Alexander T. Augusta was turned down for admission to the University of Pennsylvania medical school, a rejection he said was the result of “prejudice against color.”

The year was 1850, and Augusta was Black.

Undeterred, he supported himself and his family as a barber in Camden, earning enough extra income to pay a Penn professor of surgery to give him private medical lessons. Augusta later moved to Toronto to earn a medical degree, earning praise from his teachers, and in 1863, he returned to the U.S. to become the first Black commissioned medical officer in the U.S. Army.

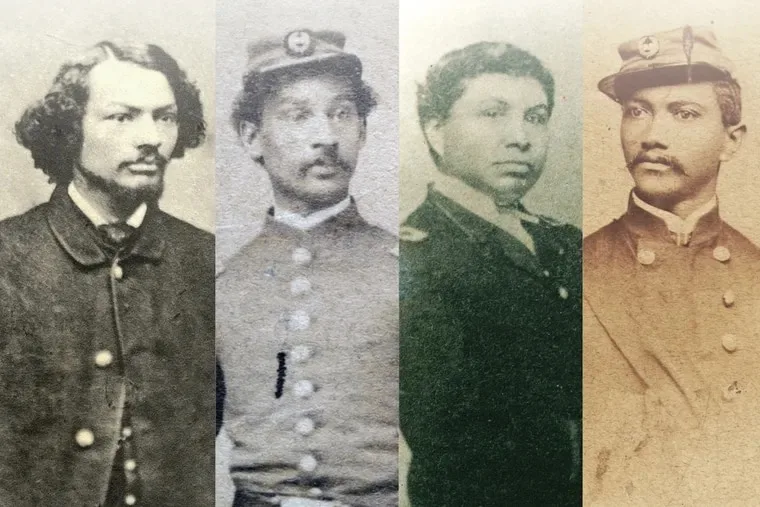

He was one of 14 Black surgeons to serve in the military during the Civil War, treating injured Black servicemen and formerly enslaved people. Their stories are recounted in the new book Without Concealment, Without Compromise: The Courageous Lives of Black Civil War Surgeons (Southern Illinois University Press).

The book has its roots in a 2009 exhibit that author Jill L. Newmark curated for National Library of Medicine. She has spent the years since then searching for more details about the men’s pioneering roles, piecing together clues that were scattered across libraries and archives.

Augusta is one of three with ties to Philadelphia. The others are Charles B. Purvis, son of noted Philadelphia abolitionists Robert Purvis and Harriet Forten Purvis, and William B. Ellis, who practiced medicine in Philadelphia before serving in the army.

The Inquirer spoke with the author about how she wove together the men’s stories, and how in addition to practicing medicine, many of them advocated for social justice.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Why are photographs such a critical part of the story, and how did you find them?

Newmark writes that the sight of Black men in uniform stirred strong emotions: pride in the Black community, gawking coverage from the media, and anger and ridicule from some whites. Augusta in particular drew public attention, as he held the rank of major, his uniform adorned with epaulettes.

“The only way I could tell that story, I needed a photograph of Augusta in a uniform,” she said.

At first, she was able to find only a line drawing of Augusta in the collection of a library in Toronto, where he had gone to medical school. But the drawing looked as if it might have been made from a photograph. Newmark was determined to find the original.

She figured that if anyone had such a photograph, it would’ve been Augusta’s wife, Mary. In her research, the historian discovered that Mary Augusta had come from a devout Catholic family, and that after her husband died, she went to live at a convent in Baltimore where two of her sisters had become nuns. Called the Oblate Sisters of Providence, it was the first religious order of women of color.

Newmark called up the convent on a Friday. She was connected with its archivist, who was indeed able to find the original photo.

“I made an appointment to go on Monday. Of course, I didn’t sleep the whole weekend. Here was this really important photograph. Who would’ve thought it would be in the home of a religious order in Baltimore?”

You write that Charles Purvis was inspired by his parents’ activism to pursue a career in medicine

“Their home [in Byberry] was a stop on the Underground Railroad. They held abolitionist meetings. It was really a center of abolitionist activity. It created an environment of political activism that I think trickled down from the parents to the children.”

During the Civil War, Purvis first served as a nurse at Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington D.C., treating Black civilians and soldiers. He earned his medical degree at what is now Case Western Reserve University, the first Black man to do so, and the Army hired him at Freedmen’s on a contract basis. After the war, he became one of the first Black men on the medical faculty of Howard University and later served on its board of trustees.

Purvis fought for the right of Black surgeons to join an all-white Washington-area medical society, and when he was rejected, he and Augusta established their own racially integrated group. Purvis also successfully sued a Washington restaurant that refused to serve him and other Black patrons. In 1881, he was the first Black physician to treat a sitting U.S. president, as he happened to be in the train station where James Garfield was struck by an assassin’s bullet.

“He and all of these men participated in other types of activities toward abolition and equality,” Newmark said. “It wasn’t just that they served as physicians. All of them expressed a desire to serve their race. They wanted to participate in the fight for freedom in the Civil War. They tried to advance the cause for equality as they provided medical care.”

Describe how William Ellis treated a famous patient and later testified on her behalf

Ellis practiced medicine in Philadelphia before he was hired by the Army to work at Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington. Among his patients there was abolitionist and women’s rights activist Sojourner Truth, who had been assaulted by a streetcar conductor when she tried to board with a white colleague.

“They physically manhandled her and threw her off,” Newmark said.

Ellis testified in the assault case against the conductor, who was found guilty in part because of his testimony, Newmark said. The physician said her injury was due to the conductor’s wrenching her shoulder and not from ”rheumatic affection.”

He was among the first Black physicians to testify in court as a medical expert, helping to break the racist perception that their testimony was not credible, the historian said.