Her writing and her sculpture are motivated by the same relentless urge: to make African Americans aware of their history — and take pride in it

Barbara Chase-Riboud is one of those rare overachievers who are so low-key in the pursuit of their goals that few people recognize the full extent of their accomplishments. The best-selling author is also a sculptor of renown. Multiple careers demand stamina and vision. She has both.

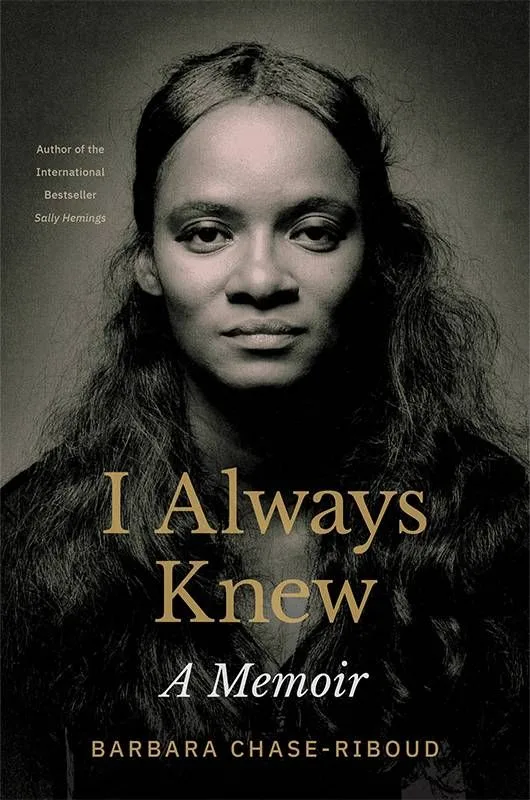

Six novels, three books of poetry, and now a fascinating memoir titled “I Always Knew,” constitute an impressive body of work, but Chase-Riboud has also created enough sculpture to be featured in simultaneous traveling shows. The Museum of Modern Art in New York showcases her work through October with “The Encounter: Barbara Chase-Riboud/Alberto Giacometti.” Her writing and her sculpture are motivated by the same relentless urge — to make African Americans aware of their history and to encourage them to take pride in their heritage.

Multiple careers demand stamina and vision. She has both.

Chase-Riboud lives in an elegant tapestry-hung apartment in Paris with a spectacular view of the Luxembourg Gardens. In the morning, she can be found at the marble desk in her alcove study, cradling a cup of pale Russian breakfast tea. She looks up, having just put down the black fountain pen with which she had been covering page after page of a legal pad with her artistic scrawls.

Next to the desk stands a bookcase jammed with books on architecture, an interest she shares with her Italian husband Sergio Tosi, a prestigious art publisher. The alcove also contains phone, fax, and writing material. It’s here that she draws inspiration, surrounded by portraits of some of the 18th century celebrities who figure in her books.

An Accidental Historian

In 1979, Chase-Riboud wrote a historical novel that turned its author into a celebrity. “Sally Hemings” tells the story — based on conjecture — of Thomas Jefferson’s mistress, a slave and the half-sister of his deceased wife. Chase-Riboud learned of the role Hemings played in our third president’s life from a biography by Fawn Brodie, published five years earlier.

Jefferson’s account books reveal that the future president lavished special attentions on his young slave while serving as American envoy to France. Subsequent DNA testing of their descendants proved him to be the father of Sally’s son Easton. Chase-Riboud spent three years poring over contemporary accounts of the Jeffersonian years prior to offering her own interpretation. Living in Paris made it easy to imagine their relationship. She fleshed out her heroine so completely that this first novel was at times taken as history.

Explaining Sally Hemings became almost a mission. Chase-Riboud is quoted in the New York Times of June 2, 1981, as saying, “The fact that Jefferson is great is not in dispute, and the fact that Sally Hemings is black is not in dispute. But the blending of great and black seems to be what makes people climb the wall. It has to do with American historical attitudes, and it has to do with race. One of the ironies is that Sally Hemings was three-quarters white; she was black because she was defined by her society as being black.”

