August 30, 2023

1 min read

Source/Disclosures

Published by:

Disclosures:

Shohet reports no relevant financial disclosures. This study was funded by the Social Science Research Council/Wenner-Gren Foundation (grant SSRC-4393), the Boston University Center for Innovation in Social Science faculty research pilot grant and the Boston University INSPIRE (Innovation Stimulus Pilot In Renal) Award. Please see the study for other authors’ relevant financial disclosures.

Key takeaways:

- Disease stigma was a core element of patients’ lives and health care experience.

- Social networks and communities played a role in offering support.

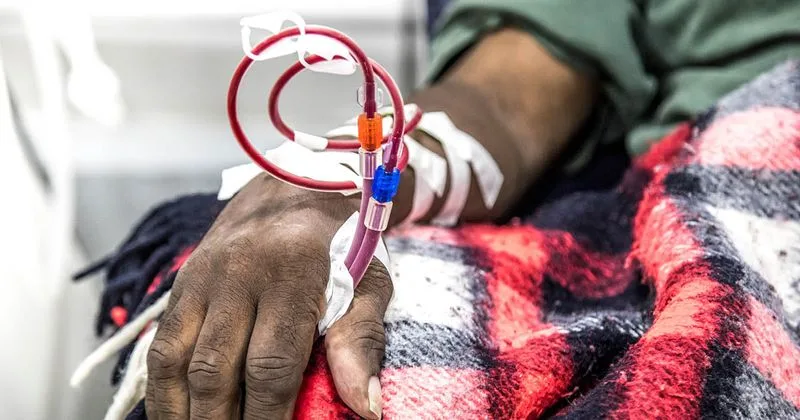

Underrepresented groups with kidney disease face greater health care burdens due to psychological and structural factors, such as stigma and institutional racism, data show.

“Racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States are disproportionately affected by chronic kidney disease and progressive kidney failure, and face significantly more socioeconomic challenges,” Merav Shohet, PhD, of the department of anthropology, Boston University College & Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and colleagues wrote. Researchers studied how these burdens “shape illness experiences and abilities to cope,” comparing findings from before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Researchers of the qualitative trial used purposive sampling to recruit 20 adults on hemodialysis, with most patients self-identifying as Black. Researchers held semi-structured interviews to gather individual patient perspectives about their illness experiences.

“Most patients experienced racial stigmatization and racism,” the authors wrote, including “discrimination in the medical and health care system.” For example, “patients attributed inadequate access to pain relief to medical racism.” A smaller group of patients also reported feeling disrespected and stigmatized due to their socioeconomic status and class.

Three key themes emerged from the research, according to the study:

- Disease stigmatization was a core element of patients’ lives and many participants felt misunderstood due to their illness.

- While the pandemic presented new challenges — patients had to adapt to safety protocols and anxiety about their health — it did not completely disrupt their pre-COVID-19 lives.

- Social networks, including family, friends and religious communities, played a major role in offering patients support.

“Almost all patients mentioned how their kin and friends helped them with daily tasks, such as cleaning, going shopping, bringing food and calling them,” Shohet and colleagues wrote. The results can inform the development of policy interventions to alleviate structural tensions.

“Based on our findings … both a more robust health care system that would guarantee the detection and prevention of the precursors to kidney disease, and more systemic institutional and cultural change are needed to eliminate the ongoing health burdens imposed by overt and covert racism in patients’ daily lives.”