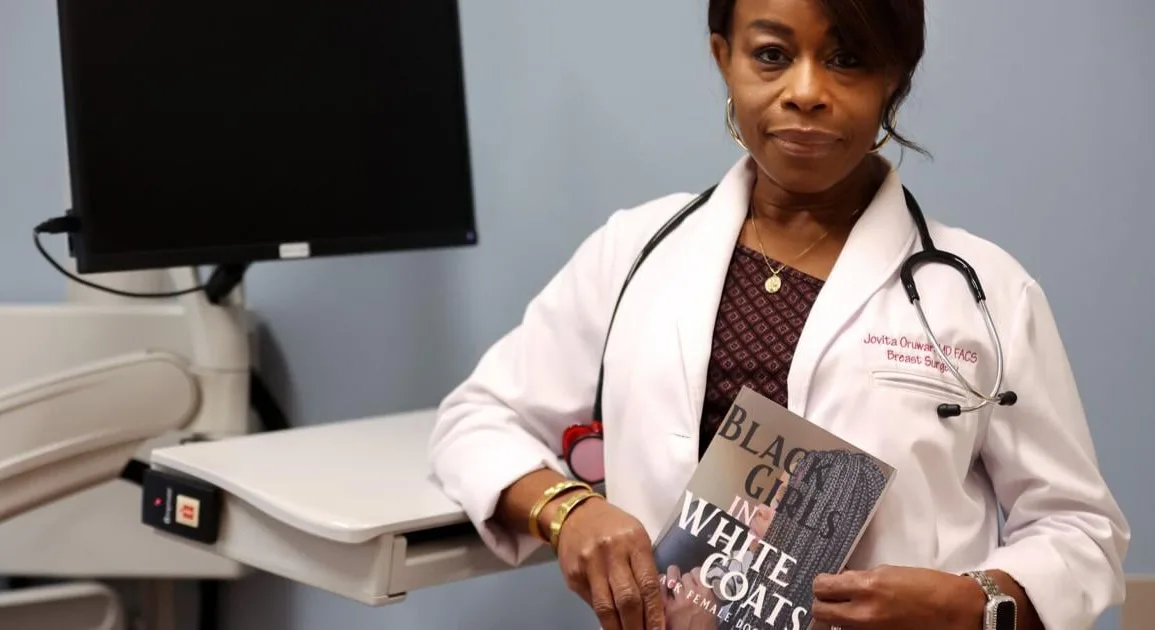

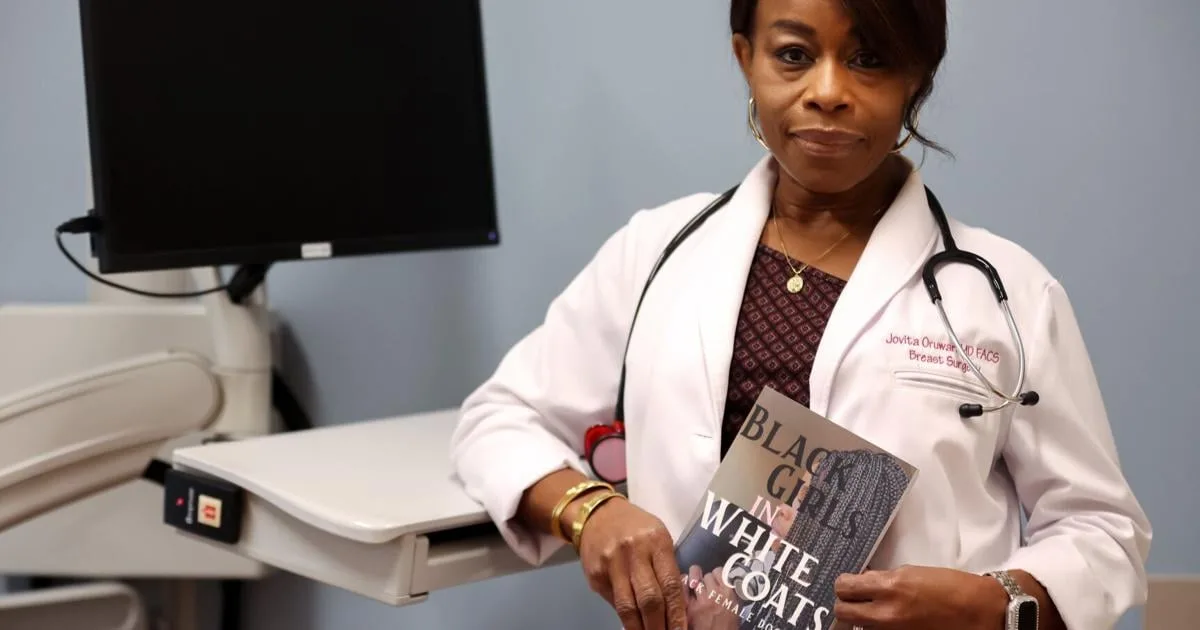

Fewer than 6% of physicians in the U.S. are Black or African American — and even fewer are Black women. Dr. Jovita Oruwari, a St. Louis area breast cancer surgeon, is working to increase those numbers.