Chase-Riboud’s new memoir is composed of letters to her mother sent from September 1957 to October 1989. “I Always Knew” reveals the author’s behind-the-scenes emotions before and after the publication of her bestseller. In 1977, she describes what success feels like, calling herself an “accidental” historian: “Nobody said, ‘Be careful because your primary goals and your personality as an artist will be eclipsed for a while and your life will be changed forever.'” In 1983, she proudly reports to Vivian Mae, “‘Sally Hemings’ is now in 25 different editions in 8 different languages with over a million and a half copies sold.” By the end of the century, that number had risen to 3.2 million.

Advertisement

Several Projects at Once

Chase-Riboud has fans all over the world. From her memoir, they can now learn how she came to write “Sally Hemings” and the role Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, her first editor, played in this decision.

After the novel’s publication, Chase-Riboud divided her time between book promotion and sculpture, a skill in which she had been trained at the Yale University School of Design and Architecture. “I Always Knew” records how incredibly busy her life was. Houses, parties, fashion, travel, two children, two husbands are all described affectionately in candid letters to mom.

Only in 1994 was Chase-Riboud able to return to art full time. Her work is characterized by the unexpected combination of hard and soft materials: monumental bronze supported by sturdy silk braids. Individual pieces, such as the “Malcolm X” series, reflect the artist’s concern with African American history but were not created as political statements per se. In an early letter, she asks the question of what qualifies as “black art.” She set out to prove there was no such thing and “the idea that there was, was as stupid as listing rhythm and blues and pop music separately, one for Blacks and one for Whites.”

Extremely productive, Chase-Riboud is always involved in several projects at once. She can be completing a series of drawings and writing a poem in her head while imagining the next chapter of a manuscript. Admirers wonder where she gets such energy and vision. Somehow it all comes together, often in miraculous ways.

She would prefer to be appreciated for her own capabilities, not sequestered, labeled and packaged because of the color of her skin.

Through her first husband, French photojournalist Marc Riboud, Chase-Riboud was given the opportunity to meet a number of prominent people. With her natural charm and grace, she made friends easily. Quick to realize the importance of these contacts, she built bridges to the future.

In her memoir, Chase-Riboud deplores the racial disparities that continue to plague the United States. She would prefer to be appreciated for her own capabilities, not sequestered, labeled and packaged because of the color of her skin. When questioned on what she calls the “obscenity of racism,” she alludes to her two marriages to Europeans and her ease with people of various ethnic groups. That race does not count among her preoccupations, however, would be impossible. Chase-Riboud herself is of mixed ancestry. The importance of skin color is illustrated by this excerpt from “Anna,” an early poem published in “From Memphis and Peking,” edited by Toni Morrison:

You looked at me and murmured,

“Too dark.

She’ll never be beautiful.”

Oh Great-grandmother,

The blood

You let

With that

Offhand remark,

The absolute wound

That saw

My life flow

Out —

Sweet dreams of myself,

Shot free like stars spinning

From another galaxy!

‘My Plate Is Full’

Though Chase-Riboud left the United States initially on a John Hay Whitney Fellowship at the American Academy in Rome, racial tension may have contributed to her decision to remain abroad. Paris is known to be a haven for people of color, who are appreciated for their talents and often encouraged to develop their skills more fully than back home, where racial prejudice can take its toll.

“I can’t imagine moving back,” Chase-Riboud says. Europe has become home. From Rome or Paris, she continues to monitor the politics of race, faithfully applauding each victory of prominent African-Americans, with whom she empathizes from afar.

More important to Chase-Riboud, however, than any award remains her success in introducing the American public to African-American heroes.

2023 is the year her sculpture will gain a wider audience.

“My plate is full,” she adds. “I am preparing a solo booth at Freize London, a group show at the Metropolitan, a traveling show in Essen, Germany, and a solo show at the new Hauser Wirth gallery in New York.”

In 2022, the French government recognized her accomplishments with the Legion of Honor, an award bestowed on Josephine Baker 60 years earlier. More important to Chase-Riboud, however, than any award remains her success in introducing the American public to African American heroes. For years, textbooks presented slavery only from the point of view of the landowner or the abolitionist. Thanks to her fiction and art, African Americans can better appreciate the contribution their ancestors made and take pride in their heritage. And for Barbara Chase-Riboud, that’s what matters.