Tucked in the hill country northwest of Knoxville, a short drive from the top-secret Oak Ridge nuclear facility that employed many of its residents, Clinton, Tennessee, in the ‘50s was an unlikely spot for berserk segregationist violence. The Black community was a tiny percentage of its 4,000 population, and the state’s eastern region had an anti-secessionist, pro-Unionist past.

Yet, Clinton was a divided little town. Thanks to the TVA and the Manhattan Project that had made their county the richest in southern Appalachia, the town’s power structure was grateful for the tax dollars and jobs, but some white folks were worried that too much reliance on the federal government might jeopardize their position in the town’s racial hierarchy, what with all this talk about, you know, integration.

Their worst fears were confirmed with Federal Judge Robert Love Taylor’s order to desegregate Clinton High School in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decisions.

Perforce, when 12 African-American teenagers took advantage of Taylor’s ruling and enrolled at Clinton High, they found themselves targets of a spontaneous uprising. Within hours, the situation devolved into a perpetual rampage of locals, further accelerated by a gathering of Dixie’s worst racist factions: White Citizens Councils, the Tennessee Federation for Constitutional Government, the Tennessee White Youth and, of course, the Klan.

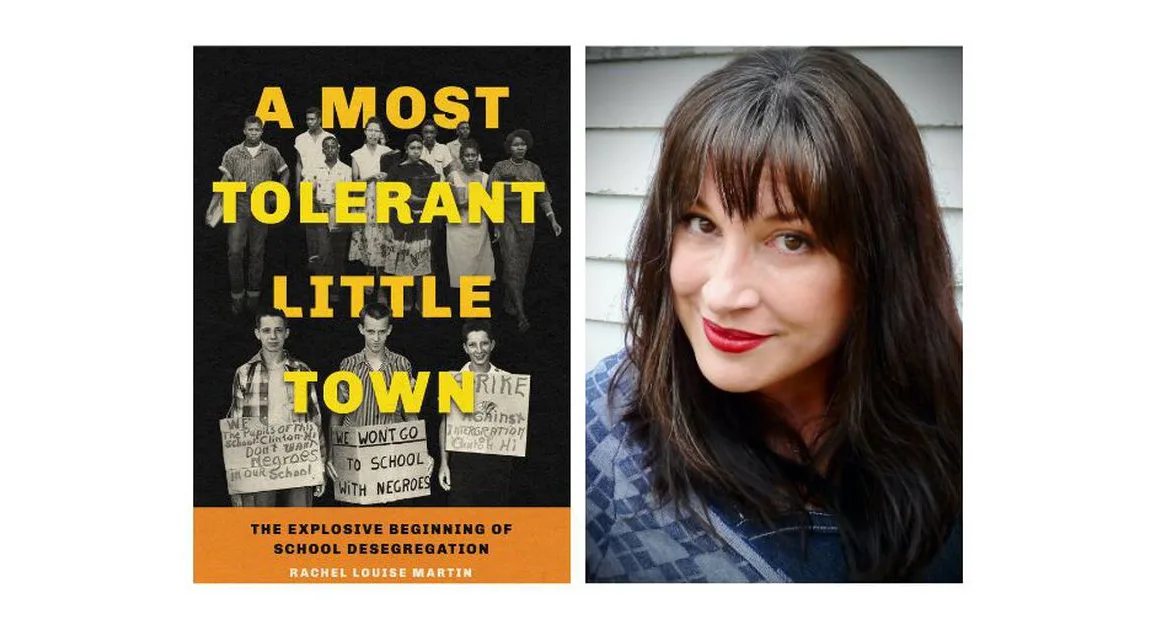

“A Most Tolerant Little Town” is historian Rachel Louise Martin’s exceptional and painstaking reconstruction of the Black students’ experiences during a year of cruelty and humiliation, both on and off campus.

Clinton High School was “…the first instance of court-mandated desegregation in the South.” It preceded the better-known Little Rock disturbances by a full school year and became an extended, international media event.

Yet, when the author begins digging in 2005, she can find almost no mention of the Clinton ordeal on her library’s civil rights shelf. How could such a milestone of the movement, with its attendant global notoriety, be erased from America’s historical record?

“The battle over the story of Clinton’s desegregation is part of an ongoing national struggle over the politics of memory,” answers Martin. “We choose what we want to remember, and we also choose what we will forget.”

Or, as a former Clinton mayor tells the author, “History, if it was a pie, they were taking a bite out of it every year by not talking about it. Eventually, the pie was going to be eat up and no more story.”

In 1956, most of the students — “the Twelve” — lived on Freedman’s Hill, Clinton’s African-American community founded after the Civil War. The events of the 1956-57 school year left many of them scarred for life, reluctant to discuss their memories decades later.

From the first day, when the students marched down the Hill, bottles, rocks, food, and insults were hurled their way. They were confronted with placards scrawled with grotesque racist slogans.

Mass hysteria gripped the townspeople. At a night rally, 800 or more people gathered to hear segregationists speak. “A line of white teenagers snake-danced around the courthouse.”

They beat up a young shoe-shiner. They pummeled Bobby Cain, a black senior at Clinton High. They threatened the school’s “slight and bespectacled” principal, D.J. Brittain Jr., a popular figure who tried to protect the Black students, even though he didn’t believe in desegregation. And so on.

The apathetic police and sheriff’s departments left Freedman’s Hill defenseless. Yahoos cruised the neighborhood, “yelling and threatening.” Black men, several with military experience, formed an ad hoc defense force. Armed with shotguns and whatever else was at hand, they prepared to defend their homes and families.

At the Clinton mayor’s request, Gov. Frank G. Clement deployed the National Guard under the command of Joe Henry, who had a free hand: His nearly 700 soldiers were locked-and-loaded. Submachine guns were mounted in the courthouse and the mayor’s home.

Clinton was an officially occupied town, and calm was momentarily restored.

In due course, the more rabid white supremacists defaulted to their weapon of choice — dynamite — making terror bombing a way of life in the Tennessee hamlet. A bridge, a building, train tracks, the police chief’s house, even a chicken shack, all are bombed or blown up, and if they couldn’t take back Clinton High School for whites only, they’d blow it up, too, by God.

In present day, age comes with the luxury of regret, so why not surrender to the shame? This may be asking too much of a Tennessee White Youth founder, who, when deposed by Martin, snorts: “Honey, there was a lot of ugliness down at the school that year; best we just move on and forget about it.”

Despite the bronze statues that perch like frozen sentries on Freedman’s Hill commemorating the noble determination of the Twelve, a sense of amnesia seems to grip the town.

And thanks to retrograde judicial decrees and pushback of the new Jim Crow, Martin contends that America’s public schools today are more segregated now than they were then.

“When I talk about school integration,” she writes, “I often call it a failure, but what I really mean is that it is an experiment we have yet to try.”

Martin believes that while many of Clinton’s white folks in 1956 may have seen themselves as decent, God-fearing people, “The ugliness of racism had sidelined the other ethical and moral strictures that guided their lives.”

This is one of the strongest, and saddest, lessons of “A Most Tolerant Little Town.”

NONFICTION

“A Most Tolerant Little Town: The Explosive

Beginning of School Desegregation”

by Rachel Louise Martin

Simon & Schuster

384 pages, $29.99