(RNS) — For Kenya Procter, a pastor who trains other faith leaders to understand and prevent suicide, it was personal before it became her job. Two decades ago, she and her husband, Fallon, lost a close friend named Jay they had gotten to know when the two men were serving at a U.S. Army base together. After Jay’s death, Procter couldn’t stop ruminating over why he had chosen to end his life.

Procter also found she couldn’t comfortably talk about it. But in 2010, a volunteer spot opened up at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention while Fallon was serving at Fort Bragg, now Fort Liberty, in North Carolina. Procter realized she could channel her own response to Jay’s death into helping others who had lost someone to suicide.

“It gave me this ‘aha’ moment,” said Procter, who today is executive pastor of Ambassadors for Christ Worship Center, a nondenominational church in Raeford, North Carolina, where Fallon is pastor. “I wanted other people to know that you don’t have to walk around with this stigma because you lost someone to suicide.”

Raised in the Black church tradition in Louisiana, Procter has learned that part of her discomfort in talking about Jay’s death had to do with her upbringing; as a clergyperson, she knows that Black pastors are among those who most need to talk about suicide.

Today, Procter is part of a national movement that works with community-based organizations, health officials and mental health advocates to train Christian faith leaders on how to talk to their parishes about this critical topic. She is also on a mission to make sure that clergy receive the help they need to come to terms with their own mental health needs.

Suicide has a disproportionate impact on Black communities in the United States: In 2020, suicide was the third leading cause of death for Black people in their teens and early 20s. In 2019, young Black women in particular were 60% more likely to attempt suicide than their white peers.

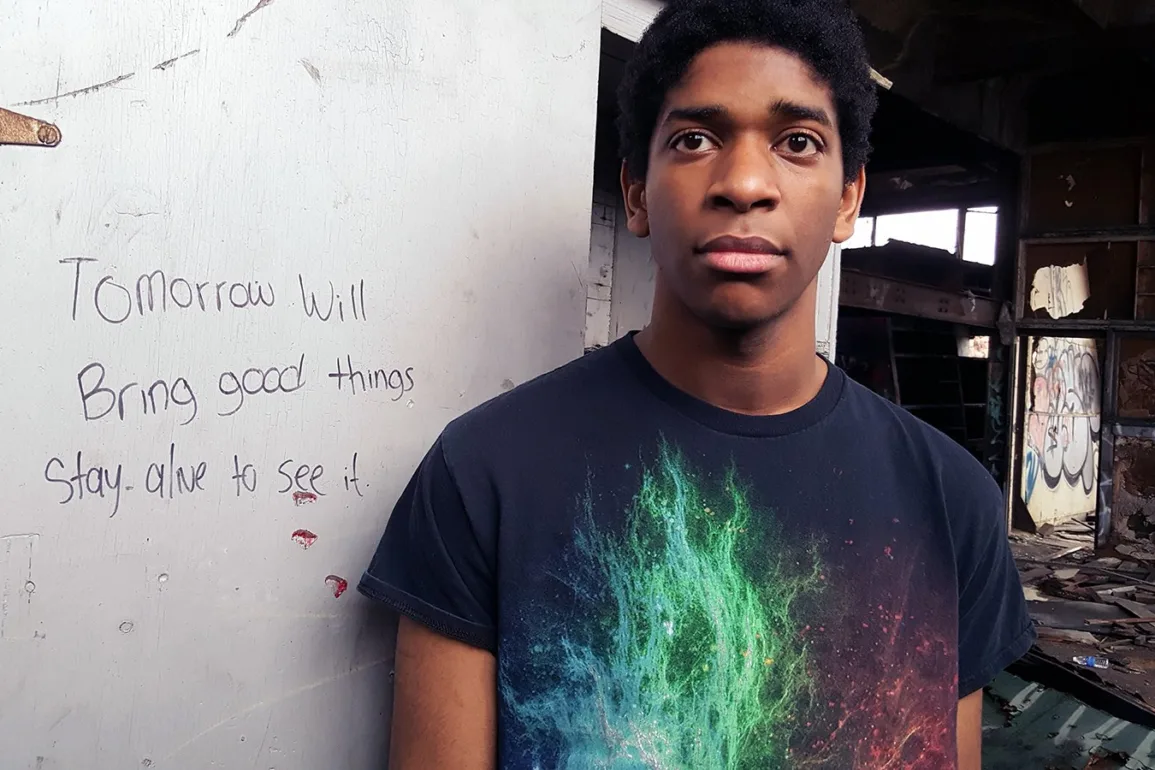

(Photo by Siviwe Kapteyn/Unsplash/Creative Commons)

In many Black communities, the church is often a hub for many services beyond spiritual uplift. In rural communities especially, congregants and noncongregants rely on churches for information about everything from voting to health care. It is also the first place many people bring their celebrations and their troubles, money struggles and personal grief. So if clergy isn’t talking about suicide, “then that means nobody’s talking about it,” Procter said.

