On 27 July 1825, a brig called Espadarte (Swordfish) docked in Rio de Janeiro and unloaded its expensive cargo: 422 Africans forcibly shipped across the Atlantic from Angola. It was the first slave shipment known to have been organised by José Bernardino de Sá, then a clerk at a Rio trading house.

Over the following 25 years, undeterred by a law that theoretically made the slave trade illegal in 1831, Sá would be responsible for trafficking at least 19,000 Africans to Brazil – and become one of the empire’s richest men in the process. By the time of his death in 1855, Sá was a viscount who owned countless buildings in Rio, a handful of rural properties on the south-eastern coast, three ships and more shares in the Banco do Brasil than any other individual.

For a long time, the connection between Sá’s fortune, the illegal and lucrative sale of enslaved Africans, and one of Brazil’s biggest and oldest banks was not widely known even among economic historians, because of a normalisation of the 19th-century slave trade, said Thiago Campos Pessoa, whose work helped shed light on Sá’s trafficking activities.

The historian is part of a group of scholars who have extensively researched how slavery shaped Brazil and its institutions, and who are now striving to bring their findings out of academic circles and into the public debate.

Their research prompted prosecutors to launch an unprecedented inquiry into historical links between the slave trade and the Banco do Brasil, which is being asked to propose ways to make reparations.

“This is not an investigation about the past, but about Brazil’s present and future,” said prosecutor Júlio Araújo, who is hoping to spark a society-wide conversation about slavery reparations as part of the fight against racial inequality.

Brazil lags behind other countries such as the US and UK when it comes to recognising how certain institutions and individuals benefited from the horrors of slavery and discussing reparative justice efforts accordingly.

“We want to carry out more research … and reach other institutions, private individuals, to start this debate on reparations, which has never taken place in Brazil,” said Clemente Penna, whose work focuses on how slavery underpinned the credit system in the 19th century. He cites the Caixa Econômica public bank and the Souza Aranha family, who founded Latin America’s largest private bank, Itaú, with a fortune made in coffee, as examples of institutions that could next be pressed to scrutinise their past.

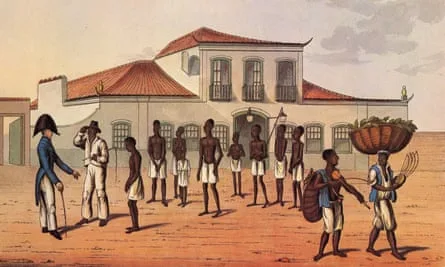

About 5 million enslaved people were shipped to Brazil over four centuries, including 1.2 million after its independence from Portugal in 1822, but discussing how chattel slavery enriched the elite and shaped the nation is difficult because this history was purposely suppressed for decades.

“We only recognised yesterday that racism exists,” said Ynaê Lopes dos Santos, a history professor at the Federal Fluminense University in Rio state.

After the abolition of slavery in 1888, Brazil adopted a policy of collective amnesia that prevailed throughout the 20th century. It is only recently that the majority-Black and mixed-race country faced up to slavery’s enduring legacy of racism and began to embrace its African origins.

Many aspects of the country’s slave-trading past remain silenced, however, like the fact that the sale of enslaved people was illegal after 1831, but continued unrestrained and unpunished with the complicity of the state until a second law was passed in 1850.

after newsletter promotion

“We broadly understand that slavery was a fundamental institution for the organisation of Brazil, but this view usually focuses on the contributions of Africans and their descendants. We forget, deliberately, about the other side of slavery … the enslavers,” said Lopes dos Santos, who helped make the acclaimed Projeto Querino podcast series shedding light on Brazil’s untold Black history.

“It is essential that Brazil recognises its history, how private fortunes, the financial system and a series of other institutions are directly linked with the institution of slavery.”

This side of the story had failed to enter the mainstream because it requires an uncomfortable conversation about white privilege, she argued.

But it is slowly beginning to percolate into public conversation. Shortly after prosecutors announced the Banco do Brasil investigation, three great-great-granddaughters of Domingos Custódio Guimarães, a coffee baron who left his heirs 1,280 enslaved people upon his death in 1868, presented the findings of academic research they commissioned into their family’s slave-owning past on a podcast. They hope to encourage other families to follow suit.

Priscila Fevrier from the Instituto Pretos Novos, a memorial museum located at an old burial site for enslaved Africans who died after disembarking in Rio, believes the timing is propitious politically. “With this Lula government, now we have the ministry for racial equality [re-established this year after being abolished by the previous rightwing government], I think this conversation about reparations is going to take place,” said the doctoral student, wearing Africa-shaped earrings in tribute to her ancestry.

It was under a previous government of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s Workers’ party that racial quotas in public universities were implemented, an affirmative action policy framed as state reparation for the racial discrimination suffered by Afro-descendants in Brazil.

But Alexandre Nadai, who has worked as coordinator of racial equality for the Rio state government, questions how deep commitment to pursuing reparations will run. “True reparation is a question of equality,” he said. “We want to occupy spaces [on an equal footing], but who is going to give up their privileges for that?”