In her new book, “Black Girls in White Coats,” Oruwari features a collection of Black female doctors to show the next generation of Black girls that they have a place in the medical field.

“I think it’s really important for us to start thinking about the next generation of doctors,” she said. “There are not enough role models to highlight that this is a great field to go into.”

In the book, medical professionals like anesthesiologists, oncologists and psychologists briefly recount their own career paths and give advice to those aspiring to one day don their own white coats. Oruwari, who is Nigerian, said she hopes the book will help increase the representation of Black women in medicine and ultimately lead to more equitable patient care.

People are also reading…

Dr. Melba Akinwande, owner of Chesterfield Dentistry and a contributor to the book, said her philosophy for building patient trust is about loving the work she does.

“I believe that you give what you have on the inside, and that comes across,” she said. “It comes across in your body language and the way that you greet [patients] with a warm and welcoming smile.”

Akinwande describes in her chapter of “Black Girls in White Coats” that one of her biggest obstacles was believing she could even become a doctor. That was, until she went to her orthodontist — a Black, female orthodontist — for braces at the age of 12. That experience caused her to fall in love with dentistry while also giving her a role model that she said led her to think, “Alright, I can do that.”

She hopes that the book will illustrate that there’s always a chance to become a physician.

“You can still make it,” Akinwande said. “Even if you don’t see it in person, hopefully you can see yourself through the book.”

Building trust with patients

Oruwari said she has seen firsthand mistrust of the medical community, especially among Black and African American patients, which she attributes to the long history of their maltreatment by doctors. During the COVID-19 pandemic, she said, some patients were hesitant to get vaccinated, but she was able to build trust.

“It really highlighted to me the importance of patients hearing things from people who look like them,” Oruwari said. “I think it makes a big difference.”

And she’s not alone in this belief. Studies have shown that Black patients tend to have better population health measures, including life expectancy, when there are more Black primary care doctors in the area.

But that representation is still lacking — despite making up 13.6% of the population, only about 5.7% of doctors in the U.S. are Black or African American, and even fewer are Black women. In the fall of 2022, Washington University reported that just 8% of the degree-seeking students on the medical campus were African American.

After graduating from Rutgers New Jersey Medical School in Newark, Oruwari came to Missouri in late 2001. Now, in Bridgeton, she feels as though she’s found the place where her work can make a serious impact.

“In this demographic, I feel like I’m doing what I was meant to do,” she said. “I think I’m making a big difference because I’m taking care of women who … I don’t think would’ve been cared for or paid attention to as much as I pay attention to them.”

Oruwari sees increasing the representation of Black women in medicine as a path to building more patient trust and correcting disease disparities. For example, Black women still have a 40% higher breast cancer death rate compared to White women, according to the American Cancer Society. These issues put the idea for writing “Black Girls in White Coats” in Oruwari’s mind for years.

During the pandemic, she began to work on the book more seriously and realized that the topic was greater than her own story alone. She started reaching out to other physicians on social media, as well as friends and colleagues, asking them to share their stories.

“It was really heartwarming,” Oruwari said. “Hearing that people had struggles similar to the struggles that I had was great to see.”

Dr. Leslie Scott, an obstetrician-gynecologist also at SSM Health DePaul Hospital and a contributor to “Black Girls in White Coats,” tells in her chapter of the book that she knew she wanted to be a doctor from a young age, and that her experience as a teenage mom led her to choosing a specialty that provides care for women.

“I’m always up for telling my story,” Scott said. “I think that’s what makes my connection with patients and people so much stronger, because I bring myself down to just a person. I’m a doctor, but I’m a person, too, and I’ve had my own health struggles.”

With her patients, she’s noticed that racial concordance can help build trust, but believes that consideration and understanding are more important when it comes to providing quality treatment.

“It’s all about having compassion for where a patient comes from and immersing yourself in their environment and understanding that environment, which really lets them know that you care,” Scott said. “So, it doesn’t really take them looking like you, but it definitely helps.”