As we left February, which was African American History Month—traditionally referred to as Black History Month—we had Women’s History Month in March. Each month’s purpose is to highlight and celebrate the achievements of each group against the odds of racism, sexism, class exploitation and the remnants of caste ideology of hierarchy and privilege.

What seems peculiar is an emphasis on Martin Luther King during Black History Month and not on the women workers and organizers of civil rights change such as Jo Ann Robinson, Daisy Bates, Fannie Lou Hamer, Diane Nash, Rosa Parks and many others.

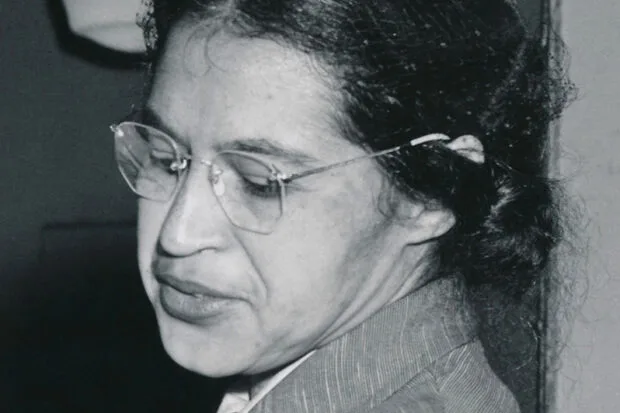

The fact is that King cut his political teeth during the Montgomery Boycott in 1955, as Parks cut her political teeth in 1933 by working with the Communist Party U.S.A. (CPUSA) to free the Scottsboro Boys, all falsely accused of raping two part-time prostitutes who were white women.

It was Parks’ activism on behalf of Recy Taylor and Gertrude Perkins, both victims of rape either by white men as private citizens or white police officers, that led Parks to join the Committee for Equal Justice in 1944.

Parks is on both the political left and a progressive liberal because of her support of trade unionism and workers’ rights as demonstrated by her affiliation with A. Philip Randolph and his Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids. As early as Feb. 14, 1936, with the first meeting of the leftist National Negro Congress, Black women on the left, with many being communist, helped develop a resolution to unionize domestic workers, of which 85% were Black. Park’s progressive liberalism is etched in history books.

Grace Campbell, one of the first Black women to join the CPUSA, observed in 1928 that “Negro women workers are the most abused, exploited and discriminated against of all American workers, not only by the capitalist system…but by the unenlightened race prejudice which is found even within the working class and is used by the employers to drive a wedge between black and white workers and thus destroy their unity and fighting power.”

Campbell was a member of the 1919 African Blood Brotherhood (ABB), which was a socialist cadre of whom many were of West Indian ancestry. The ABB voiced an opposite perspective about the evil of capitalist “democracy” in America than the Black nationalist back-to-Africa perspective of Marcus Garvey.

Later, during the Great Depression, Campbell joined the Harlem Tenants League to combat avaricious landlords evicting renters who were jobless, starving and, like millions of workers at this time, down on their luck and asking anyone, “Brother, can you spare a dime?”

The famous Marxist historian Herbert Aptheker observed of the proletariat castouts, “White workers were starving, but Black workers were starving to death.”

Advocating for the interests of the working class elevated the CPUSA in the eyes of millions, and a united front was built across class lines, in part because the United States was an ally of the Soviet Union in the 1940s as they fought against the evils of Nazism and the militarism of Italy and Japan. Black women “Reds” were in the vanguard of this advocacy.

A famous advocacy case involved, in 1948, the Georgia sharecropper/peasant Rosa Lee Ingram and her sons, who defended her against the attempted rape by a white plantation owner who was killed in the confrontation. It was Black women on the left and liberal civil rights Black women who organized and championed support for the Ingram family.

Urban proletariat women were championed by Black women in the CPUSA. As early as the 1930s, Black women workers accounted for 39% of all women who work.

Leftist Williana Burroughs noted that “in America, the continued search of the bosses for cheap labour has a considerable body of Negro proletarian women.”

Conjoined in these capitalist exploitative social relations is what the future giant of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, liberal leftist Ella Baker, called the “Bronx Slave Market.”