Soon after she volunteered to help with suicide prevention at Fort Bragg, Procter joined a program called Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training, known as ASIST, and began teaching others to do the work. As she graduated to a board chair for the program and became a pastor herself, she became more concerned with faith leaders’ views about, and susceptibility to, suicide.

“I had been screaming for years saying, ‘We need to do something for clergy.’ And me being clergy, you would think it would be easier, but it’s not. It’s so hard to get clergy involved, to say, ‘Let’s have a conversation about suicide,’” she said.

Kenya Procter. (Courtesy photo)

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services sponsored a grant program to investigate ways to reduce disparities in delivery of health care. North Carolina’s public health officials took advantage in part by partnering with LivingWorks. The resulting program was called Faith Leaders for Life and focused on suicide prevention. LivingWorks, which is the parent company of ASIST, was asked to develop a training program for clergy. Its director of faith community engagement, Glen Bloomstrom, in turn tapped Procter as one of the faith leaders working with other clergy.

The silence in the Black community about suicide goes beyond faith, Procter said. The history of oppression has made having resilience and mental strength — or at least being perceived to — a necessity for survival. “We don’t talk about mental health, we don’t talk about suicide,” said Procter. “If we’ve lost someone to suicide, we go, ‘The person passed away.’”

The church reflects this taboo about mental illness by classifying suicide as a sin, which is “not helpful,” said Procter, who cites a verse from the Book of Hosea, “My people are destroyed for lack of knowledge.”

As a result, clergy tend to lack training in mental health and suicide prevention. They might also struggle with suicidal thoughts themselves but not know where to turn.

The first step to ending this cycle, Procter said, is to stop clergy from only reacting to mental health problems when they become a crisis. “Pastors are traditionally, historically putting out fires. That’s what we do. But if we can get to a place where we are proactive in things, then maybe it might be smoke and not a fire.”

This may mean knowing crisis intervention training officers in the area, or simply having on hand the number for a suicide crisis hotline or even a resource sheet on suicide prevention and intervention.

A more robust solution is training in suicide prevention through LivingWorks Faith, a program that grew out of longtime work with the U.S. Navy chaplaincy, or Soul Shop for Black Churches, which teaches LivingWorks ASIST techniques in a one-day workshop for Black clergy.

Photo by Claudia Wolff/Unsplash/Creative Commons

“Churches are an important part of many Black communities, a trusted resource, a safe place to go,” said Garra Lloyd-Lester, the coordinator of community and coalition initiatives at the Suicide Prevention Center of New York City’s Office of Mental Health, which also offers New York clergy free access to the LivingWorks Faith programming. “It only makes sense that we have information that’s tailored to those communities, to be able to include how we talk about suicide.”

Soul Shop for Black Churches was inspired by the Rev. Erwin Lee Trollinger, pastor of the Calvary Baptist Church of White Plains, New York, after he became aware of how many clergy he knew struggled with mental health. He connected with leaders at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention who in turn brought Soul Shop, a group founded by Fe Anam Avis, a onetime Ohio pastor who had experienced the loss of three young people in his church to suicide in less than a year. He eventually created a one-day suicide prevention workshop for faith leaders and turned it into a nationwide program.

With Trollinger’s call to action, Soul Shop and AFSP leadership came to the same realization: They needed to adapt the ASIST curriculum for the Black church.

“I said, ‘If you’re going to have the faith community as a target, you’ve got to make sure that the faith leaders are also trainers,’” said Pat White, chair of diversity, equity and inclusion for AFSP’s chapter covering New York’s Hudson Valley and Westchester County, home to Trollinger’s church. White insisted that all the training would take place in churches, with the senior pastor and associate pastor involved.

She also imposed a “deal breaker” threshold — at least 50% of workshop registrants had to be from the congregation of the church where the workshop was being held. “Then they as the congregation will be the messengers for all the work, all that they’re hearing, all the lessons, and then they’ll start talking by just talking,” White said.

Working with these principles, Soul Shop for Black Churches has since grown far beyond New York.

Procter is proud of the progress the cause of mental health has made in the Black church community and among its clergy. Lately, she’s found more hope in the awareness of a younger generation in mental health, including in her own home: After years of hearing the importance of mental health preached at the dinner table, Procter’s 17-year old son, her eldest boy, has recently volunteered to undergo suicide prevention training.

This article was produced as part of the RNS/Interfaith America Religion Journalism Fellowship.