Writing in the NAACP’s news organ, The Crisis, in 1939, Baker said that in an enclave located “at 167th Street and Jerome Avenue and at Simpson and Westchester avenues…a market come rain or shine, cold or hot, Negro women, old and young—sometimes bedraggled, sometimes neatly dressed—waited expectantly for Bronx housewives to buy their strength and energy for an hour” at pennies on the hour.

As one can see, Black politics were eclectic. Living in the “Belly of the Beast,” capitalism, Black women Reds and Black women in left-liberal organizations moved in social activism to “fight to win” against a system of racial oppression. One can readily see this political pragmatism in the life and times of Charlotta Bass, the owner and editor of the progressive left newspaper, the California Eagle.

Bass’s left leaning could be seen when she ran for vice president of the United States in 1952 under the banner of the Progressive Party. Bass also lent her leadership voice in the Los Angeles branch of the Universal Negro Improvement Association founded decades earlier by Garvey.

Bass’s eclectic politics led her to being actively involved in the Los Angeles branch of the NAACP, and she became the national chair of Sojourners for Truth and Justice, an early Black womanist organization.

Another complex but non-contradictory woman was the famous Communist Party member and liberal progressive playwright Lorraine Hansberry. Hansberry wrote the 1959 award-winning play A Raisin in the Sun. The play’s plot revolves around a matriarch in a Harlem high-rise apartment, also known as a “ghetto in the sky,” who inherits enough money from her late husband to move her family to a new suburban home. This move permits her family to move from the inner environs of chocolate city to the vanilla suburbs.

A representative from the all-white enclave arrives at the door of the Black family and offers to buy the home on which the matriarch has put a down payment. The matriarch rejects the offer and decides to move her family to the “burbs” to integrate it or, as in the theme song in the Black sitcom The Jeffersons, the family was “moving on up.”

As an intellectual who embraced the class question, Hansberry, a lesbian and member of the Daughters of Bilitis, moved easily between two ideologies, Marxism and integration.

These two political ideas became the locomotive of social change. The Black Panther Party (BPP), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC/SNICK) embraced these ideas, or the idea of Black Power for the SNCC, and the women members of these organizations believed that one or another other of these ideas would lead to progressive social change for American society.

One such believer in social change was Elaine Brown, who became a powerful voice in the Marxist-Leninist BPP and recorded their theme revolutionary song, “Seize the Time.” Brown became minister of information for the BPP and started the famous Free Breakfast for Children program; upon leaving the BPP, she wrote a tell-all memoir, A Taste of Power: A Black Woman’s Story.

What connects these individual Black women is a bridge encapsulated in the life and times of Molly Moon. Moon was born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1907. She attended the All-Black Meharry Medical School in Nashville and worked as a pharmacist before joining the National Urban League (NUL) and founding the NUL Guild, which became its fundraising arm.

Moon connected with billionaire Winthrop Rockefeller and became a fundraising socialite. Her journey to the left began when she and other “New Negroes” traveled to Russia in 1932 to act in a movie on the Black proletariat in America named Black and White, but the film was never completed. In Russia, Moon witnessed the class progressivism of a Marxist/socialist nation.

As a socialite, Moon bridged the white, wealthy, liberal progressives who helped fund the movement for Black civil rights. Her baton was handed off to far too many for this essay to discuss.

However, let me mention the leadership of Fannie Lou Hamer, who helped found the MFDP during the 1964 “Freedom Summer.” During that summer, hundreds of White students, many of them women from northern college campuses, traveled to Mississippi to register Black peasants to vote. Hamer had been a peasant/sharecropper who picked cotton on a plantation, but she was fired when the plantation owner found out she was an activist.

Hamer led an MFDP delegation to the National Democratic Convention in 1964 in Atlantic City, N.J., to challenge the all-white delegation from Mississippi.

Hamer, in fighting for her party to be the proper multiracial party to be seated and vote for the designated presidential candidate, gave a speech with these words: “Is this America? The land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hook because our lives be threatened daily because we want to live as decent human beings in America.”

Both Black women who joined the Communist Party U.S.A. and Black women who joined the many liberal-left integrationist parties sought to resolve Hamer’s question by their political involvement and activities.